Lalit Gupta

Modern studies have revealed that writing system is not a marker of civilization but at the same time it certainly signifies an important development in the intellectual progress of a culture and concomitant changes in mental and social structures incident to the use of writing.

In the above context, introduction of literate culture in Jammu region-which boasts of great scoio-cultural continuum from Neolithic times along with wealth of oral literature-can be traced back to the 2500 BCE old Indus Valley Culture; the archaeological evidences of which were unearthed by Archaeological Survey of India at Manda, Akhnoor in 1960’s. Jammu being Indus Valley culture’s northern most outpost must have had exposure to the earliest system of writing in the sub-continent.

After decline of Bronze Age culture of Indus Valley by end of second millennium BCE, the later day culture associated with use of painted grey ware (PGW), was considered as the threshold of second urbanization in India roughly between 1200 BCE to 600 BCE. It was followed by the culture of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBWP) people who in turn laid the foundation of super structure that around 6th century marked the establishment of legendary republics; the 16 Maha-janapadas (including Madra janapada–with Sialkot as capital) ruled by kings like Udayana, Prasenjit and Bimbisara, and marked with the great religious teachers, Mahavira and Buddha.

It is during the time of second urbanization that Jammu region, under the sovereignty of Gandhara and Madra Desh, due to its unique geographical position not only emerged as an important mountainous tract and a safe haven for the commercial traffic emanating from Indian mainland to Central Asia via Gandhara but was also exposed to contemporary urban culture and practices.

Another landmark development that left an indelible imprint on the socio-religious life of Jammu region was advent of Buddhism in the region from circa 5th -4th century BCE onwards. This also led to a process of acculturation that entailed series of changes in the socio-cultural life of the indigenous communities. The material evidences of such a social-cultural transformations in target communities was directly related to factors like, the patronage of Buddhism by local ruling class, social elite and traders caravans passing through this particular area. Such evidences have come in terms of growth of monastic complexes in and near cities, growth of literacy.

Buddhist monastic complex at Ambaran, near Akhnnor, which flourished between circa 1st century BCE to 6th-7th-century CE, along with many such unexcavated monasteries in the region, played pivotal role in exposing the local hill and highland communities of Jammu to Buddhism and the aura of power associated with it; partly because this religion had the support of powerful regional political forces, and partly because Buddhist monks were recognized for their scholarship. Since each region to which Buddhism traveled developed its own monasteries, universities, temples, and dedicated lay followers, the region of Jammu was no exception.

With reference to development of scripts and literacy after Indus valley, the earliest recorded scripts of India are Brahmi and Kharoshti. It is not definitely known when these scripts came in use, but by time of king Ashoka they had established themselves as widely used scripts.

Kharoshti script enjoyed popularity in ancient Gandhara Culture to write the Gandhari and Sanskrit language remained in active use from the middle of 3rd century BCE until it died out in its homeland around 3rd century CE.

According to scholars, Brahmi, the mother of most Indian and South-East Asian scripts which evolved during and after the Mauryan era widened its reach through traders travelling to these regions. Earliest examples of Brahmi script, in form of Ashokan Edicts, stand etched on pillars and rocks spread through the length and breadth of Indian sub-continent. In the north-west of India, Ashokan rock edicts have been discovered at Kandhaar in south Afghanistan and Shahbazgarhi in NWFP, Pakistan.

Though no Ashokan rock edicts has been discovered in Jammu and Kashmir, the earliest available Brahmi inscription in Jammu region that links the development of literate culture in Jammu with pan-Indian cultural achievements, has been discovered from Bathastal (Balastal) Cave in Dachhan, Kishtwar. This post-Mauryan Brahmi inscription was first noticed in 1921 by R.C.Kak, the prime minister of princely state of Jammu and Kashmir and an archaeologist of repute. Dated between 3rd to 5th centuries CE by R.C. Kak, the Bathastal inscription is one of the oldest Brahami inscriptions in Jammu region. Epigraphist like B.K.Kaul Dembi have placed and compared Bathastal cave inscription with coins of Indo-Bactrian kings Agathocles and Pantaleon, Rock inscription of Khanihara, near Dharamshala in Himachal Pradesh and Inscription of Kshatrapa King Sodasa, all belonging to Post-Mauryan Group of 184 BCE to the beginning of Christian era.

Second important inscription in Jammu region is the Bhadarwah Cave Inscription which is inscribed inside a cave shrine (called as Gupt Ganga) on the bank of river Neru near Bhadarwah town. According to B K Kaul Dembi, it is perhaps the longest Brahmi inscription in the region and also the second oldest Brahmi inscription from the Himalayan Valleys of Chenab region. Thirdly, its paleographic studies indicate the Kushana influence in the Valley of Bhadarwah.

The third important Brahmi inscription has been found inscribed on an iron trident, that broken in two pieces, stands embedded in the courtyard of Sudhamahadev Shiva temple. On the basis of paleographic evaluation by J.N. Agarwal, this inscription which mentions one king Ganpati Naga son of Vibhu Naga, has been dated to 3rd-4th century CE.

