Chaitanya Basotra

Nestled in the Himalayan foothills, lies a small and peaceful village called Jasrota. Situated in the Jammu region of the now UT of J&K, it was once home to a kingdom. Founded in 1064 AD, the Dogra principality is long gone. However, close to the village lies an old, decrepit structure eponymously called the ‘Jasrota Fort’.

All that remains of the once magnificent and towering structure is a collection of rocks, which some might call columns along with a generous growth of weed and shrubs all around. Even a google search would tell a curious mind that the fort has seen better days.

One might ask then, why is this fort even now relevant? Why is this small, once prosperous Dogra principality, even worth mentioning? Why do we even know about this place?

The answer to all three questions would be – art – magnificent art at that.What is interesting about this once independent state is that it was not immortalised by its warriors or by its kings, but rather, by one painter, who some call “one of the most original and brilliant of Indian painters”. The British painter, Howard Hodgkin called him, “the first great modern artist of India”. This extraordinary genius was a man called Nainsukh or “joy to the eyes”. A painter who came from a tradition that was centuries old, yet imbibed it and gave it a new course.

At Guler

Born in 1710, in the hill principality of Guler, he was exposed to Mughal and Pahari Art forms, from a very young age. Both his father and brothers schooled him in the Pahari traditions of northern India. As noted by Sunil Khilnani in Incarnations: India in 50 Lives, “It is a tradition characterized by simplified landscape and interiors, flat monochromatic backgrounds and in the foreground stylised, often quite static portraiture”.

Born in 1710, in the hill principality of Guler, he was exposed to Mughal and Pahari Art forms, from a very young age. Both his father and brothers schooled him in the Pahari traditions of northern India. As noted by Sunil Khilnani in Incarnations: India in 50 Lives, “It is a tradition characterized by simplified landscape and interiors, flat monochromatic backgrounds and in the foreground stylised, often quite static portraiture”.

The environs in which Nainsukh found himself proved to be fertile ground in which were sown the seeds of artistic balance and virtuosity. In fact, his elder brother Manaku proved to be another skilled practitioner and exponent of the Pahari art form.

However, it must be mentioned that this was a time of evolution in the realm of Pahari art, as well. A stasis of convention on the one hand and dynamism of the modern and the new on the other, was grasped at by Naisukh with both hands. Eventually leading to further experimentation which created a synthesis of the two.

We get a glimpse of the physical makeup of the painter as well as the inspirations which drew his brush, from the self portrait he drew at the age of 20, while still at Guler. It shows a “lean face with a thin mustache and a neatly shaven head with just a tuft of hair under a turban, rather visible front teeth too. Accuracy is far more important to him than vanity. His left hand supports the takhti, the wooden drawing board, and his right hand holds a brush housed above blank paper just at the moment of beginning to draw. His expression is intent as though he is fixing an image in his mind”.

Finding his “muse” – Jasrota

It is not known why but in 1740, he left Guler for the hill principality of Jasrota, possibly looking for a new patron. Here at Jasrota, he worked for various patrons, the most important being Raja Balwant Singh, the local ruler. Sunil Khilnani calls the Raja, Nainsukh’s muse, metaphorically speaking of course. The cause of this metaphor, however, is well founded. Nainsukh drew copious amounts of artworks depicting the Raja.

An overview of his work there

His first paintings were drawn with the restraint of traditional attributes of the pahari style. This however changed as time passed. He started experimenting with “restrained use of colour and his celebration of black and white space and above all in how he represented his patron”.

