Dr R L Bhat

Lovelorn kissed the floret-footed

And, kindled the dreams nigh,

The fiery flare, seeing it all

Gave out a long drawn sigh.

Feeling flower on a forlorn twig,

Came visiting its hopes again:

The snow is melting and, perchance,

The spring may be here, again!

Jagan Nath Sagar, the poet of this rich tapestry, had nature virtually in his lap. Living literally under the feet of Kshiir Bhavaanii, Manzgam, short miles from Aharbal, the singular cascade of Kashmir, at the feet of the lore-full Kramasar (Koonsarnaag Lake), the scented Kongu’wattan almost within smelling range, he envisions nature and paints it on a paper canvas with words…oh, so sweetly! When he mixes it with his poetic sensibility he produce a richness which imbibes nature lapful after lapful. Nazm, especially the nature poetry, is his forte. And, why not. He needed only to open his eye to find nature impinging upon him. Just taking a pen along, and recording the communions could turn ordinary persons into poets. But here was a poet observing nature, experiencing and envisioning it with inspiration. That record is now before us in the form of Sagar’s book of verses Paaru’dy Tsih, ‘the Mercurial Moments’. (Kashmiri text and words are in RRK, the “Rationalized Roman for Kashmiri” modification devised by RLB.)

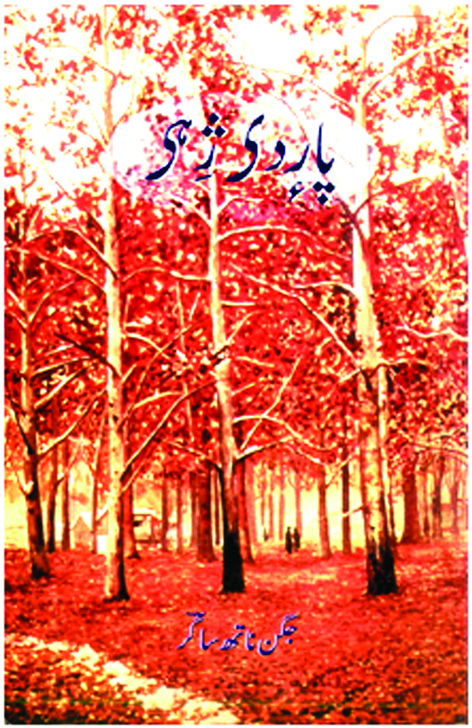

Paaru’dy Tsih comes wrapped in the red haze of leaves falling off naked chinars standing untrammeled in their marble whiteness. That symbolizes the offering from Sagar, in poesy over half a century, rather well. Sagar says he published his first book of verse Nov Partav in 1961. Paaru’dy Tsih comes after long decades and, presumably, presents his own selections of the four decades. This book is divided into two section – Nazm and Gazl. The two genres are antithesis of each other. Nazm, they say, tests a poet’s accomplishment. Sagar’s Nazm certainly lands him a respectable place in Kashmiri Nazm. He not only treads the beaten path rather well, but also transcends it.

Samai chhu almaas mokhu’me moonum,…….

the time, I agree, is poison- faced,

hope, alone, enlivens the flame;

it maketh this our day worthy,

for, of it is the marrow born!

The focused nature of Nazm allows it to be used for a variety of purposes. Reform, instruction, hits and misses of life, helpless wonderment at boisterous nature, dismay frustrations…. And, an enlivening hope … all can be portrayed here without the compulsion of transience distracting the poet. Sagar hands down elderly advice, giving intimations of deep experience.

Sagar’s native village Manzgam forms with Tulamula and Raithan, the third place of Kshiir Bhawaani pilgrimage in Kashmir valley. Kshiir Bhawani Manzgam is situated atop a hillock completing what was not so long ago a thick forest. As Sagar adds, the Qayaamudiin’s Ziarat has been erected just apposite. Sagar’s ‘Tsandankul’ sings of the famous chandan-tree in this forest which, it is said, becomes invisible the moment one reaches it. Sagar pens a short “daryaav-like” poem around this tree. Another specialty of the area, Sagar talks of is Ddal masala a dish of whole grains of wheat, maize, beans, boiled together and spiced hot, which was eaten of particularly chilly winter-days.

Maj khavem ddal Masaalaa….

May be it’s snowed by morn,

We’ll have enjoyment free

Mother’ll serve ddal masaalaa,

fatigue’ll vanish, oh what joy!

The poem shiinu’ petoo (Fall, snow fall!) is an intimation of the hard life of winter. Kashmir winter, especially of the days our poet writes of, was much harder. It is a superb description of this life, its joys and hardships, especially how people made a lot of small mercies like a hot cup of tea after a particularly shiver-some chill.

The second part of book is gazls. Sagar’s gazl is gazal in the true Persio-Urdu tradition. Kashmiri Gazl, has had a long wrangle with verse-form Vatsun which is the indigenous Kashmiri genre for the poetry of love and romance. Vatsun is lively, truer and a lot closer to the warm Kashmiri usage and emotion. If Kaliimudiin Ahmad called gazl ‘a semi barbaric genre’, Vatsun is a sensuous distillation depicting love in exceeding sensitivity and feel. From Habba Khotuun and A’rnimaal to Miir and Mahjuur, the Kashmiri love poetry had been immortalised by this heartful sensuality. That may be the reason why major Kashmiri poets have unthinkingly reverted to vatsun when striving to write gazls under dictates of Persio-Urdu influence. Critics like Amiin Kaa’mil (Javaaban chhu arz) maintain that Kashmiri diction is impracticable of being truly moulded into Aruuz, the essential metric compulsion of gazl. Most sticklers after gazl have been decrying this “defect” in Kashmiri poets from Mahmuud Gaa’mii through Miir to present day poets (cf. Aktar Mohiidiin – Shiiraazu’ 1993 No. 5). Indeed, it is only recently that some Kashmiri poets have fully worn this alien cloak and, abandoning the pervasive tendency for original vatsun, have been writing “correct” gazl. The gazls in Paaru’dy Tsih confirm Sagar as a successful gazl writer. The ordained content and prescribed form, as well as the characteristic versatility, are all evident in Sagar.

Janoon ra’tsrith me thov choonuy amaanth

Madness I wore a gifted wreath

Janoon, I have preserved they keepsake;

Ba’ly beyan ilzaam khaarun chha ravaa

Vante sezi vati kus sanaa tas ddaalihee?

(Is it meet to blame others, Pray?

who’d have misled him, anyway?)

The classical beloved of gazl goes, rather has to go astry. That, indeed, is its true path. Now who could have led it away from its wonted path which, of course is away from the way normal worldly folks take!

Sagar is sublimating pain, throwing up reiterations of love and yet reminding all of the perfidy of humanism that came to be expressed there. Here he takes a definite step towards poetic excellence, towards hope, through universalisation of pain and pathos. Paru’dy Tsih, attests to this in Gazl as well as the Nazm parts. His poetic arriviste, his grip over language and finesse of feelings qualify him as a voice in Kashmiri literature that needs be heard, scrutinized for its truth, appreciated for its merit.

Trending Now

E-Paper