Ashok Ogra

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the Constituent Assembly of independent India was heavily loaded in favour of upper castes. But for the relentless efforts of Ambedkar (who was also the Chairman of the drafting committee) and few more members, the genuine concerns of the millions of disadvantaged and marginalized sections of our society would have received cursory mention. One such member who argued forcibly in the constituent assembly for protecting the interests of the Adivasi (Adibasi in local parlance) was Jaipal Singh Munda – himself a tribal.

Speaking for the first time as a member of the Constituent Assembly, Jaipal Singh Munda owned up his tribal heritage and spoke about casteism and patriarchy in mainstream Indian society. ‘As a jungli, as an Adibasi, I am not expected to understand the legal intricacies but my common sense tells me that every one of us should march in that road to freedom and fight together. Sir, if there is any group of Indian people that has been shabbily treated it is my people. They have been disgracefully treated, neglected for the last 6,000 years. The history of the Indus Valley civilization, a child of which I am, shows quite clearly that it is the newcomers – most of you here are intruders as far as I am concerned – who have driven away my people from the Indus Valley to the jungle fastness. The whole history of my people is one of continuous exploitation and dispossession by the non-aboriginals of India punctuated by rebellions and disorder, and yet I take Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru at his word. I take you all at your word that now we are going to start a new chapter, a new chapter of independent India where there is equality of opportunity, where no one would be neglected,’ he said.

Both in the constituent assembly and later when elected to Lok Sabha from Ranchi, Jaipal Singh came to represent tribals not just of his native plateau, but also of all of India. He was a gifted speaker; whose interventions as an MP enlivened and entertained the debates.

Sadly, Jaipal’s contribution to the welfare of tribals is not known to the majority of Indians.

How many Indians know that Jaipal Singh Munda was captain of the hockey team that won gold at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics?

How many Indians know that the brain behind the 5th and 6th schedule of the constitution when adopted on 26 November 1949, was Jaipal Singh Munda?

How many Indians know Jaipal Singh Munda, an Adivasi, became the president of the Oxford Indian debating Society in the 1920s?

How many Indians know that Jaipal Singh Munda resigned from ICS in 1928 to serve the cause of Indian sports?

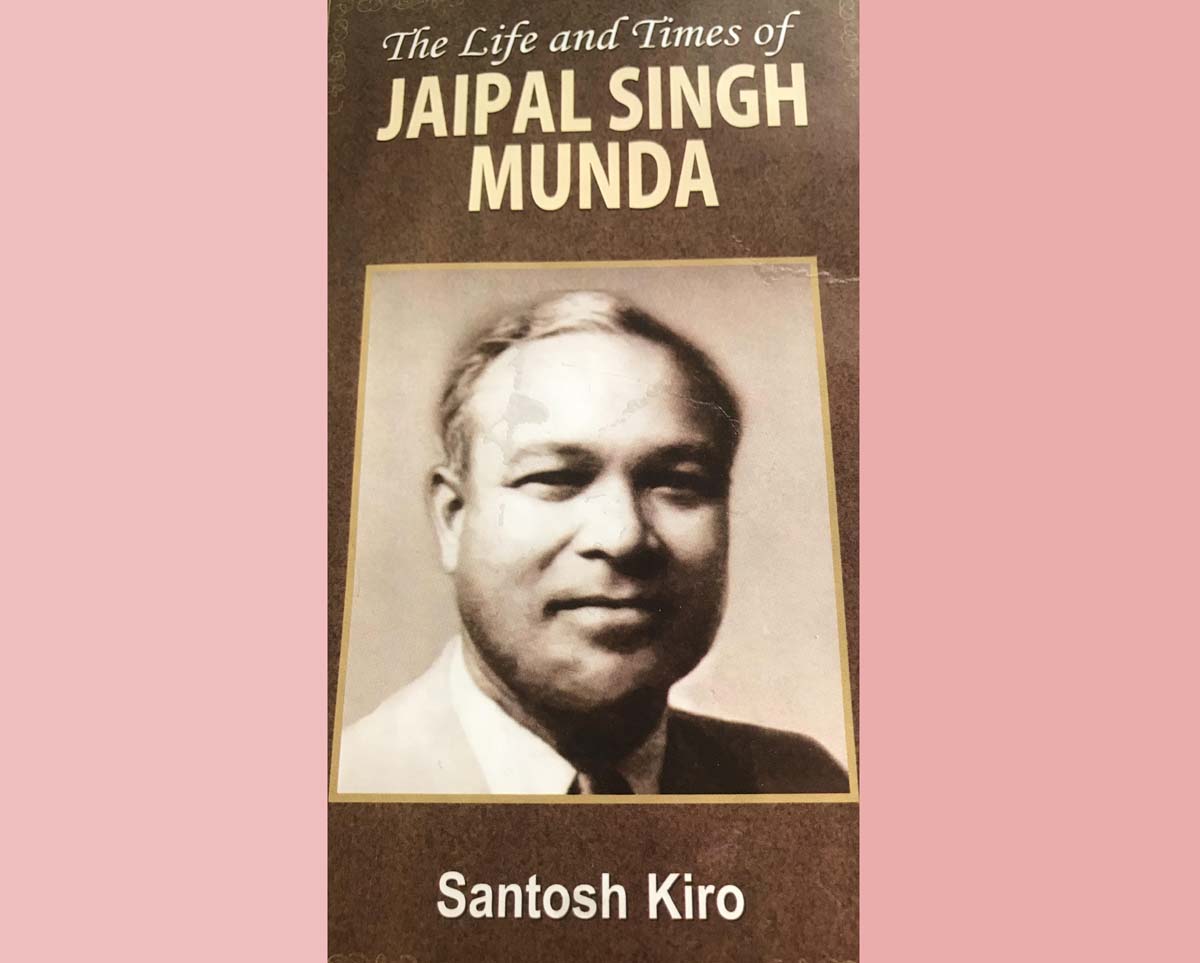

In this regard, the biography titled ‘The Life & Times of Jaipal Singh Munda’ written by my friend Prof. Santosh Kiro-fills the gap and delivers a detailed close up of this great son of India.

