Susharma

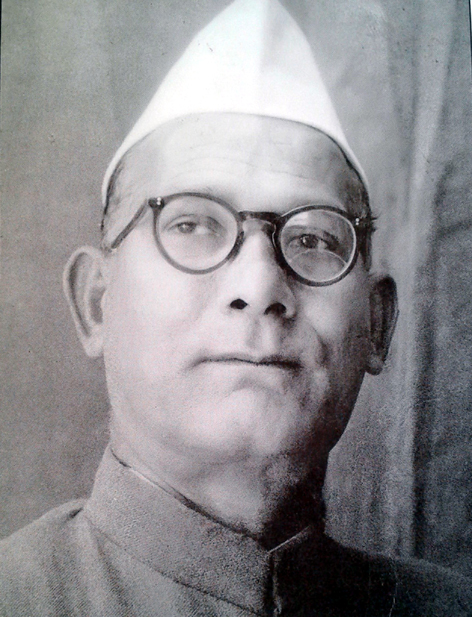

A distant look in bespectacled eyes and a determined chin on a square face showed the sort of man Lala Mulk Raj Saraf was – strong, resolute and a born fighter set upon achieving an objective which seemed beyond his reach.

Born on 8 April, 1894 in Samba, a township 40 km from Jammu, he was the fourth of Lala Daya Ram Saraf’s five sons. The family thrived on a drapery and general merchandise store that the senior Mr Saraf ran. Mulk Raj was nine when nearly whole of his family was wiped off in a plague epidemic, leaving him an orphan with one surviving brother, barely two years older to him. Mercifully, the two brothers were looked after by their paternal uncle, Lala Mangtu Shah. Adversity only brought out what was the best in him. He started going to school at the age of eleven. Being the oldest boy in his class, he did not mind fetching for his teachers a maund (over 37.3 kilograms) of vegetables all the way from Jammu. He had to cover that distance on foot in two days. Hauling burden for others at a considerable cost to his own comfort and wellbeing became a motto for the rest of his life.

In his BA final exam, an incident occurred that Mr Saraf in his old age recalled with a touch of pride. In the Economics Paper A, he thought he had misused the Exam Superintendent’s permission to make a minor change in his answer sheet by erasing instead a whole erroneous paragraph. To expiate his perceived sin, he sought out, in the curfew-bound Lahore Cantonment, the Superintendent, an Englishman, who was the principal of a missionary college of Lahore. (J&K state at that time did not have a university and the PoW College, Jammu was affiliated with the University of Punjab, Lahore). “Ask (H)is pardon, Who pardons us all,” the principal told him. The following day, Mr Mulk Raj cancelled out in the examination hall what he thought was his best answer. But that did not prevent him from passing the exam creditably well.

After his BA degree, he joined the Law College, Lahore, on insistence of his elder brother. It was there that he came in close contact with the leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Lokmanya Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Pandit Moti Lal Nehru, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, Sardar Patel and many others. It was in Lahore again that in 1920 he got the job of a sub editor in Lala Lajpat Rai’s much acclaimed newspaper, the VANDE MATRAM. In time to come, he was to work also as a correspondent for the Free Press of India (later called United Press of India), the STATESMAN, the TRIBUNE and many other many national dailies as a correspondent.

ADMANTINE WILL

Mr Saraf returned to Jammu in 1920. He was 26, impecunious, unemployed and a married man at that. The dream to start a paper of his own and the will to accomplish it were all that he had. To sustain himself in the city, he served as an accountant in the private estate of Raja Hari Singh, who was later to ascend to the Dogra throne. On 24 June, 1924, he was able to come out with the first regular issue of the Urdu weekly, aptly named RANBIR – a knight in armour. But what a labour of love it was.

Trouble arose as the very idea of starting a newspaper in the feudal state gripped his mind. Why would he think of such a venture at all? He came under police surveillance but succeeded in allaying the unfounded suspicions. Then surfaced the problem of obtaining an official permission. The authorities rejected three of his applications. He made a fourth and the last attempt on 21 March, 1923. The Government machinery took over a year mulling over it before according him the permission on 28 March 1924. He was allowed to establish a printing press as well in the town.

Having crossed the Rubicon, Mr Saraf scrounged out his meagre savings and borrowed much more to meet the immediate expenses. A dilapidated structure was found to house the hand-driven printing press, a one-in-all handyman recruited to run errands and do sundry chores, professionals from the local government press were induced to do part-time work at the press, journalists and acclaimed writers from all over the State and British India were invited to contribute to the paper and advertisements booked for the prominent business houses. That all this was made possible in a short span of 88 days (28 Mar to 24 June, 1924) speaks volumes about the bone-breaking effort Mr Saraf and his manager Mr Vishwa Nath Wadhwa must have made to fulfil their cherished dream.

