Ashok Ogra

Srinagar (in the 1870s):

A boy was born to a wealthy Dhar family of Safakadal, Srinagar and named Bal Bhadra (Ballu). The boy’s father Kashi Nath Dhar had done precious little with his life and was flirtatious by nature. Heemal, the mother of the boy, was daughter of an influential nobleman, Divan Nand Ram Tikku. The couple was blessed with three boys and a daughter.

Lucknow (Kashmiri mohalla):

It was a home to the well-known Kaul family: Mrs.Sumali Kaul and her barrister husband. They had no children and were keen to adopt a boy belonging to a decent Kashmiri Pandit (KP) family. They approached relatives and priests both in Kashmir and outside but to no vain.Meanwhile, Mr. Kaul’s health deteriorated and he passed away. This further strengthened the resolve of Mrs. Kaul to adopt a child.

One Day in the life of Ballu:

Kashi Nath decides to visit Kheer Bhawani along with Ballu. After Puja, he goes for a stroll – perhaps looking for vulnerable damsels – leaving his son in the custody of his servants. While playing a game of hide and seek the servants lose contact with Ballu. The news spreads like wild-fire in the valley all wondering what must have happened to the Dhar boy. Both the Dhar and the Tikoo families are devastated. Massive search operations yield no results.

Lucknow (How Ballu returns):

After several agonizing months, it was found that Mrs. Kaul had engineered the abduction, and Ballu was safe and happy living with her.

When Kashi Nath comes to know of it, he decides to relocate to Lucknow to be with his son. He stays at the residence of Mrs. Kaul. After sometime, Heemal also joins them; happy to see and be with Ballu if not necessarily with her amorous husband.

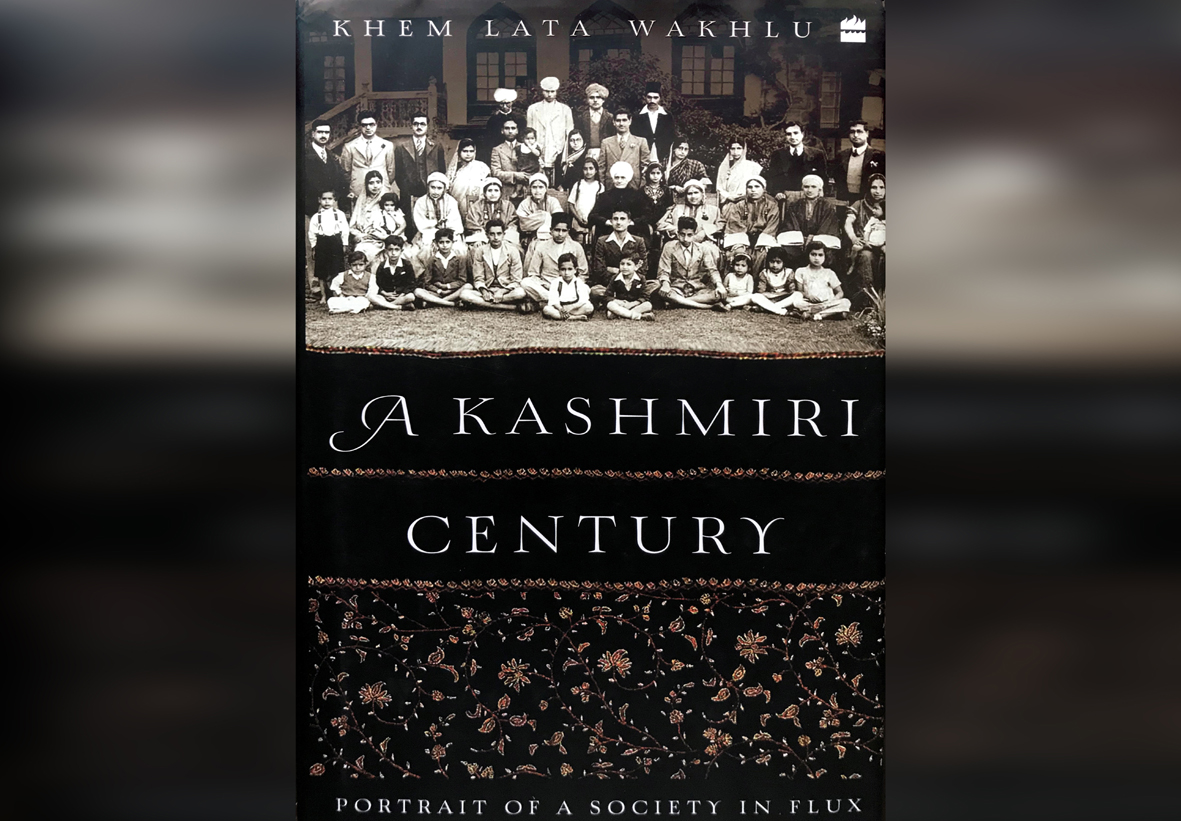

The above is a true incident recollected – candidly and honestly – by Khem Lata Wakhlu in her book ‘A Kashmiri Century: Portrait of a Society in Flux.’

