Ashok Ogra

Living a migrant life involves settling and unsettling experiences. The loss of an abode can lead to a longing that goes from minor to traumatic. For Kashmiri Pandits (KPs), forced to migrate en-mass in 1990, the pain of ‘missing’ comes out too strongly.

Migration invariably involves three stages: Suffering, Struggle and Stability. For most of the KPs, the first ten years from 1990 were spent in complete suffering and hopelessness. The pain of missing was too much, and they would often wonder why they were made the target by the terrorists -both home grown and Pakistani Jihadis. Sometimes, the guilt of why they left the place would seize them.

During the next decade (2000-2010), the hope they would be able to return started fading. Thus, the community focused on rehabilitation and resettling their lives including ensuring education for their children and most constructing houses in Jammu and elsewhere to escape the conditions of living in the ‘migrant camps’.

It was in the third decade of 2010 onwards that most KPs seemed settled to a new life with children having secured decent jobs – both in India and abroad.

However, moving to distant places – both in India and abroad- as much it brings possibilities and opportunities, it also inexorably entails many losses that are hardly ever acknowledged.

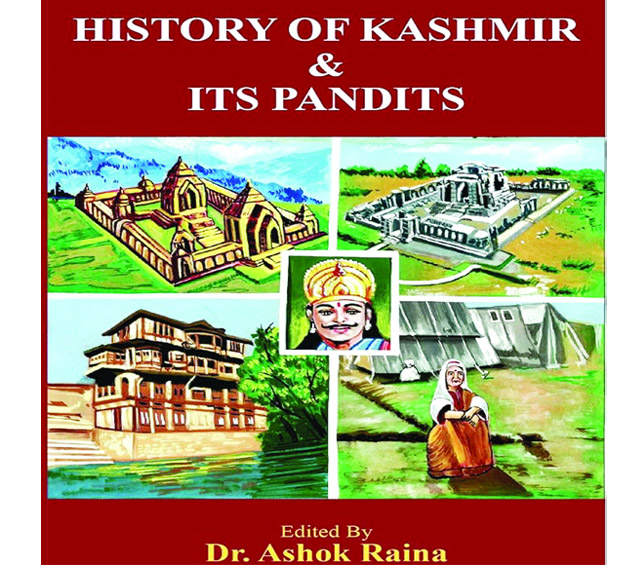

US based scientist turned author Dr. Ashok Raina effectively captures the present dilemma facing the community in the book History of Kashmiri & Its Pandits that he has edited: “Throughout the past nearly six centuries, Pandits have mastered the art of self-preservation. They have survived as individuals through the most adverse conditions. They found their strength in learning through education, hard work, and inner drive for success in whatever field of employment they chose. However, will Pandits ever be able to return to their homeland? Unless the majority community accepts the Pandits as equal shareholders of Kashmir and the two communities learn to live together in peace, the Valley is going to be in perpetual turmoil, and the Pandits will continue to remain homeless.”

As a unique selling point, Dr. Ashok Raina brings together a diverse range of distinguished Pandit voices from across the world. In his foreword, Padmashri Dr. Subash Kak hopes that the political situation in the Valley will improve and some of the displaced Pandits will be able to return.

One is tempted to ask both the distinguished contributors whether peace in the valley is only dependant on the wishes of the two communities – namely Muslims and Pandits. What about the role of Pakistan that thwarts any attempt aimed at bridging the gulf between the two communities?

Noted community activist, Dr. (retd. Col) Tej Tikoo, questions the versions of some of the historians who have cast Dogra Raj (1846-1947) as inimical to the majority community. With facts, he demonstrates their useful contribution in uplifting the state subjects from poverty and backwardness. From introducing land reforms to setting up educational institutions, from strengthening irrigation systems to establishing hospitals, the Dogra rulers were the pioneers when compared with other princely states. The author dwells at length on the political developments of the 1930s that shaped the future course of Kashmir history till 1947.

Noted author, Prof. Tej. N. Dhar provides an absorbing account of the supremacy of the Shaivite philosophers and their debate with the Buddhists. “Khemraja, the disciple of Abhinavgupta, is believed to have said that when Vasugupta invoked the help of Shiva for taking part in a debate with the Budhhists, Shiva visited him in his dream, told him to go to the foot of the Mahadeva Mountain and read Siva-Sutras engraved in a rock. He promptly followed the advice and defeated the Buddhists.”

In another article titled ‘The Hindu Rulers’, Prof Dhar, with great clarity, elaborates on the prominent king of Kashmir, Lalitaditya Muktapida

) whose rule he describes as the golden age in Kashmir. “Lalitaditya was not only a great warrior but also a benevolent ruler and a great patron of science, arts and architecture.… he built temples for Buddha as well as for gods like Shiva and Vishnu and Viharas, where scholars from both religions enjoyed royal patronage and made additions to scholarly knowledge,” he further adds.

