B L Razdan

Gyan, Karma, Raja and Bhakti were meditating deep inside a forest. Suddenly they were disturbed by a huge thunderstorm, which was accompanied by rain and hail. They rushed to the local temple, possibly the only building having a roof and held on to the Shivalinga there and lo, the Lord rose to bless all the four. It is only then that they realized that ploughing a lonely furrow in their respective line of Yoga had led them nowhere. Only when all the four paths combined did their efforts bear fruit.

By following one path to the total exclusion of other paths in the Yogic domain, it is difficult to realize God. There being a lot of common ground between various yogic paths, Gyan, Karma, Raja and Bhakti realized that regardless of the path each of them may have chosen, he or she should at least be conversant with the basics of the other three paths. Bhakti yoga is thus a common roadway usable by everyone who believes in loving God.

Bhakti means love and devotion to God – love and devotion to His Creation, with respect and care for all living beings and all of nature. Everybody can practice Bhakti Yoga, whether young, old, rich or poor, no matter to what nation or religion one may be belonging to. The path of Bhakti Yoga leads us safely and directly to the goal.

The concept of the so called Kashmiri Sufism is nothing but Bhakti Yoga where the practiotioners who would live a God-centred life and not a world-centred life, transcending all duality and being steadfast in their love for God.

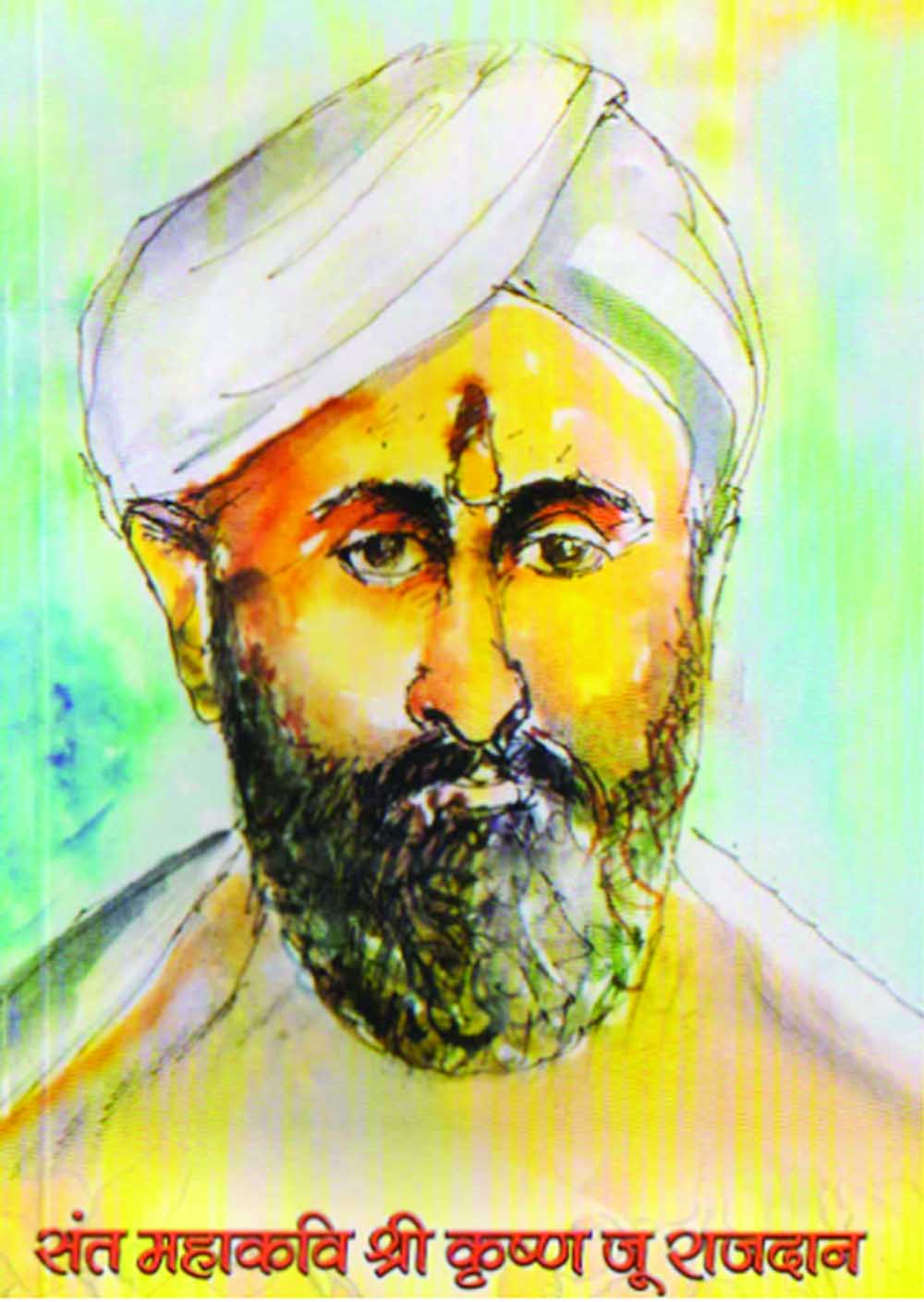

The Rishis, who are now being referred to as Sufis, even though Muslims, followed the principles of Reshut or call it Kashmiri Sufism. They were humanitarians, philosophers, psychologists and much more; but certainly not fundamentalists or religious bigots. Kashmiri Muslim poets like Sheikh Noor-ud-din, Rahman Dar, Abdul Ahad Zargar, Shamas Faqir, Wahab Khar, and many others practiced and wrote about advaita and sang praise of God. They were mystics concerned only with inner experience of reality even as they believed that all the religions at the top are mutually compatible. Among others, Swami Parmanand and Pandit Krishna JooRazdan were a part of the Bhakti movement and wrote devotional poetry of very high order along with the poets from the rest of India during 19th and 20th centuries.