The Ganpati Naga, who also finds mention in the famous Allahabad Pillar Inscription, was one of the nine Naga rulers conquered by the great warrior king Gupta emperor Samudragupta. During 3rd and 4th century CE, two Naga families ruled, one belonging to Mathura and the other to Padmavati (modern Gwalior). Many coins of that period disclose names of ten Naga rulers, including Vibhu Naga and Ganapti Naga.

Sudhamahadev temple inscription throws important light on political history of Jammu and establishes the fact that Sudhamahadev was an important pilgrimage centre in 3rd-4th CE which attracted visits from kings, especially those who also had influence in this area.

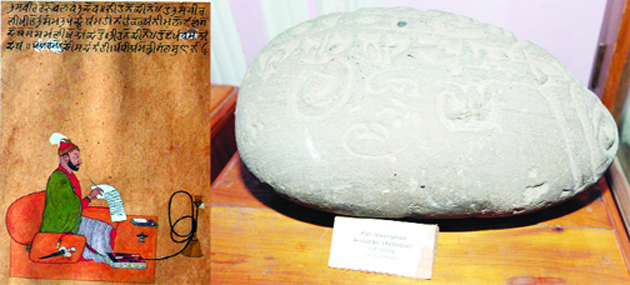

In the background of already existing practice of writing inscriptions in Brahmi, the other evidence reflecting upon the use of another special variety of script in Jammu is linked to the discovery of so-called Shankha Lipi inscriptions found on small round stones at Akhnoor (now lying in the collection of Dogra Art Museum, Jammu) and also on stone boulders near Bhadarwah.

Interestingly, these un-deciphered short inscriptions-in a script called as ‘Shell characters’ or ‘Shankhalipi’ for their peculiar and highly ornate character-are also found at a wide range of archaeological sites in and around India from Akhnoor (Jammu) in the north to Sandur (Bellary District, Karnataka) in southern India as well as from four sites in Indonesia (Java and Borneo).

Since Sankha Lipi, has been used for names and signatures by the pilgrims as record of their visits to famous pilgrimage centers. The finds of such inscriptions in Akhnoor and Bhadarwah, clearly establishes that their find spots (such as the monastic complexes Ambaran (Akhnoor) and Bhadarwah) were active centers of pilgrimage in Jammu between 4th to 7th century CE.

Next stage of literacy/writing in Jammu and contiguous regions of Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir is linked to a western variant of Gupta Brahmi script which developed between the 8th-10th century CE and evolved into ‘Sharda’ script which was used mainly in Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu, from 8th century CE onwards,

‘Sharda’, in turn grew into several variants in a few centuries. By 10th century, the first variant, the ‘Landa’ script, had appeared in Punjab, and would eventually transform into the Gurmukhi script. By 14th century other variants such as ‘Takri’ and Kashmiri also appeared in Jammu and Kashmir regions respectively.

Infact ‘Takri’ descended from ‘Sharda’ through an intermediate form known as ‘Devashesha’, which emerged in 14th century. ‘Devshesha’ was a script used for religious and official purposes, while its popular form ‘Takri’ was used for commercial and informal purposes. ‘Takri’ became differentiated from ‘Devshesha’ in 16th century and served as the official script of several princely states of northern and north-western India, from 17th century until the middle of 20th century.

The Dogri form of ‘Takri’ was adopted as the official script of Jammu and Kashmir and a standardized form of the script, known as ‘Dogre Akkhar’, was propagated by official decree by Maharaja Ranbir Singh of Jammu in 1860s. Ranbir Singh also established the Vidya Vilas Press in Jammu in order to print scholarly books and official publications including revenue rules and measurements etc, in the new Dogri script.

‘Takri’ appears in numerous records, from manuscripts to inscriptions on stone slabs, metal sheets, memorial stones, baolis, buildings, wells etc. It was used for writing administrative documents, such as letters, land grants, and official decrees. It appeared on postage stamps and postmarks from Jammu and Kashmir from 19th century.

Translations of Sanskrit texts into Dogri language printed in Dogri ‘Takri’ were commissioned by Maharaja Ranbir Singh. The most well-known of these is the mathematical treatise Lilavati by Bhaskaracarya. The British and Foreign Bible Society printed translations of Christian religious texts in Takri. The most well-known of ‘Takri’ records are inscriptions on Pahari paintings, which as a distinct style of miniature painting developed in former princely states such as Basohli, Mankot (Ramkot), Chamba and Kangra. Pahari miniatures often contain captions that indicated subject of a portrait or a description of a scene written in the local language using Takri, or excerpts from a literary text

Until late 19th century, ‘Takri’ was used concurrently with ‘Devanagari’, but it was gradually replaced by Urdu. The Dogri ‘Takri’ finally lost its socio-cultural status on a decision in 1944 by the Dogri Sanstha to use Devanagari as the official script for the Dogri language.

Trending Now

E-Paper