Suman K Sharma

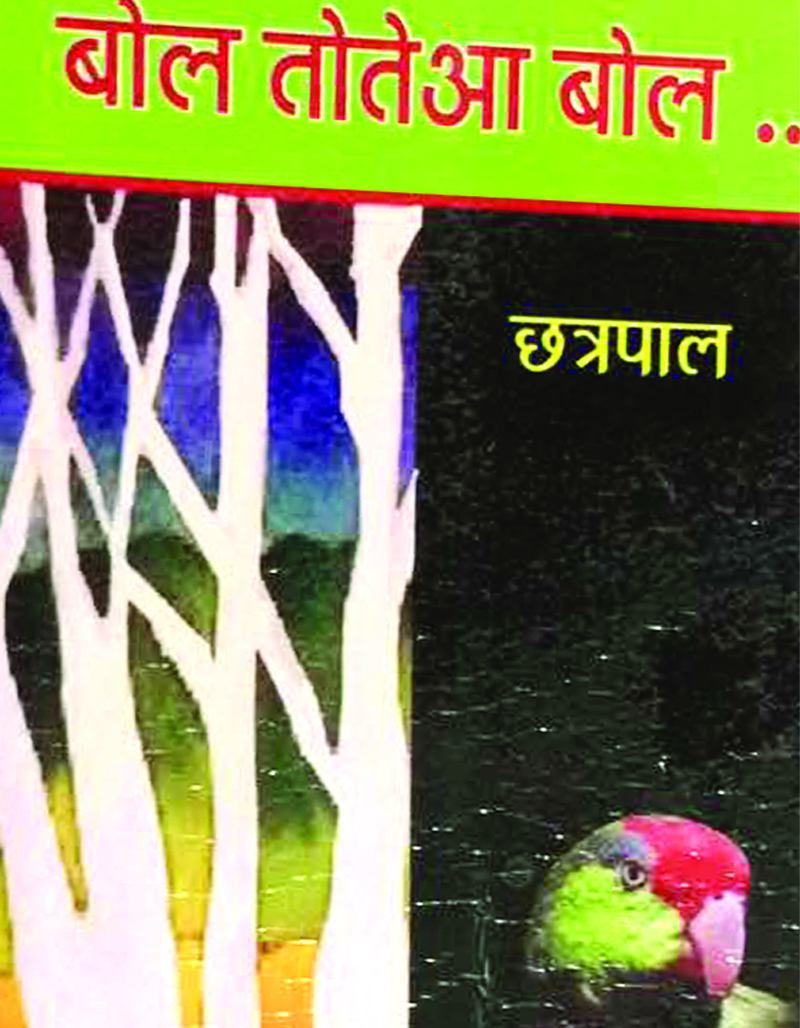

Chhattrapal, an accomplished Dogri writer, has come out with one more seminal work, Bol Toteya Bol (Dogri Sanstha, Jammu, 2016, 119 pages, Rs 300/-), a collection of 18 pieces of prickly prose, satirising our life and times. The narrative runs rather like the pillow talk of a particularly acerbic couple, apparently devoid of any structure, yet inciting one to sit up and take notice of what is wrong with us. Citing HarishankarParsai, Chhattrapal holds, ‘(Satire lies)… more in spirit than in structure. It is a characteristic inherent in all the genres (of writing), even though it adheres to none of them. The objective of satire is to carry the emotion. (This)…can be achieved through any of the genres….'(Introduction).

Chhattrapal achieves his objective by adopting the folk artefact of Tota-Mynastories. The eighteen chapters are on diverse aspects of corruption. In each chapter (the author adopts the term ‘katth’ for it), Tota, garrulous and worldly-wise as ever, engages his equally loquacious spouse,Myna, in a pungent dialogue on a chosen topic, and thereby hangs a tale.

The tone is set in the first katthitself, aptly titled, YathaParja, Tatha Raja – Likethe populace; like the king. Note the inversion of the ancient axiom ‘yatha raja, tathapraja’. By this device alone, the author has conveyed the bitter truth. The story goes like this: In a jungle, Lion-the-King holds a council to choose his ministers from amongst the representatives of the habitants. As one delegate after the other harps about his or her viciousness, our protagonist,Tota,his throat choked with emotion, cries out in disgust, ‘How can a sick hen lay a healthy egg (p.16)?’

It is a given that a sick society cannot throw up upright leaders. What is to be done then? The author seems to suggest in the concluding katth, J’gaa (Wake them Up!), that it is time somebody revived affinity in Jammuwalas for their past heroes. Discarding Tota’s persona, the all-knowing narrator himself speaks out: ‘Myna and Tota were much disappointed. They had tried to bring back,through the statues that adorn the squares of Jammu, some warmth in the masses for the old heroes like Raja Jambulochan, Miyan Dido, Maharaja Ranbir Singh, General Zorawar Singh, PanditPremNathDogra, Maharaja Hari Singh, General Bikram Singh, Brigadier Rajendra Singh, Girdhari Lala Dogra…., but felt that the perceptionof the people of Jammu lies buried under the Siachin Glacier (p.119).’

One may or may not agree with the author’s ready solution to the multitudinous problems that confront Jammu, but he surely has taken a swipe at them. Be it the callousness of the police (Kash Men Kutta Honda – If Only I Were A Dog) or the flourishing tribe of the corrupt (Gujjkhor – The Bribe-takers); the rising militancy in apusillanimous state (DaangBapu Di – The Bapu’s Staff) or thefratricidal power-mongers (Nikka Pappu, BaddaPappu -Pappu Junior and Pappu Senior); the spoiling of the river Tawi (TawiteDevak- The Tawi and the Devak) or the dereliction of the elderly (PeerhidarPeerhi- Generation after Generation) – hardly any blot or blemish on the face of once-proud Duggar has escaped his sharp scrutiny.

Chhattrapal is a veritable wordsmith. Putting together words of everyday use, he crafts expressions all his own. How about Maaskhor and Saagkhor for the carnivorous beasts and the herbivores? Or a Santra cabinet for an orange-like council of ministers that looks one from the outside but in reality is firmly divided? And see how Totareports Crow’s elevation to the Cabinet: ‘Owl, Secretary to Lion-the-King, looked quizzically at His Majesty and Lion in turn looked at the Old Lioness who sat behind a curtain. Lioness lifted her paw in assent and Crow’s name was inserted in the list of ministers (p.15).’ A rib-tickling take on a previous Government!

The author has sparsely, if at all, used irony to spice up BolToteya Bol. His anthropomorphising of the parrot-myna pair also goes to the extreme at places. In the katthManukkhenshaBacho(Keep Away From Mankind), page 56, Myna, while lambasting Tota for what she thinks is his misogyny, reminds him that he too is born of a woman! And by the time he reaches the last of the katths, J’gaa,Chhattrapal becomes pedagogical. Despite these glitches, his stings and barbs remain intact.