Ansh Chowdhari

This relationship was unique, perhaps ironic on many fronts but that nonetheless represented the tides of yore in which some characters were intermingling cutting across their personas for an association that was impractical and unwelcome. I’m referring to the relationship that Maharaja Hari Singh shared with his lead court singer Malka Pukhraj. The prime source of this relationship happens to be Pukhraj’s autobiography Song Sung True that I was able to obtain a few weeks ago from the JNU library. This bona fide chemistry was the highlight of the book that narrated the life experience of the author at the Dogra court of J&K.

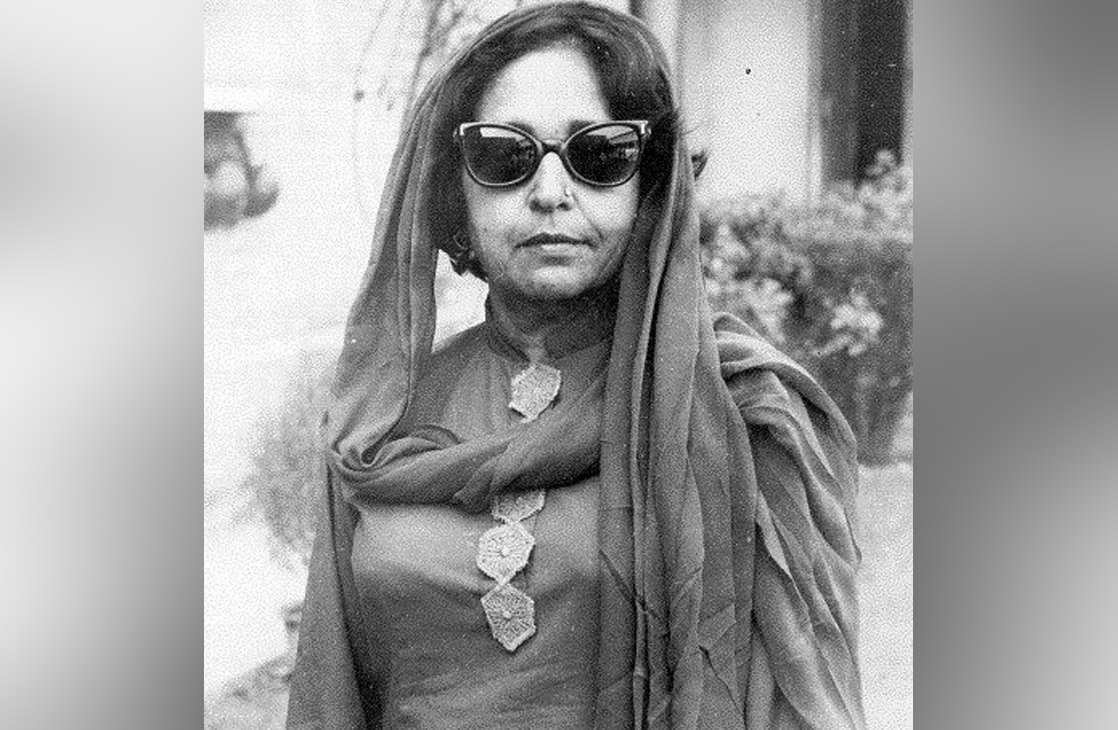

Coming from a modest yet conservative Muslim family of Akhnoor Pukhraj’s rise to become a much-adored part of Maharaja’s Durbar was something that she owned, and occasionally gloats about profusely. Her unrequited ‘love’ for the man sitting on the throne governing the largest princely state of the country gets exhibited time and again in her memoir. Their deep affectionate bond was surpassing the boundaries of caste, religion and royal etiquettes. She wasn’t confined to the chequered gender realities of a middle-class Muslim women of those times that anchored in them being as good wives and daughters. For example, Pukhraj in the frontispiece of her book says, “dedicated to the memory of my husband Syed Shabbir Hussain shah and Maharaja Hari Singh the last ruler of Jammu and Kashmir”. This was indeed a daring venture on her side to place a long-forgotten master of hers at the same pedestal as her husband. The intermingling of their respective personalities created a zone of confluence which no one dared to enter or occupy. This got more interesting as she narrates her anecdotal stories throughout the book, where her respect for the sovereign and disdain for his critics come across quite explicitly.

