Charitanya Basotra

The great British writer, C.S. Lewis had this to say about the importance of literature:

“Literature adds to reality, it does not simply describe it. It enriches the necessary competencies that daily life requires and provides; and in this respect, it irrigates the deserts that our lives have already become.”

Now, the same holds true for a disillusioned Dogra’s life as well. A dogra goes out, perhaps to a national capital. Sees various people in a melting pot of various cultures and does not know to which part or place or shape or form or colour or language he belongs to. This alienness, which Marx called “disillusionment with the self” is perhaps the worst outcome of the consumerist boom of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Now, how do we do something about this? The simple answer would be, to resort back to what literature is, as Goethe, the national poet of Germany put it:

“A man should hear a little music, read a little poetry, and see a fine picture every day of his life, in order that worldly cares may not obliterate the sense of the beautiful which God has implanted in the human soul.”

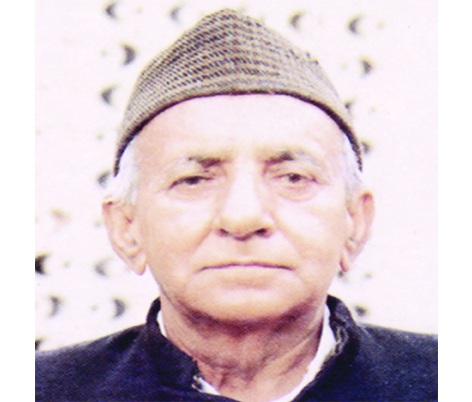

This is precisely why I decided to write this article. And I decided to write it on a man who is a giant in the literary tradition of the Dogras – Dinu Bhai Pant.

Birth and Career

Dinu Bhai Pant was born on the day of Baisakhi (11th May) 1917 in the village Painthal, to a family of humble means. This Village is situated near Katra in the foot hills of the Trikuta Hills. He completed a part of his education there and then went on to Reasi to get a degree . There at Reasi, his education was cut-short due to the untimely demise of his mother.

In 1937-38 he completed his higher education from Ranbir High School. In 1939 and 1941 he passed the “Bhushan” and “Prabhakar” Exams respectively.

In the beginning he composed witty and humorous poems. Not many knew at that time that in these satirical poems were present the seeds of an undeveloped genius. As the Voice of Dogras notes, he had inherited the satirical trait from the environment of wit and repartee prevalent in his village.

As his poetic prowess developed and fame reached even greater heights, he had the painful realisation that the number of educated people who would come to listen to the literary creations in Jammu did not exceed fifty or a hundred. And from then on, he started experimenting with the mother tongue of the masses – Dogri. As a result of this, Pant wrote his famous long poem ‘Shehr Pahlo Pahl Gaye’ in 1943. This was followed by ‘Chache Duni Chand Da Behah’.

In 1944 the Dogri language got a fillip with setting up of the Dogri Sanstha, a literary and cultural organization of which Pant was one of was founding members like Prof Ram Nath Shastri, D C Prashant, B P Sathe, N D Misra, Sansar Chand Baru and few others. The Sanstha while working for Dogri, also made endeavors for cultural rejuvenation. Earlier, in 1942, as a part and parcel of the nationwide Hindi rejuvenation movement, he had founded the Hindi Sahitya Mandal. He was also associated with Dogra Mandal.

Gutlun’s instant popularity set a chain reaction in Dogri poetry with a host of new poets writing in this language, bridging the cultural gap between the ruralite and the urbanite. Nawan Gran was the play, Pant wrote jointly with Prof Ram Nath Sahstri and R K Abrol. The tragic-drama, Sarpanch, written by him has frequently been played within and outside the State. Based as it is on folklore, it is the story of a village headman who makes supreme sacrifice for justice and honour.

Ayodhya in Dogri won him the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Award in 1985. In Ayodhya the author has adopted a very daring and unconventional way in dealing with the character of Kakae who was always depicted as villain in the Ramayana.

Throughout his life, he struggled ideologically and practically against tyranny and injustice. That is why in his popular poetry, he always supported the common man. In his play ‘Sarpanch’, Data Ranu who sacrifices his life in order to support the right cause, has been made the central character.

