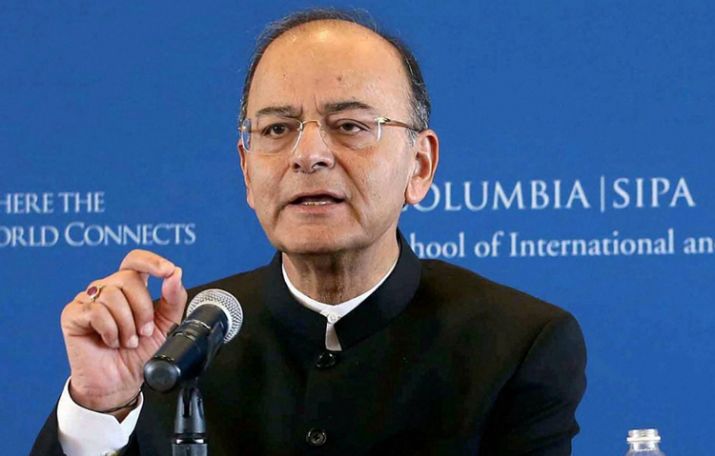

NEW DELHI: Union Minister Arun Jaitley today criticised the Congress party for creating hue and cry over the government’s decision to refer back a judicial appointment recommendation to the collegium for reconsideration.

He also recalled how the judges were superseded in the past and attempts were made to influence judgements.

The government had returned the recommendation of Supreme Court collegium for elevation of Uttarakhand High Court Chief Justice K M Joseph to the apex court. Although, the collegium has decided to resend his name to the government, it is yet to officially approach the government.

Under the present scenario, Jaitley said the executive can give inputs to the collegium, it can even refer a recommendation back with relevant inputs for reconsideration but is eventually bound by the recommendations. “This is contrary to the text of the Constitution,” he said in a Facebook post.

“The hue and cry made by my friends in the Congress party recently when the government referred a case back for reconsideration, fades into the oblivion.

“It is part of the much diluted role of an elected government that relevant inputs be brought to the notice of the collegium. This is in consonance with democratic accountability …? I have written this blog so that my friends in the Congress party get an opportunity to look at the mirror,” he said.

Jaitley spelled out various incidents of the past where judges of the Supreme Court were superseded and how recommendations of the apex court were turned down.

“Chief Justice Hidayatullah recommended the names of Justice S P Kotwal, the Chief Justice of Bombay; Justice M S Menon, Chief Justice of Kerala to the Supreme Court. The executive did not respond to either of the two names and ignored the recommendations. The Chief Justice meekly submitted and never questioned the inaction,” Jaitley said.

Citing the famous Kesavananda Bharati case, the minister recalled how the government of the day tried to subvert the independence of judiciary and gain the power to even tweak the basic tenets of the Constitution with the help of Parliament.

It was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court that outlined the basic structure doctrine of the constitution, which cannot be tempered with.

“It goes to (T R) Andhyarjuna’s credit that having appeared with H M Seervai on the government side, he has authored a brilliant and accurate day by day history of how the Kesavananda case proceeded. There was acrimony on the bench,” Jaitley said.

Andhyarjuna’s book, The Kesavananda Bharati Case – the Untold Story of Struggle for Supremacy by Supreme Court and Parliament, was published in 2011.

The citizen was represented by Nani Palkhiwala and the government by H M Seervai with supporting arguments from Attorney General Niren De, he said, recalling details from the book.

“When a judge asked counsel a question, someone with an alternate opinion on the bench would answer it. It was a thirteen judge bench and the obvious object of both sides in a dividing bench was to reach the figure of 7 for the law to be laid down. There are several interesting episodes which need to be stated,” he said.

He also recounted how the government tried various tricks to delay the hearing so that the then Chief Justice S M Sikri retires and government retains the right to amend the constitution even with regard to fundamental rights.

Finally on the judgement day, six judges held that fundamental rights were unamendable and there was an implied limitation on the power of Parliament to amend.

Six others held that Parliament had power to amend every Article of the Constitution, he said.

“The thirteenth judge H R Khanna held that the implied limitation on the power to amend was in relation to the basic structure of the constitution. The opinion of one judge thus became the law. After the judgement had been read and the Chief Justice read out the final order with regard to the law declared by the Supreme Court and then signed the same, he circulated it to the bench for signatures,” he said.

Four of the dissenting judges — A N Ray, M H Beg, K K Mathew and S N Dwivedi — refused to sign the order, he said, adding that the Kesavananda Bharati’s final order was signed by only nine of the thirteen judges.

That very day J M Shelat, A N Grover and K S Hegde were superseded and A N Ray become the new Chief Justice. Upon Ray’s retirement, H R Khanna was superseded and Beg became the Chief Justice, he said.

Talking about Nehru era, Jaitley said when Justice H J Kania started recommending names for appointment to the High Courts, it caused a significant flutter.

“Pandit Nehru questioned his suitability to be the first Chief Justice of India. It was only Sardar Patel’s pragmatism that had enabled him to manage Justice Kania,” he said. (AGENCIES)