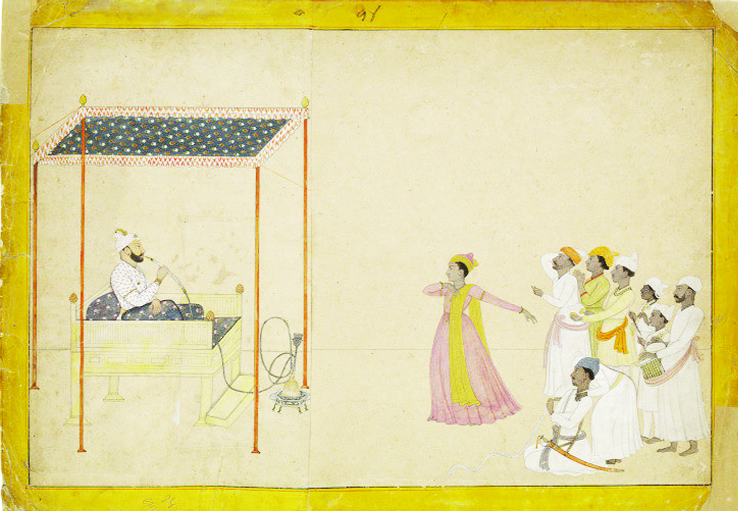

The Raja is depicted getting his beard trimmed, writing a letter, performing a Puja, smoking a hookah and inspecting a painting. Nainsukh puts forth an almost modern “instagramesque familiarity” when he paints his patron being mimicked by a performer. In one scenario he is painted huddled under a blanket depressed and in another, writing a “letter bare chested in his tent while his attendant fly whisk in hand has dosed off in the hot afternoon”.

The Raja is depicted getting his beard trimmed, writing a letter, performing a Puja, smoking a hookah and inspecting a painting. Nainsukh puts forth an almost modern “instagramesque familiarity” when he paints his patron being mimicked by a performer. In one scenario he is painted huddled under a blanket depressed and in another, writing a “letter bare chested in his tent while his attendant fly whisk in hand has dosed off in the hot afternoon”.

B.N. Goswamy, one of the leading art historians of India, points out that Nainsukh in more ways than one “attached” himself with this raja. In his words, “he [Nainsukh] is like a shadow of the Raja, maybe he[the raja] is the shadow of Nainsukh, and he has no troubles in showing that and nor does Balwant Singh have a problem with this”. According to Goswamy, here is a painter, who “recorded” things which no one in the Indian context, before him, did.

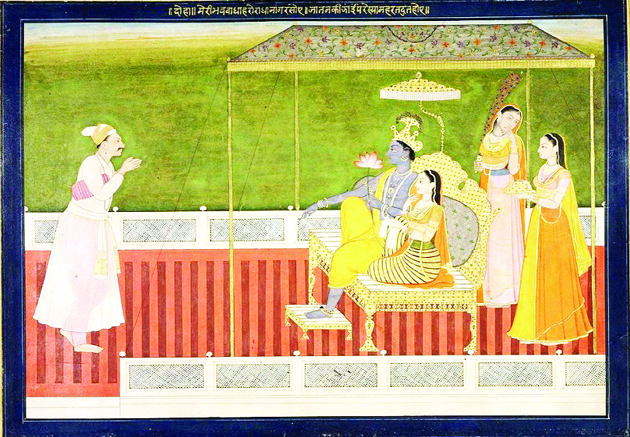

Raja Balwant Singh watches performers

Khilnani points out V.S. Naipaul’s criticism of Indians that “they don’t see what’s around them”. But, Nainsukh saw plenty. He saw not just the comedy, that is the grand facade of courtly life, but also saw the nuances and textures that variegate across the domestic life of an individual.

In one of his paintings, currently at the Victoria Albert Museum in London, Balwant Singh is seen watching the performance of a group of dancers and musicians. Nainsukh, though, does not leave his description of this scene just to a few dancers. He adds to the humanity of the scene by depicting a man mimicking the raja with a hookah made of paper in his hands.

What is even more interesting about the painting is something you would need a magnifying glass to see. The lead singer, wearing an orange turban, “has marks of smallpox on his hands” and this immediately takes you to the world that Nainsukh occupied, the people he intermingled with and the friends and companions he made.

Nainsukh’s Final Years and Basohli

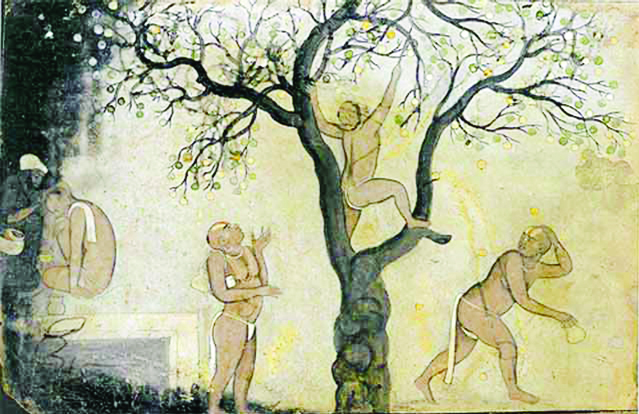

After the demise of his patron, Nainsukh left Jasrota for the hill principality of Basohli in 1763. Here we see the Ruler, Raja Amrit Pal, leaving an indelible mark on what the artist was to produce. Instead of scenes from everyday life, Nainsukh was painting about scenes and stories from the Indian Epics, grounded in a frame extricated from the experimentation which besought his more interesting works in Jasrota.