The arrival of Islam in landlocked Kashmir is the focus of Padmashri

Dr. Kashi Nath Pandit’s article ‘The Muslim Rule’. He notes that the task of carrying an Islamic banner to Kashmir fell not to the warriors but to the proselytized Iranian and Turanian (Turkistani) missionaries in the second half of the 14th century. He sheds further light: “Islam was brought to Kashmir by the descendants of the proselytized Zoroastrians, not the indigenous Arabs.”

One of the major beneficiaries of the 1990 migration has been a renewed interest among the Pandits in the ancient history of Kashmir. In their essay ‘Kashmir Valley: Evolution and Pre-history’, both Dr. Sundeep Pandita and Dr. Ashok Raina traces our roots with the skill of an archaeologist : “The trial excavations by Dr. Terra and Paterson have shown that two cultural layers existed in the area. The uppermost layer with potsherds belonged to the Buddhist period, which represents the fourth century AS. The second layer below, with highly polished black ware and potsherds with incised geometric designs, belonged to the late or early phase of the Indus Valley cultures, ranging from 3000 to 1800BC.”

Both the authors succeed in inciting new thoughts and inspiring readers to continue exploring the past to gain better understanding.

In ‘Post-Independent Kashmir’ Dr. Bansi Lal Kaul briefly touches upon the important events of the state since 1947. He faults the then leadership in the manner the Shimla agreement was concluded: “having secured the release of the Pakistani prisoners of war from India, Bhutto started talking of a thousand year war with India to avenge the humiliating defeat of his country and the loss of East Pakistan.”

Dr. Pandit’s article on the Tribal raid of 1947 provides graphic details of the savagery let loose by the Pakistani raiders on the Hindus and Sikh population.He reveals that well known Pakistani personalities, including the Faquir of Manki Sharif and the Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, visited Baramulla to boost the morale of the Tribal Lashkars.

With an interdisciplinary flavour, the book draws from cultural history and political science to shed light on the survival instinct of the KPs. That is what Bansi Lal Pandit brilliantly brings out in ‘Pandits and their Unique Culture’. He claims that there is no historical data to show when Saraswat Brahmins became Bhattas. “The word Bhatta is derived from the Sanskrit term Bhartri, which means ‘doctor’ or ‘intellectual’. Exactly how and when the term Bhattas eventually came to be known as present day Kashmiri Pandit is not known.”

The authors have succeeded in providing sketch of the history of Kashmir and its Pandits. The book makes for easy reading and has useful references at the end of each chapter.

In the chapter ‘The Genocide of Hindus of Kashmir’, the authors :

Dr. Satish Ganjoo, Ashwani Chungroo and Dr. Ashok Raina- recount the contempt and discrimination and killings of the Pandit community starting with Sultan Sikandar – the Butshikan or idol breaker (AD 1389-1413), and gaining traction with subsequent Muslim rulers . They provide a haunting portrayal when describing the onset of terrorism in Kashmir in 1990.

The authors raise a valid question: “Some Pandits took the abrogation of Article 370 and 35A as a positive sign and started going back to the valley. Others were motivated by the offer of government jobs. For the Jehadis, this would mean a failure of their plan of total Islamization. Consequently, they returned to their old tactics of killing one and, this time, scaring a dozen because there were no thousands left to be scared. Under these circumstances, will it ever be possible for the Kashmiri Pandits to go back to Kashmir?”

What emerges from reading this account is that the more Pandits long for home, the father away it appears. That explains why most migrants continue holding on to the pieces of the past while waiting for the future.

This is the thrust of Dr. Vijay Sazawal’s article ‘Will Pandits Survive without Their Kashmir’. Being one of the leading lights of the community,

Dr. Sazawal is best qualified to examine this question from a wider canvas. He is kind enough to provide his own conclusions: “The worst is probably over for the Shaivite Hindus living in the valley. Their primary challenge is to survive economically, and the past three decades have shown that Valley Pandits have discovered ingenious ways to acquire new skills to succeed in hostile environments. He goes on to paint a somewhat rosy picture: As militancy dies in Kashmir and the promised prosperity returns, Valley Pandits will grow in numbers from within. The prospect of peace will also likely help attract some displaced Pandits to return, especially those belonging originally to the rural areas of the valley. For those Kashmiri Pandits who live outside of the Valley, the bonds to their ancestral lands will never die.”

No one will argue with the optimism that Dr. Sazawal exudes. However, most Kashmiri Pandits face a dilemma. On one hand the hard fact that Pandits have built a life and left one behind. For them the valley that continues to witness targeted killing – is slowly becoming too invisible to follow back.

On the other hand is what Spanish psychiatrist Joseba Achotegui calls ‘migratory mourning’- emotions associated with the losses that are caused by migration? Isn’t ‘migration not only about leaving; it is also about returning?’

(The author works for the reputed Apeejay Education, New Delhi)

Trending Now

E-Paper