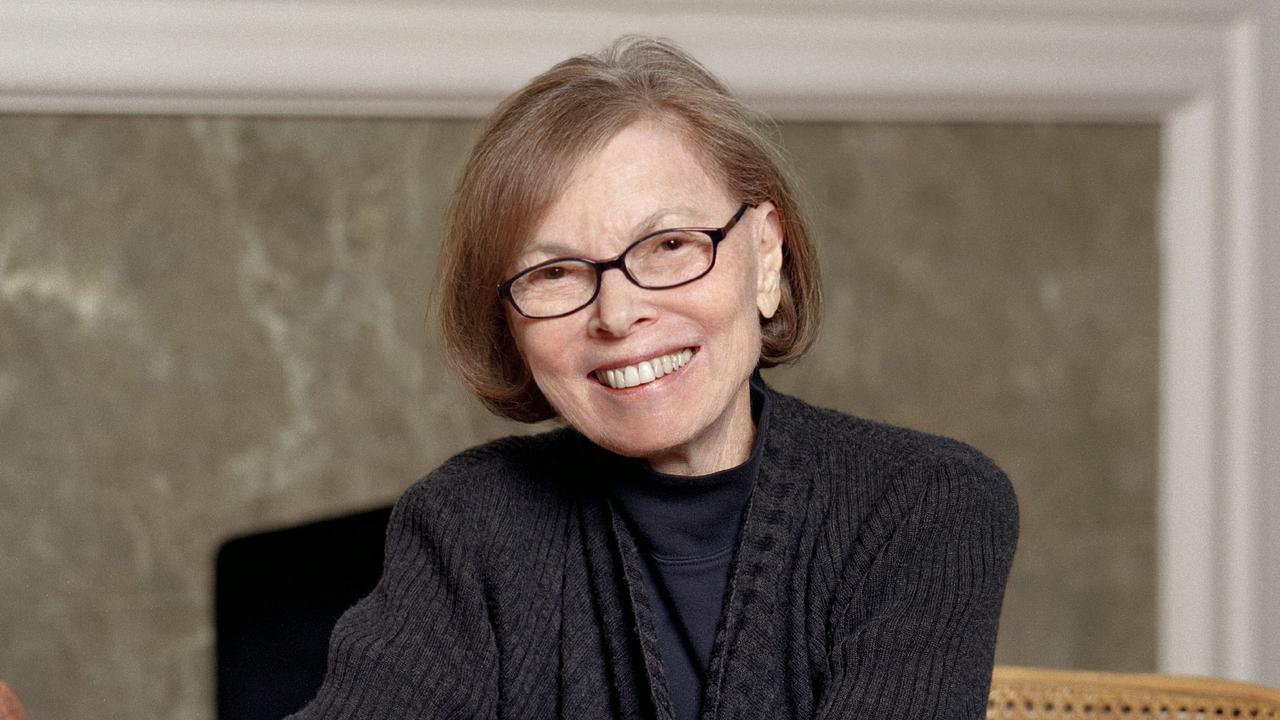

New York, June 18: Janet Malcolm, the inquisitive and boldly subjective author and reporter known for her challenging critiques of everything from murder cases and art to journalism itself, has died. She was 86.

Malcolm died Wednesday at New York Presbyterian Hospital, according to her daughter, Anne Malcolm. The cause was lung cancer.

A longtime New Yorker staff writer and the author of several books, the Prague native practiced a kind of post-modern style in which she often called attention to her own role in the narrative, questioning whether even the most conscientious observer could be trusted.

“Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible” was how she began “The Journalist and the Murderer.”

The 1990 book assailed Joe McGinniss’ true crime classic “Fatal Vision” as a prime case of the author tricking his subject, convicted killer Jeffrey MacDonald, who had asked McGinniss to write a book about him only to have the author conclude he was a sociopath. It was one of many works by Malcolm that set off debates about her profession and compelled even those who disliked her to keep reading.

Reviewing a 2013 anthology of her work, “Forty-One False Starts,” for The New York Times, Adam Kirsch praised Malcolm for “a powerfully distinctive and very entertaining literary experience.”

“Most of the pieces in the book find Malcolm observing artists and writers either present (David Salle, Thomas Struth) or past (Julia Margaret Cameron, Edith Wharton),” Kirsch wrote. “But what the reader remembers is Janet Malcolm: her cool intelligence, her psychoanalytic knack for noticing and her talent for withdrawing in order to let her subjects hang themselves with their own words.”

On Thursday, New Yorker editor David Remnick praised Malcolm as a “master of nonfiction writing” and cited her willingness to take on her peers.

“Journalists can be among the most thin-skinned and self-satisfied of tribes, and Janet had the nerve to question what we do sometimes,” Remnick told The Associated Press.

Malcolm’s words — and those she attributed to others — brought her esteem, scorn and prolonged litigation.

In 1983, she reported on a former director of the London-based Sigmund Freud Archives, psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson.

She contended that Masson had called himself an “intellectual gigolo,” had vowed he would be known as “the greatest analyst who ever lived,” and that he would turn Freud’s old home into a “place of sex, women, fun.” Her reporting appeared in The New Yorker and was the basis for the 1984 book “In the Freud Archives.” (AGENCIES)

Trending Now

E-Paper