WASHINGTON: Scientists have designed a novel ‘metallic wood’ that is stronger, but at least four times lighter, than titanium.

High-performance golf clubs and airplane wings are made out of titanium, which is as strong as steel but about twice as light.

These properties depend on the way a metal’s atoms are stacked, but random defects that arise in the manufacturing process mean that these materials are only a fraction as strong as they could theoretically be.

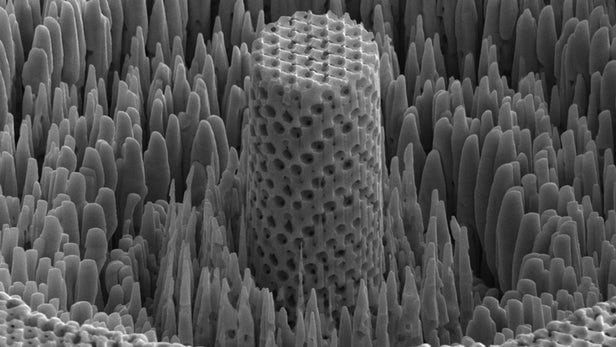

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania in the US and the University of Cambridge in the UK have built a sheet of nickel with nanoscale pores that make it as strong as titanium but four to five times lighter.

The empty space of the pores, and the self-assembly process in which they are made, make the porous metal akin to a natural material, such as wood.

Just as the porosity of wood grain serves the biological function of transporting energy, the empty space in the researchers’ “metallic wood” could be infused with other materials.

Infusing the scaffolding with anode and cathode materials would enable this metallic wood to serve double duty: a plane wing or prosthetic leg that is also a battery, researchers said.

“The reason we call it metallic wood is not just its density, which is about that of wood, but its cellular nature,” said James Pikul, an assistant professor at University of Pennsylvania.

“We have areas that are thick and dense with strong metal struts, and areas that are porous with air gaps. We’re just operating at the length scales where the strength of struts approaches the theoretical maximum,” Pikul said.

The struts in the researchers’ metallic wood are around 10 nanometres wide, or about 100 nickel atoms across. Other approaches involve using 3D-printing-like techniques to make nanoscale scaffoldings with hundred-nanometre precision, but the slow and painstaking process is hard to scale to useful sizes.

“We’ve known that going smaller gets you stronger for some time, but people haven’t been able to make these structures with strong materials that are big enough that you’d be able to do something useful,” Pikul said.

“Most examples made from strong materials have been about the size of a small flea, but with our approach, we can make metallic wood samples that are 400 times larger,” he said.

Replicating the production process at commercially relevant sizes is the team’s next challenge. Unlike titanium, none of the materials used by the researchers are particularly rare or expensive on their own, but the infrastructure necessary for working with them on the nanoscale is currently limited.

Once that infrastructure is developed, economies of scale should make producing meaningful quantities of metallic wood faster and less expensive, researchers said.

Once the researchers can produce samples of their metallic wood in larger sizes, they can begin subjecting it to more macroscale tests. A better understanding of its tensile properties, for example, is critical. (AGENCIES)