WASHINGTON: In a breakthrough, scientists have developed a new nanomaterial that uses solar energy to generate hydrogen from seawater, producing the low cost and clean-burning fuel more efficiently than existing materials.

The advance may lead to a new source of hydrogen fuel, ease demand for fossil fuels and boost the economy of countries where sunshine and seawater are abundant.

It is possible to produce hydrogen to power fuel cells by extracting the gas from seawater, but the electricity required to do it makes the process costly.

Researchers from University of Central Florida in the US developed a new catalyst that is able to not only harvest a much broader spectrum of light than other materials, but also stand up to the harsh conditions found in seawater.

“We’ve opened a new window to splitting real water, not just purified water in a lab. This really works well in seawater,” said Yang Yang, assistant professor at UCF.

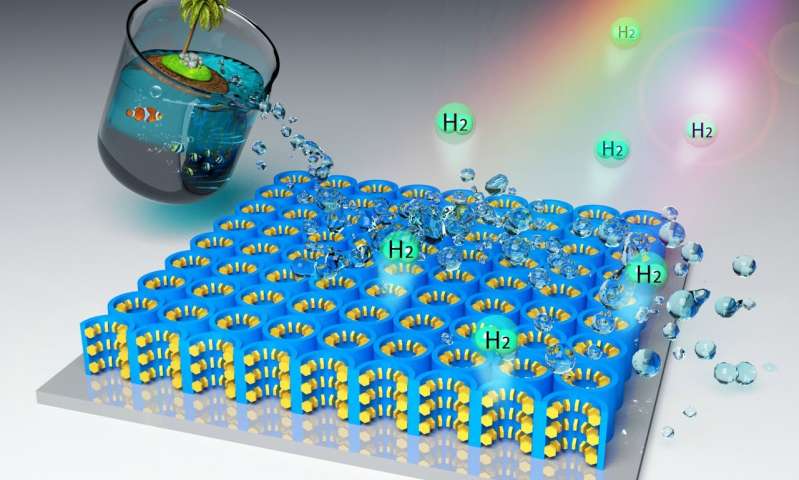

Yang developed a method of fabricating a photocatalyst composed of a hybrid material. Tiny nanocavities were chemically etched onto the surface of an ultrathin film of titanium dioxide, the most common photocatalyst.

Those nanocavity indentations were coated with nanoflakes of molybdenum disulfide, a two-dimensional material with the thickness of a single atom.

Typical catalysts are able to convert only a limited bandwidth of light to energy. With its new material, Yang’s team is able to significantly boost the bandwidth of light that can be harvested.

By controlling the density of sulphur vacancy within the nanoflakes, they can produce energy from ultraviolet-visible to near-infrared light wavelengths, making it at least twice as efficient as current photocatalysts.

“We can absorb much more solar energy from the light than the conventional material,” Yang said.

In many situations, producing a chemical fuel from solar energy is a better solution than producing electricity from solar panels, he said.

That electricity must be used or stored in batteries, which degrade, while hydrogen gas is easily stored and transported.

Fabricating the catalyst is relatively easy and inexpensive. Researchers are now trying to find the best way to scale up the fabrication, and further improve its performance so that it is possible to split hydrogen from wastewater. (AGENCIES)

Trending Now

E-Paper