K N Pandita

No astute statesman with a futuristic vision would have agreed to a ceasefire in Jammu and Kashmir in 1948 in circumstances in which India did. It was a political and not a military decision. The aggressor got recognition as a party to the dispute plus the legitimacy of a foothold in the strategically crucial area of the sub-continent.

The grapevine has it that when Indian troops were poised for an assault on Muzaffarabad – the gateway to the Northern Areas — after the recapture of Uri, a small hand-written note from Atlee was delivered to the Indian Prime Minister saying, “the understanding is thus far and no further.” Was Nehru a friend of the Soviet Union? Mind the cryptic remark about Nehru made by Stalin to Dr S Radhakrishnan, the first Indian Ambassador to Moscow: “He is the running dog of British imperialism.”

A few days before the declaration of ceasefire, a newsman asked Aristov, the correspondent of Tass in Srinagar whether he was confident that Indian troops would be occupying Muzaffarabad in a couple of days. He gave a stunning answer, “it will change the course of history of Asia if that happened.”

Only a few people know that Clement Atlee’s Labour government in Great Britain at the time of partition was desperate to see India agreeing to a ceasefire in J&K before her troops captured Muzaffarabad. The inference is that Nehru’s decision of ceasefire was emotional and not a cool-headed strategy.

The departing British colonial power was eager to retain influence in the strategic Northern Area through its Islamabad proxy. As the news of Nehru agreeing to a ceasefire reached Atlee, 10 Downing Street was agog with revelry and merriment. Fabian socialism had superseded the ideology of Marx and Lenin.

While India kept basking in Fabian socialism, China was wide awake and struck a deal with Pakistan handing ceding the Shaksgam strip of Hunza to Beijing which had already captured a large swath of land in Aksaichin on the north-eastern border of the original State of Jammu and Kashmir.

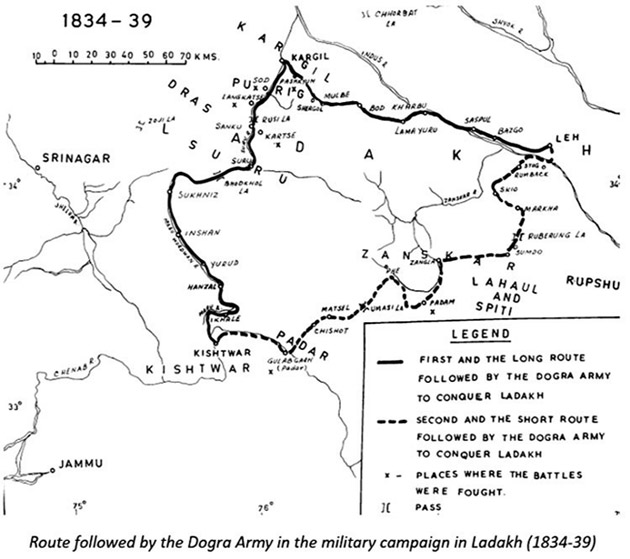

In the early 19th century, Maharaja Ranbir Singh, the second Dogra ruler of J&K had envisioned the security of his kingdom’s northern border. The brave and intrepid Dogra warriors under the command of celebrated General Zorawar Singh (1784 – 12 December 1841) made tremendous sacrifices and annexed the cold and mountainous Himalayan regions of Kargil, Gilgit, Baltistan, Ladakh and Tibet to secure the northern borders of Dogra kingdom.

In 1963, Pakistan, through an agreement ceded to China, nearly 5,200 km (2,000 sq. miles) north of the Karakoram watershed called Shaksgam. After the 1962 Sino-Indian border war, China retained about 14,700 square miles (38,000 square km) of territory in Aksai Chin and built a road across the region to reach Tibet. It will be noted that when Beijing marched troops to annex Tibet in 1950, Pakistan allowed US fighter aircraft to fly across its air space to support the resisting Tibetan troops.

For India and her security, the importance of Gilgit-Baltistan became obvious when China, already in tandem with Pakistan, floated the 47- 47-billion-dollar CPEC overland connectivity project.

China thus replaced the Russian ambition of reaching the shores of the Indian Ocean with accessing the Indian Ocean at the Gwadar port via the trans-Karakorum highway. China eyed the oil fields of the Gulf countries bypassing the crucial Malacca Strait where India and the US mounted guard against Chinese mischief.

Gilgit-Baltistan assumed strategic importance because of its link with Gwadar which also meant Sino-Pak intrusion into not only J&K but also the Middle East and Central Asia.

Reports are that the PLA has turned Gilgit-Baltistan into a strong Chinese missile base targeting India. China is reported to have dug caves and tunnels along the CPEC where nuclear devices are installed. China has taken over the development of crucial infrastructure in Gilgit and Baltistan including hydroelectric power generating projects and tactical airstrip. China has plans to move tanks and heavy armour along the Karakorum. Recently, a bid by jihadists to sneak into the Indian side somewhere in Machail revealed that China has dug a tunnel which the jihadists use.

Western powers’ curiosity, especially of the US, in Gilgit has not diminished. The US Congressional Research Service in its report of February 13, 2007, showed a map of the Indian subcontinent with Gilgit and Baltistan as a contiguous part of Pakistan and Aksai Chin as an “Indian claim.” India did not react.

Pakistan propagated that the ‘Northern Areas of Pakistan’ were not a part of Jammu and Kashmir in August 1947 and that India was in ‘illegal occupation of Siachen.’ But long back, the Azad Kashmir High Court had decreed that Gilgit-Baltistan are the part of former Dogra kingdom of J&K.

In May 2007, Baroness Emma Nicholson, the EU Rapporteur on Jammu and Kashmir refuted Pakistani claims citing historical evidence from maps of 1909 to Maharaja Hari Singh’s letter to Lord Mountbatten in October 1947 showing Gilgit and Baltistan as part of the State. Last year, a member of the American embassy in New Delhi paid a week-long visit to Gilgit – the Hunza region and interacted with local political and civilian figures. New Delhi raised the alarm that something messy was cooking on.

Trending Now

E-Paper