Ashok Ogra

Never has the Congress party been in such bad odour with the people. And never before has the distrust of Congressmen been so widespread. What explains this terminal decline of India’s grand old party? Veteran congress leader Ghulam Nabi Azad makes us believe that the party suffers from a leadership crisis and a lack of inner party democracy.

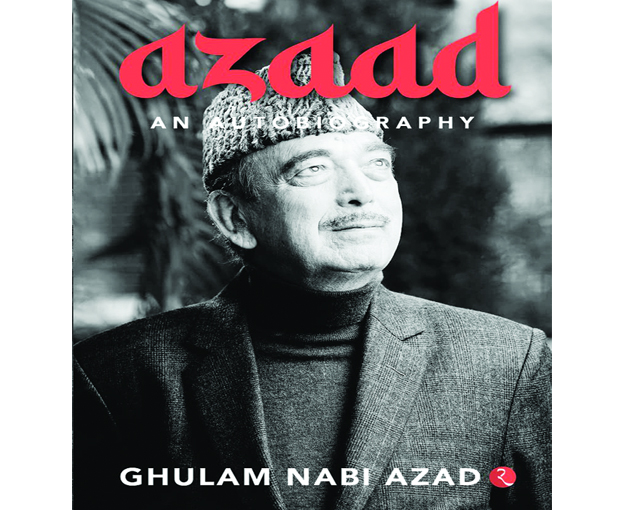

In his recently released autobiography titled ‘AZAAD’- he writes that the Congress’s biggest handicap is its oversize dependence on the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty which is past its sell-by-date. He describes the behavior of his former party as ‘bloopers and bombast’. However, he doesn’t adequately illuminate how Congress ought to process the ascendancy of Hindu nationalism.

Azad talks about the letter that G 23 leaders wrote to Sonia in August 2020 seeking changes in the way the party was being run. Unfortunately, instead of taking the letter in the right spirit, both Rahul and Sonia took offence and viewed it as a challenge to their authority. ‘We were dubbed as pro and BJP.’

In his book, Azad showcases the grand arc of the great India story through the most dramatic political events since he joined the Indian Youth Congress in the 1970s when Sanjay Gandhi was at the helm of affairs.

A Union Minister at the age of 33, a former Chief Minister, seven-term Member of Parliament, a former Leader of the Opposition and a member of the Congress Working Committee – Azad’s career has been distinctly eventful. The book refers to his close interactions with different political figures across party lines, particularly with the Gandhi Parivar-Indira, Rajiv, Sanjay, Maneka, Sonia and her children, Rahul and Priyanka.

He is unabashed in his admiration for Sanjay. He writes that it was he who proposed to Indira Gandhi that the Congress celebrate Sanjay birth anniversary to keep his legacy alive. Accordingly, a huge rally was held where Rajiv Gandhi was introduced to the workers. One wonders what legacy Sanjay left.

He provides a ringside view of various strategic moves initiated by him: devising strategies in consultation with Indira to persuade Rajiv to join politics and convincing Sonia to become the party chief. Giving example of Himanta Biswa Sarma, he hints at the emasculation of regional leaders so that the dynasty remains the party’s biggest draw. But can one deny that the high command culture owes its birth to the Indira era.

He does not hesitate to offer unbiased opinions on Congressmen- describing former Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao as ‘crafty’, refers to political tricks played by N.D. Tiwari and Mufti Sayeed. However, it is his relationship with both Sonia and Rahul (describing him as ‘meddling’) that is not only insightful and intimate, but utterly entertaining.

He laments the unfortunate 1990 exodus and admits the use of loudspeakers by the militants to frighten the Pandits to leave the valley. “The militants used loudspeakers to spread the message, asking Kashmiri Pandits to leave Kashmir. Contrary to general belief, not all the clerics in charge of the mosques were supportive of the militants; in fact, most of them actually supported Pandits. Some of them made those announcements out of fear of the militants rather than out of sympathy for them. However, the fact remains that the Pandits were harassed and many lost their lives at the hands of militants. Fearful of their lives, the Pandits began leaving Kashmir, ultimately abandoning their homes and hearths.”

He is at pains to describe the migration a blot on the people of Kashmir in general and the Janata Dal government in particular, whose representative, Governor Jagmohan, was heading the government of J&K at that time. However, he does make a somewhat controversial remark when he states that the state facilitated their migration.

One may pose a counter argument: how come a large number of Pandits- particularly in rural areas- who braved the turmoil and fear of 1990 and opted to stay put in the valley were made to flee much long after Jagmohan had ceased to be the Governor. What about the Wandhama and Nandimarg massacres of 1998 and 2003 respectively? And how does one explain the recent killing of Pandit employees posted in the valley.

Incidentally, Azad family too was targeted by the terrorists with one of his close relative Mohammed Amin fired at while coming out of office.

