Anjan Roy

To talk of coincidence, ‘Geetanjali’ has got lucky for a second time in a hundred and ten years. In the first time, Rabindranath Tagore’s book of poetry, Geetanjali, won him a Nobel Prize in literature. Now, a century and more later, another Geetanjali, the Hindi writer of stories, is awarded the hugely prestigious International Booker Prize for literature.

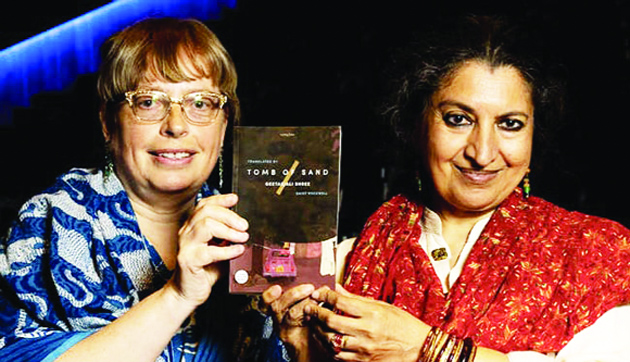

Geetanjali Shree’s story book, Ret Samadhi, translated as “Tomb of Sand” by the American translator Daisy Rockwell, has been described as a masterclass in exploring the nuances of life in a typical Indian family, of relations between people of different ages, young an old, of between males and females, against the background of a vast country going through a wrenching political transformation.

Her story is woven around a typical reality of an aged Indian lady of a large Indian family who suddenly gains the freedom of her life after the death of her husband. This reality is not an unknown in an Indian family of the sub-continent. Geetanjali Shree, born in Uttar Pradesh in 1957, could not have been insensitive to these turns and twists in a family’s life.

Geetanjali’s original Hindi was translated into English by Rockwell, who will share the prize money with the author. The total prize money is fifty thousand pound sterling. While talking of her translation, Rockwell admitted it was a difficult task given the subtle ways in which Geetanali has used the language to carry forward her narration.

Derided and condemned as bastion of obscurantism of a casteist traditionalist society, yet Geetanjali’s depiction of an Uttar Pradesh household possibly captures the quintessential elements of the Indian reality. The ecstasies as well as the tragedies in that reality is what lightens up the entire narrative of this sub-continent.

The International Booker Prize is different from the Booker Prize. The former is an award for books written in English and published in Britain. The former is one for books written in languages other than English and translated into English and published in Britain.

This is the first time that a subcontinental author is winning the International Booker Prize, unlike the Booker Prize in Literature which has been claimed by a number of Indian authors such as Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, Kiran Desai, Arvind Adiga for their novels written in English.

Announcing the award, the chair of the judges of International Booker Prize, Frank Wynne has observed: “This is a luminous novel of India and partition, but one whose spellbinding brio and fierce compassion weaves youth and age, male and female, family and nation into a kaleidoscopic whole”.

The core human elements apart, the background is also critical for the transcending appeal of Geetanjali’s novel. That is the partition of the country seventy five years back and the persisting social agonies of that cruel episode.

Simply stated, even after a gap of so many years, we have not managed to forget and totally overcome it.

Partition comes as a psychosis in sensitive minds and creeps into the dialogues. That it touches a raw core is why it comes into the conversation and why a novel by a modern woman would still reverberate with those muted sounds of long ago.

Even as late as 1938, barely ten years before the country was cut up, serious efforts were being made to avoid the catastrophe. As the Congress President, Subhas Chandra Bose had offered to Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the first prime ministership of undivided India.

Shortly thereafter, Subhas Bose was driven out from the post of Congress presidentship by Gandhi and Jinnah refused to have any dealings with that “old, wily fox”, that is, Gandhi.

Like the inevitable destruction of the dramatis personnae of Greek tragedies, it did not take long for Jinnah’s total disillusionment. He had become uncomfortable with the idea of Pakistan.

In his last days, Jinnah had reportedly written a personal letter to the Indian prime minister if he could be allowed to live in his dear home in Bombay. His wish remained unfulfilled in his dying days, which were not long in coming.

But consider it. What irresponsible, insensitive, self-serving the actions of the politicians were. Millions died, were made homeless, generations were traumatised and disinherited for the whims of the handful leaders.

Seventy five years later, that now looks to have been a wasted effort, like Russia’s Ukraine war today.

Is that the ultimate inevitability of history that mankind should continue committing foibles every now and then.

Mankind’s story is a tomb of sand. (IPA)

Trending Now

E-Paper