Aryan Gandral

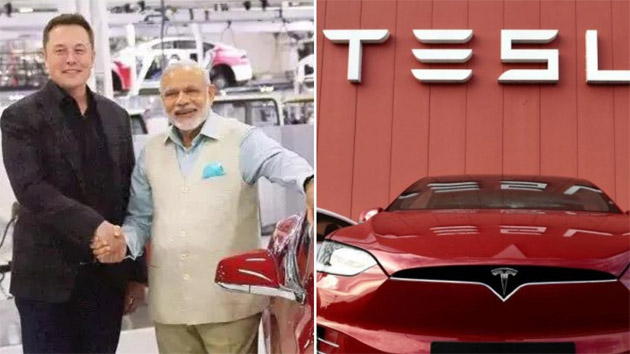

The India of the 1990s fondly remembers the emotions attached to the “people’s car” in the form of the Maruti Suzuki 800; it represented the aspirations of the developing Indian nation led by its growing middle class. Can a similar moment be associated with the interest shown by Elon Musk and his Tesla in stepping foot in India? A policy struggle between Musk’s assertion of a reduction of the 100 percent import duty on electric vehicles (EV) and the Indian Government’s condition for local manufacturing commitments by the global giant has come to an end with the New EV Policy of 2024. The policy entails a reduction of import duty to around 15 percent on EVs up to $35,000. But with conditions that include $500 million worth of investments, it is a win-win for both. Through this policy, the Government aims for three goals: environmental protection, saving foreign exchange, and job creation. First, India’s climate goals include a net zero by 2070 and a 50 percent reliance on renewable energy by 2030. By becoming a part of the global EV30@30 campaign, we intend to raise the share of EVs to 30 percent in our transportation sector from the present 2 percent. Second, India presently imports 85 percent of its petroleum needs; this not only leads to a drain of forex but also exposes us to external shocks like the recent Ukraine war, the West Asian conflict, and cartelization by OPEC. EVs promise a post-petroleum India. Third, as the economic survey of 2023 says, the EV sector can create 5 crore direct and indirect jobs in the next seven years. Like Maruti Suzuki overturned the fortunes of Gurgaon from a barren village to a major industrial hub, the potential of EV manufacturing and export is manifold given the “China +1.” Apart from Tesla, even Vietnamese companies like Vinfast have shown interest. The third-largest automobile market in the world is ready to embrace the EV revolution.

The Modi Government deserves major credit for its enabling policies in this regard. The subsidies under FAME, PLI, and import duty exemption on capital goods may be invisible to the public at large, but with a GST reduction to 5 percent, a road tax waiver, and the target of the power ministry to establish 22,000 charging stations alongside petrol pumps on national highways, these are major incentives for the public to transition. But rarely do revolutions come without roadblocks. The cheapest car sold by Tesla in the USA costs $400,000. Will it be able to produce an affordable car for the Indian market? As per news reports, after the Government refused to allow China-made Tesla into India, the company has decided to produce special right-hand side driving cars for India in its German factory. Another factor is the rise of Chinese BYD Auto, which is set to replace Tesla as the global leader in the EV space. With EVs as cheap as $15,000 and state-supported production, will Tesla be able to maintain its position? Similarly, whether the Indian Government will allow the Chinese company to enter our market is a question of the future. A larger policy question stems from domestic giants like Tata Motors, whose present EV share is over 70 percent. Some argue that, with import subsidies on a luxury product, domestic players are left in an unfair position. Should the Government support domestic industry or liberalize imports in an emerging tech revolution? This needs a wider discussion.

Another factor to look into is the share of two-wheelers in the EV sector. Companies like OLA and Bajaj have emerged as market leaders. Similar success in adoption needs to materialise in the four-wheeler segment. There are a few factors that are inhibiting this growth: A ‘range anxiety’ comes with EVs, as charging times of up to 10-12 hours give output worth 80-100 km. This is a cause of inconvenience. A major push by all levels of Government and industry is needed to expand the charging infrastructure.

Another is safety; the lithium-ion batteries that power the EVs are prone to fire accidents given their reactive and volatile nature. While the cool climate of Europe is desirable, further safety checks are necessary in tropical climates. Another question is: why should the public’s transition? There must be a behavioural change involving the techniques of social marketing. A feel-good factor, a feeling of contributing to a larger good, should be infused into the way EVs are positioned in the Indian market. This happened with the Swachh-Bharat Abhiyaan. Prime Minister Modi turned “cleanliness” into a national activity. Of course, buying a car involves lakhs of rupees, so it cannot be just an ’emotive appeal’.

The Government can initiate this by gradually replacing all its present vehicles with EVs. The private sector can take a clue from the IPL, in which EVs as a price are on show during each match. But most importantly, the public should make itself aware by making the right choices, given the example of Delhi’s polluted atmosphere in front of us. At the same time, the Government should move away from coal-powered energy plants to renewable sources like solar energy, as without it, there is only emission shifting and no reduction. The electricity powering an EV should be green. Further, this should not stop at EVs, but a wider expansion of CNG vehicles and the adoption of newer technology like ‘Green Hydrogen’ should be part of this national mission. The goal is to make India a developed country by 2047; development will come through jobs, exports, and climate safety. The coming of Tesla is just the beginning. It is a mission that involves the Government, industry, and the public at large.

Trending Now

E-Paper