As expected, the incident stunned the conservative Kashmiri society.

While the author may take comfort in nostalgia, the question arises:weren’t incidents of abductions rare in 19th century? If so, does it then truly reflect the portrait of our society that was fairly conservative during that period?The winds of change, if any, were slow in coming.

That aside, Khem Lata manages to bring to life the people and happenings thus presenting an honest and, at times, critical portrait of Kashmiri society in general and the Pandit community in particular – one where orthodoxies co-existed clumsily with the disruptions of modernity!

To her the book ‘delves into the human side of living in the Valley an aspect often missing in the cold political treatises on Kashmir. It offers a rare glimpse into lives of Kashmiris – Hindus and Muslims alike and how their pleasures’ existence revolved around the simple pleasures of life, even as they dealt with the many changes of the past hundred years.’

Khem Lata is the descendent of the Dhar family mentioned above; she became Wakhlu after marriage to late Prof. O.N.Wakhlu, Principal of REC (NIT), Srinagar. She is a well-known social worker, has been an MLA and Minister for Tourism during mid-1980s. Multilingual, she has to her credit many fiction and non-fiction books, and her play Kayama (Hindi) and Lale Sahib (Kashmiri) were adapted for television.

According to her the migration of the Pandits from the valley started from 12th century when they would visit Kasi, Ujjain, Leh, Puri and Lhasa, to provide guidance in writing books and for translating Sanskrit orSharda texts into the local language of the respective regions. However, during the tyrannical rule of some Muslim rulers who used sword to force conversions and persecute Pandits, the migration turned into a tide.

With regard to KPs managing the affairs of the Dogra kingdom, she informs that with the signing of the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846, the administration of far flung areas including Gilgit required educated and trustworthy officers. The Pandits were most suited because of their familiarization with Persian, Hindi, Urdu and Sanskrit. “These were not easy positions to be in since most in most cases the incumbent would be posted all alone,” she adds.

In the chapter ‘The Desire for Change,’ she acknowledges Kashyap Bandhu and Jai Lal Kilam who were endeavoring to make the KP community progressive in their outlook.”In fact, every Sunday, Kashyap Bandhu would organize a meeting of the community at the historic Sharika temple on the Hari Parbhat hill and share his ideas with the congregation. He was emphatic that modern KP women would have to switch over to wearing saris and blouses.’

Shiv Narain Fotedar too engaged himself in social service along with other notable social reformers of that time: Dr.S.N.Peshin, Justice J.N.Bhat,Shambu Nath Dhar, and Prem Nath Bazaz.

She makes an interesting observation about the old enmity between Abdullahs of National Conference and Mirwaiz Farooq: It was only in 1987 that the then Mirwaiz Maulvi Farooq joined hands with the old enemy, Farooq Abdullah. “That era of ‘Double-Farooq,’ as the unusual and unprecedented coalition of the Shers and Bakras was then known, resulted in a hardening of the Muslim identity in Kashmir.”

Barring such brief references, the author shies away from offering a grand narrative of political developments or an examination of the reasons that gave birth to militant insurgency.

I find her vivid description of celebrations surrounding festivals like Shivratri, Diwali, Dushera… both hilarious and brilliant as she weaves it into a family saga. “As the effigies were reduced to ashes, the other items of entertainment that had been planned for the evening commenced. The children, arranged in groups according to their ages, were brought in front of the spectators to do their little acts of singing, dancing, and making fun of the times through Ladishah style of poetry.”

There is nothing of significance that has escaped the author’s attention: she provides an entertaining anecdote concerning Nande Lal Bab who was an eccentric Kashmiri mystic. During early 1970s, word went round that that an educationist close to the Chief Minister would summarily replace the then Vice Chancellor of Kashmir University, Noor-ud-Din. Being a devotee of Bab, he immediately rushed to his ashram at Nunner village. On hearing his devotee’s story, the saint thundered: “I have given you this position! Nobody dare dislodge you!” Rest is history: Noor-ud-Din went on to complete his tenure.

The family of the author too paid a heavy price: first she and her husband were abducted, and later the militants kept Dr.Dhar in captivity.

It is a challenge to represent the voice of a community in one book but being an insider who has not only been a witness but a participant, Khem Lata has done an excellent job with finesse only a talented author like herself possibly could.

The book ends on a poignant note when Khem Lata recounts with great sensitivity the conversation that her brother Dr.Surender Dhar has had with his abductors: “Seeing him crying, one of the militants came forward and asked: ‘Why are you crying, doctor Sahib? Has anyone said something insulting to you?’ ‘No, no one has said anything to me, he replied. Then turning to the open window and looking out into the darkness, he added, ‘I am crying because our land has lost its soul!”

In that sense this book by Khem Lata Wakhlu will act as a reminder to our future generations – Once upon a time Kasmira was a sacred place that belonged to the pandits.

(The author is a management and media professional and currently works for reputed Apeejay Education Society.)