Kashmiri Bhaktipoetry of the 19th century, or Lila poetry as it is more commonly called, touches its highest watermark in the spirituality-soaked lyrics of Krishna jooRazdan. What makes him stand apart from other Kashmiri Bhakti poets of the age, or poets belonging to other literary traditions for that matter, is his highly developed sense of music and his unusual concern for acoustic values. In no other Kashmiri poet’s work do we find poetry and music so intimately blended and used with such tremendous effect.

But it is not just the magic of verbal music, the “melodious lucidity” of his poems, so to say, that makes Krishna JooRazdan the great saint-poet that he was.

It is in the way the saint and the poet in him fuse with each other and find expression in his lyrical outpourings -sweet, lucid, musical–that the secret of his greatness lies.

Krishna joo Razdan and his great predecessors Paramanand and Prakashram Kurigami gave Kashmiri Bhakti poetry new dimensions, making it reflective of the true genius of the Kashmiri language.

The significance of the quintessential Kashmiriness of these poets can hardly be missed, for in their times the influence of Persian on Kashmiri language and literature had become so pervasive that Kashmir’s own literary tradition seemed to have lost its importance and relevance.

However, Krishna joo Razdan could and did succeed in bringing back some of the original glow and colloquial charm of the Kashmiri language by choosing the Bhakti experience rooted in the tradition of Kashmiri spirituality as the theme of his poetry.

Krishna Joorevived the long lost contacts between Kashmiri poetry and the perennial mainstream of Indian literary tradition. But it is not as though the Bhakti wave rolled over and reached Kashmir for the first time in Krishna jooRazdan’s age. He emerged as a foremost representative of what can be called the second phase of the Bhakti upsurge in Kashmiri poetry, but the tradition started five hundred years before him with the celebrated Shaiva poetess Lalleshwari.

It must be noted that the saguna and nirguna as well as the Shaiva and Vaishnava currents of the Bhakti movement converge in Krishna Joo Razdan, who was free from all sectarian bias.

We find him directing his devotion and love towards both Shiva and Krishna in his verses like the great Maithili poet Vidyapati, both being his chosen deities.

And even while doing so, he identifies them with the Highest Reality, the nirguna brahma. He sees no incompatibility between his belief in a personal and determinate God and an impersonal view of reality.

Even while being at the pinnacle he would still covet bhakti and pray to God to give him the wealth of devotion; “Bhakti ditam, bhakti ditam; bhakti hunduydarbarditam”.