Born to Amru Pahan and Radhamuni on January 3, 1903 in Takra Pahantoli village, near Ranchi, the family belonged to Pahan tribe who were the priestly class in Munda families. They named their second child Pramod Pahan.

Initially, he went to a village school where he learned basics. No fee was required to be paid except that ‘at the end of the harvest every household gave one mound of paddy.’ Going by the overall conditions of Adivasis that time, the Pahan family were rich and owned two horses.

The author provides a rich account of Adivasi lifestyle: ‘for the Mundas, hunting wild animals had been a sport that no elderly young men or the male children wanted to miss, unless unwell or physically crippled. … It was one occasion when youngsters would call names to the elders, without any danger, with impunity.’

Santosh continues that at the end of the hunt, the elders however assumed their superior social position and met in a council to judge outstanding village disputes.

After initial schooling in the village, he was admitted to St Paul’s School, Ranchi- run by the Christian Missionaries of SPG Mission of the Church of England. It was when admitting his son at this school that the father gave him the name Jaipal Singh Munda. He showed his extraordinary talent in sports -particularly hockey- and excelled in academics. The Principal of the school Canon Cosgrave who was a wealthy priest from England and had donated his entire wealth to the college took a special liking for young Jaipal. As the luck would have it, after a few years Canon was transferred back to England. While leaving, he announced that he was going to support Jaipal’s higher studies at Oxford University in England.

Jaipal did not take much time to demonstrate his brilliance in academics and mettle as a hockey player. He went on to represent Oxford University where he was conferred Oxford Blue.

Santosh narrates an interesting fact that will certainly surprise many of us. India decided to send a hockey team to the Amsterdam Olympiad in 1928. At that time Jaipal was undergoing training as an ICS probationer. The hockey federation offered Jaipal to be the captain of the Indian hockey team – an offer Jaipal couldn’t resist. His request to the British authorities for leave from training was refused. He was in a dilemma – whether to play for the country or forego a career in ICS which held in store great opportunities, social recognition, unprecedented dignity, secure life and unquestioned authority with the British at the helm of power.

However, Jaipal’s love for his motherland and hockey forced him to defy the rules and resign from ICS. This was a rare case of true patriotism before personal interest. The Indian hockey team bagged the gold. Both legendary Dhyan Chand and Shaukat Ali were part of the squad. Sadly, Jaipal could not play in the finals because of differences with the English coach.

Actor Akshay Kumar’s movie Gold, inspired by Indian hockey’s 1948 Olympic gold win, celebrates the legacy of Kishen Lal who captained the Indian team to win their first gold as an independent nation. But it is forgotten that this victory came on the back of three consecutive gold medal wins for the country while still a British colony. The first one of those victories, in 1928, started the fable of Indian hockey.

As president of the Indian Oxford Majlis, Jaipal interacted with personalities like C. F. Andrews, Annie Besant, and Lala Lajpat Rai. His contemporary N. G. Ranga of Swatantra Party recalled, “Even in those days Jaipal would never tolerate denigration of Indians by the British, he was unique in many ways.”

Soon after resigning from ICS, Jaipal worked for Burma- Shell in Calcutta. It was during this time that he met Tara Mazumdar- the granddaughter of the first President of the Indian National Congress, W.C. Bonnerjee. They took a liking for each other and got married in St. Paul’s church in Darjeeling.

Jaipal also served as Principal of Rajkumar College Raipur, and Foreign Secretary in the durbar of Maharaja of Bikaner.

But his heart was aching to serve his people. He returned to his home city Ranchi in 1938 and a year later was elected President of the Adibasi Mahasabha thus heralding a new chapter in his long and illustrious life.

Santosh Kiro has done incredible research in documenting the struggle by Adivasis demanding their genuine rights- beginning with the Birsa Munda-led rebellion ‘Ulgulan,’ meaning ‘Great Tumult’ (1899-1900), which took place in the south of Ranchi. It is seen as a landmark incident in the agrarian history of tribal India. It was against encroachment and dispossession of tribal land. As a result of his efforts along with others, that the Constitution included multiple safeguards for tribals and provided them reservations among other things.

His dream of a separate state for the tribals was realized on 15 November 2000, when Jharkhand was created, but he wasn’t alive to cherish it. Jaipal died on March 21, 1970.

Prof. Santosh Kiro deserves praise for documenting the life of this great social reformer cum architect, parliamentarian, excellent sportsman, sports journalist and an administrator, and for the tribals of Chotanagpur, ‘Marang Gomke’ or Great Leader. The book is published by Prabhat Prakashan, New Delhi. One wishes the author had also included photographs – particularly of the 1928 Olympics, and also provided an index.

However, Munda will always be known as the man who brought the story of the tribals to the centre stage of Indian politics. But unlike Ambedkar who now justifiably enjoys a god-like standing among average Indians across castes, Jaipal Singh Munda continues to be viewed only as a tribal statesman and remains ‘unsung’ and ‘uncelebrated’ in the rest of India.

(The author works for reputed Apeejay Education Society, New Delhi)