Azad refers to the meeting he has had with Sonia when congress was voted back to power in 1991. After ruling out Arjun Singh and a few more senior congressmen, he proposed the name of Narasimha Rao to Sonia who said that ‘he is a fine man and a good choice.’

However, this is not the whole truth. According to a more credible account provided by Natwar Singh who then was a close aide of Sonia- the name of Narashimha Rao was proposed by the late P.N.Haksar whom Sonia had consulted after the 1991 verdict.

The greatest anguish the author expresses relates to the aftermath of 2002 elections to J&K state assembly. The National Conference, which won 28 seats to emerge as the single largest party, declined to form the government. The Congress, with Azad as its leader, won 20 seats and the PDP of Mufti Sayeed managed 16 seats.

According to Azad he managed to secure the support of 42 MLAs- with several independents and smaller parties extending their support, but he was keen that Mufti joins the government- with CM’s position offered on a rotational basis.

Mufti proved smarter and instead formed the government with the support of the Congress party. Apparently, Sonia played a key role in passing the State baton to Mufti much to the disappointment and perhaps shock of Azad. The author fails to illuminate as to what influenced Sonia to tilt towards Mufti at the cost of her own party.

However, Azad’s account has been disputed by PDP veterans Naeem Akhtar who dubs these claims as “blatant lies” and a “cock and bull story”. “It was Ms. (Sonia) Gandhi who sent Dr.Manmohan Singh in 2002 to Kashmir to negotiate the alliance’s agenda. It took two months to finalize the document,”Akhtar adds.

Perhaps, the truth lies somewhere in-between: while Azad was busy staking a claim to form the government he was unaware of the discussions that Sonia and Mufti were simultaneously having about the cabinet formation.

There are few places when the author prefers not to elaborate. He admits meeting astute political observer having strong affiliation with the Congress party, Ashok Bhan, senior advocate of the Supreme Court over coffee at Broadway Hotel, Srinagar at a time when state politics was in a flux. He tells Bhan that he should ask Mufti to join the government but does not divulge further details of what else was discussed.

Azad doesn’t hesitate to describe two important state congress leaders – Ghulam Rasool Kar and Mangat Ram Sharma- ‘thick as thieves’.

The author takes pains to explain the various development initiatives undertaken by him when working as a Minister at the centre and as Chief Minister. In particular, he highlights the augmentation of health infrastructure in the state, and does not forget to mention his dream project – the Tulip Garden in Srinagar and Golf Course in Jammu. He blames the PDP for objecting to his proposal to creating a huge lake at the base of Bahu Fort up to Sidhra bridge on the river Tawi.

There are a few errors like mentioning M.S.Gill as secretary of I&B Ministry, whereas it was S.S.Gill.

Azad fondly remembers the village Soti in Bhaderwah Tehsil where he was born. After attending the school in Kilhotran, he joins Gandhi Memorial Science College, Jammu and S.P.College and Kashmir University, Srinagar, securing MSc in Zoology.

Active in politics since his student days, Azad campaigned for Dr Karan Singh when the latter contested the 1977 Lok Sabha elections from Udhampur constituency.

Married to singer Padma Shri Shameem Devi, Azad informs us of her singing talent – lending voice to some of the popular TV serials including The Sword of Tipu Sultan, The Great Maratha and Jai Hanuman, apart from performing on Akashvani and Doordarshan.

The question that remains unanswered is whether the ills afflicting the party are solely about leadership or also lie in its failure to foster a new outlook and devise a new language that reflects the aspirations of 21st century young India?

Also, is it not true that most Congressmen including those who have recently left the party, fail to acknowledge that today, Hindutava in 2023 has ceased to be just a word. For a significant majority community, it represents a movement towards self renewal with energies directed towards reclaiming the civilization ethos and richness of Bharat.

One was hoping Azad would also examine some of these challenges facing the party considering his long stint at the centre of power.

Meanwhile, Azad has formed a new political party ‘Democratic Progressive Azad Party’- identifying abrogation of Article 370 and 35A as the main challenge before it.

The book has many visually arresting photographs, augmenting the story of Azad’s political and personal voyage. The publication is recommended to anyone who is interested in India’s contemporary politics and the developments in J&K. The flow of the narration keeps the reader glued to each sentence written. It exudes both nostalgia and anguish.

Azad talks of his personal equation with Prime Minister Narendra Modi whom he describes as a ‘great listener.’ I have never spared him on the floor of the House. Yet he was generous in praising my performance as Leader of Opposition.

If we agree that in the times we live in ideology has come to constitute an ‘imaginary relationship’, then one shouldn’t be surprised if Azad warms up to BJP. However, only time will tell whether that will make AZAD truly ‘AZAAD’.

(The author works for reputed Apeejay Education, Delhi)

Trending Now

E-Paper