TRIALS AND TRIUMPHS

The RANBIR set off with a boom. Maharaja Pratap Singh fixed an annuity of Rs. 100 (later reduced to Rs. 50 by his successor, Maharaja Hari Singh) for the paper. The long list of subscribers read like a who’s who of the times.

Of the six objectives of the weekly, one was “to publish…interesting…happenings in the State…”(page 7, Fifty Years of Journalism). An issue carried the story of how ghee was being pilfered from the royal kitchen. Soon after, the Maharaja’s ADC was at Mr Saraf’s door to escort him to the Ruler’s private audience. Asked to divulge his source, Mr Saraf had the nerve to refuse the royal command. What followed left him amazed. The Maharaja asked Mr Saraf to take a seat near him “and then in a low and yet sublime voice told me (Mr Saraf) that he was never unaware of whatever was happening in his kitchen, but since I had given it publicity and voiced public feelings in the matter, he ordered his private secretary to honour me with an award of Rs 200.00 (equivalent to the cost of a robe of honour) as token of his appreciation (page 25, ibid).”

The RANBIR’s subsequent face offs with the likes of Mr BJ Glancey and Mr GEC Wakefield – two powerful Englishmen in the Dogra regime – were none so pleasant. Mr Wakefield, then working as the Chief Secretary to Maharaja Hari Singh, wanted Mr Saraf to write a piece on the lines dictated by him, which Mr Saraf refused to do. The canny bureaucrat apparently left the matter at that, silently watching for an opportunity to deal with the plucky journalist. Eventually, the permission to publish the RANBIR was withdrawn. But even the withdrawal indicated the high stature Mr Saraf had achieved. The order of 9 May, 1930, personally signed by Maharaja Hari Singh, said in part, “I desire to make it clear that it is not my intention to curb in any way the legitimate expression of opinion or fair and just criticism of the policy and acts of myself and my Government.” Ban or no ban, Mr Saraf, in collaboration with a couple of like-minded friends, started publishing another paper, named the AMAR (literally, the Deathless!) from Lahore.

The prohibition on the RANBIR was also lifted after a year and a half, on 13 November, 1931. The paper flourished on its revival. Three years later, the publishing house brought out a children’s magazine called the RATTAN, which was adjudged one of the three best edited periodicals for children in India. The popularity of the RANBIR increased with the passage of time, till it was virtually starved of funds and throttled to death in 1950 by the Government of Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah. As Mr Saraf put it, “It was indeed an irony of fate that the RANBIR….fell victim to a popular regime for whose establishment it had worked so hard…”(page 81, ibid).

By the end of the 1950s, the printing press, which had all along been a joint venture of the RANBIR, too had to be closed down in similar circumstances.

But did that end Mr Saraf’s commitment to his chosen profession? Not at all. He was never a passive witness to the upheavals that have made India – the state of Jammu and Kashmir in particular – what it is today. The State Government nominated him as Joint Secretary to the Central Committee to carry out publicity for the Jammu & Kashmir Bank which was established in 1931. While accepting the position, Mr Saraf chose to turn down the offer of monthly allowance of Rs 150/- that it carried, choosing instead to work for free. He, along with his eldest son Mr Om Saraf (who passed away recently), was in the forefront of the Roti Agitation in 1943, which woke up the State Government from its torpor to do something for the starving masses and he took up cudgels with the J&K Prime Ministers Sheikh Abdullah and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed for their arbitrariness and egotism.

A SOURCE OF INSPIRATION

Mr Saraf wrote his first article in the 1916 and more than seventy years on, he was still a working journalist, representing the HINDU; when after a brief illness, he passed away in Mumbai, on 21 February, 1989, at the age of 95 years. “With his long career in journalism, Shri Saraf is rightly regarded as the father of journalism in Jammu and Kashmir,” reads the citation of the Padma Bhushan awarded to him in 1976. Here was a man devoid of all the advantages of family support, professional expertise and the material wherewithal to fight it out in an oppressive milieu to achieve his objective. Yet, he came out with flying colours.

There is much talk of start-ups these days. If Mr Mulk Raj Saraf could do it in 1920s, why can’t our young men and women in J&K do it today? His life-story, FIFTY YEARS IN JOURNALISM, recently brought out in Dogri by his son, Ved Rahi, can be a source of inspiration for our young men and women.

Trending Now

E-Paper