You see the dark colours giving way to brighter ones. You see vivid shades of green all around, but you also see subtlety giving way to a certain sense of glibness. Although Nainsukh was still able to produce a masterpiece, it was quite evident that Jasrota was now in the past.

The paintings, which may be termed of the ‘Basohli period’, are incongruous with the creative stasis they undergo, due to the way in which shadows are used by Nainsukh. This is what B.N. Goswamy says about a night scene painted by Nainsukh:

“The way his studies reflect reflections and, you know, how shadows fall, it’s extraordinary and it’s a unique painting in the whole range of Indian art. There are people who did night scenes, but this is not a night scene as such. This is his way of telling you that this is how light falls. He does it so extraordinarily subtly, and subtlety is the[his] sense”.

His Art – The Wealth of the Dogras

The world of the Dogras, royal and common both, comes alive in the artistic expressions of Nainsukh. There is a dearth of literature on not just the ancient but also the medieval history of the Dogras. Justice Gajendragadkar in his report of 1968, stated that the history of the Dogra people before that of the coming of Ranjit Dev remains a fiduciary of a “hoary past”.

In Nainsukh’s paintings, however, we see the cultural life of the Dogras in the 18th century coming to full bloom. ‘Our’ painter was a contemporary of the great Raja Ranjit Dev and even though various scholarly works on him have been written, for example by Professor Sukhdev Singh Charak, I always wondered what life in the Jammu hills at that time would have looked like, felt like, seemed like.

In Nainsukh’s paintings, however, we see the cultural life of the Dogras in the 18th century coming to full bloom. ‘Our’ painter was a contemporary of the great Raja Ranjit Dev and even though various scholarly works on him have been written, for example by Professor Sukhdev Singh Charak, I always wondered what life in the Jammu hills at that time would have looked like, felt like, seemed like.

As a Dogra therefore, Nainsukh’s paintings are an eternal source of pride and cherishment to me. In his paintings lie the traces of our glorious past, an homage to what we were, rather how we were as people. How the Dogras looked, how they dressed, how they laughed, how they sang, how they listened but most importantly, how they painted.

Conclusion

This is how Sunil Khilnani begins his episode on Nainsukh:

“There is a game you can start to play after looking at hundreds of Indian miniature paintings – call it Mughal miniature bingo. Is there a prince with a very straight back – check. Pavilions – check. Musicians, gathered courtiers, glorious gardens – check, check, check. Game over”.

This is how most Indian miniature paintings were like. They were in many ways “press releases” for their patrons and for their kings. In the paintings of Bichitr, Manohar and Abul’ Hassan, this becomes all the more true.

In Bichitr’s depiction of Shah Jahan receiving his three sons (Shahnama plate 10), you see a rich, almost blindingly confusing, intermeshing of colour, shape and form. The human sensibility is given way to the more politically rewarding act of depicting imperial splendour.

This is where the painter under our consideration, departs from these other giants of the miniaturist tradition. Here is a painter whose works are incredibly human, entrenched with etchings of the human soul and the human struggle around existence. He is special because he shows that it is possible to “pay homage to the tradition you have come from, the classical, and then to break free”. The “extraordinary precision of his lines, and his bold use of blank space” make him a legendary practitioner of his craft.

Amit Dutta in his 2010 film complements the genius of Nainsukh by infusing it with the instruments of modern cinema. The movie is shot in the midst of the ruins of Jasrota Fort and, in the environs of these ruins, Dutta recreates and reimagines the contours of these pahari paintings through light, camera, sound and direction.

The gentle yet swift flow of a river, the dance strokes of a courtesan, the shouting of men in a hunt are all depicted with the same alacrity and consciousness of the human condition, which Nainsukh conveys through his paintings.

A lot of other things can be said about this great artist, but I will limit my position on the man to this – the Romantic poet Shelley talks about the temporariness of kings and civilisations in his poem ‘Ozymandias’, but here is a man who pulls out this tiny principality in the Himalayas from obscurity and immortalises it through the power of his brush and imagination.