There’s a tinge of ebullience in her writing while mentioning and narrating Maharaja’s virtues. She narrates that during the coronation ceremony many Nawabs and Maharajas had graced the occasion, but, as per her “of the Maharajas, it was only our Maharaja and the Maharaja of Patiala who could carry off their grand costumes and jewellery and who looked like real maharajas.”….Her attention to detail in the book vis a vis scores of events is acute and sharp. Apparently, the Maharaja is the central character of her entire tenure as the court singer, wherein, she doesn’t want to share that space with anyone, howsoever talented or not. It gets cleared in an event where she regretfully accepts her mistake of introducing another singer to the Maharaja who had started ingratiating herself with the latter, despite former’s protestations. Malka Pukhraj’s connection to the court is primarily because of that association with the ruler.

The fine thread holding that relationship intact was constantly under pressure due to court machinations of all sorts. Pukhraj is quite rustic of her behaviour and makes no qualms about being vindictive at times for the sake of her master who was the cynosure of her entire existence. Everything else apart from the Maharaja is of no relevance to her. Their power dynamic was much beyond the usual understanding of an employee-employer relationship. The power was not just plainly vertical but diffused and proliferated. At times, Malka is seen making herself heard by arguing with probably the richest and most powerful man of the largest Indian state. She was not keen to take her master’s dictums at the face value. Her presence irked the ruling Rajputs as she was able to make herself close to the ruler at the expense of tailored power hierarchy. She was able to capture a seat for herself in Maharaja’s coterie, which was surprisingly superior to many courtiers in the hierarchy that prevailed at the court. This power structure anomaly was strikingly vivid in that set up where the ‘usual suspects’ were sidelined for an individual who represented the peripheral values at the court but arguably happens to be the closest friend to the ruler.

The changing political circumstances and the altered realities of states proved too fatal for this relationship. The court intrigues worked like venomous arrows that pierced the armour of their bond and created a mutual distrust of an order that was non-redeemable. Rumours of many hues that simulated the political scene of that time were agog which deepened the chasm. Her Muslim identity that earlier worked in her favour (singing bhajans in temples) in sync with the Maharaja’s reformative zeal now became her prime animus. She was ‘othered’ in the comity which accompanied the communal frenzy enveloping the state. Her leaving this state, apart from those personal reasons, were also influenced by that insecurity, not to mention the Maharajas indifference. The borders of the newly created dominions worked to sabotage the remaining admiration. The forlorn attempts to salvage the situation met the dead end. The situational realities demanded a separation that was complete yet unfulfilled. The love that once blossomed had dimmed. Mallika says “For many nights after I had withdrawn from the court, I thought of His Highness before I fell asleep….it was only after I had left him that I realized how attached I had become to him and how much I loved him I felt like going to Jammu and seeing him, to tell him that I wanted to live with him; that I could not live without him…I wrote him countless letters asking for permission to see him just once. I received no acknowledgement for any of those requests. He now hated me as much as he had once loved me…till today, to this very moment, I love him”

Mallika Pukhraj represents the eternal feminist quest of longing for her lover without any demand for reciprocity. Her innate sophistication gets a clear medium through this book where she, despite the conservative shroud that overhangs her upbringing, has disposed herself to express her raw desires, though implicitly, with much panache. With a consummate elegance Pukhraj has defined the romance of those times, not certainly in terms of any physical intimacy, but of the larger ecosystem set in the backdrop of Jammu and Kashmir where everything has been painted in vivid bright and bold colours. Pukhraj was a shrewd lady. She understands the nuance and dynamics of the politics in which she appears as a lawyer for the Maharaja many a time. The quagmire of this relationship has enamoured me to an extent that I couldn’t help but draw some parallels with some love stories of yore. Be that as it may, this story remained incomplete after “The Raj of Mallika Pukhraj” ended. Maharaja died in Bombay. Pukhraj writing after four decades after his death, perhaps was trying to give a last shot to her feelings that she had harboured in her heart ever since she met that man in early 1920s. It must have been a moment of solace for her, an apology, perhaps.

Trending Now

E-Paper