When a radio station at Jammu was setup in 1947, Pant worked for sometimes as a staff artist and later, as a casual script writer. In 1948, he was appointed the publicity officer in the Rehabilitation Department, which played a useful role in the rehabilitation of hundreds of thousands of refugees. He was made a Panchayat organiser in 1950. The state government promoted him to become an officer in the senior cadre of the state. He retired in 1978 as Deputy Provincial Rehabilitation Officer.

Dinu Bhai Pant died of a heart attack in 1992.

Legacy

Harbhans Singh notes that “In 1943, when Dinu Bhai Pant composed Sheher pehlo pehl under the genre of gitlu, the tickle or titillation, there was no forum for the poem to be published. The irrepressible poet would visit various neighborhoods of Jammu and recite his poem to all those who cared to listen. And, listen they did! It was that single poem that released the pent-up creativity of the Dogri-speaking people.

Those who study history of languages might be baffled by the fact that even though Dogri finds mention in Amir Khusro’s Masnawi Nuh Siphir, and subsequently, all through history there have been eminent people from the Jammu and Kangra region, who sporadically wrote in Dogri, yet it could never develop into a throbbing literary scene. Also, during the rule of Maharaja Ranbir Singh in the 19th century, it was the court language along with Persian. The literature, as we know it, came to be created only after the bold efforts of Dinu Bhai Pant.”

Works

Dinu Bhai Pant wrote countless poems, plays and essays. Some of them are:

– Guntlu

– Mangu dee Chhabeel

– Veer Gulab

– Dadi Te Maa

– Nama Graan

– Sarpanch

– Ayodhya

– Pratibha

Revolution and breaking away from convention and conservatism is something that lies embedded in Pant’s Poetry. In his poem, Guntlu, the verses he weaves like, “living in this slavery is worse than death” or “arise o farmer! wake up from your reverie o peasant”, direct the minds of the reader to revolt against the inequalities and exploitation of the common populace latent in the society of his times.

His verses in Guntlu that go like this, say the same thing:

Chohre Pehre Sihre par Kadke

kunda Saab salami Da

[your days and nights

Are spent in bowing down to your masters]

or

Jisne Kadein Buaal nee Khadya

dhrig dhrig us javani da

marne kola bhi manda loko

jeena iss gulaami da

[listen to me,

You are someone who has never

Tasted the vigour of youth

Worse than death

Is the life of enslavement

Which you lead]

These poems gained so much popularity, not just by the educated but the illiterate classes as well, that they were on everybody’s tongues. In his poems, ‘Sheher Pehlo pehl gaye’ and ‘Chacha Dhuni Chand da Vyah’ he put forth the disillusionment that a village lad faces upon going to the cities as well as the illiteracy prevalent in his times. The poem ‘Lund Leader’ epitomises the poetic fervour latent in Pant’s poems of this time:

Mandir Masjid kadein jammiye nee dikhee jinne

sandhya namaj ik akkhar nee sikkhee jinne

Majhabi katabei da nee, na tak nee baakha jinne

unne chuttein – chuuchde dee pai dee dhamaldharee

[those who have neither seen mosque or temple,

Those who know niether the a of the evening prayer

Nor the z of the dawn’s call,

Those who know not even the names

Of religious scriptures,

They are the ones who rule the roost].

In pant’s poetry, one finds a fervent aggression directed against the forces of feudalism prevalent in the Dogra society of that time. For example, in one of his poems he says:

lok meehne maarde dogrein daa raj ae

dogrein daa haal manda jurda nee saag ae.

[taunts abound that the dogras rule us all

But look at the irony in a poor dogras life

A life that doesn’t even beget two square meals

A day.]

In his poem ‘Veer Gulab’, Pant talks about the bravery, gallantry and valour that characterises the common Dogra’s psyche. He does this through beautiful, imaginative metaphors and personifications, bringing out Gulab Singh from the after-world right in front of the eyes of the reader. He writes thus:

Dogrein te ghode dorde jandde

bariyan de tht trorde jande.

Veer gulab dee vakhree toli

pralay de doot kherde holi.

[the horses of the Dogras keep on marching,

Enemies they go on destroying.

Gulab the Gallant’s men are different

When they go marching

The angels

Start playing with the colours

Of doom.]

In his 4th major work, ‘Dadi te Maa’, Pant masterfully expresses a simplistic narrative by weaving it into the contours of a simple language, which the common folk speak. It is a poem about the common folk, in a language of the common folk, by someone of the common folk. The same etchings are found embedded in another poem – ‘Kehdee Basant te Kohdi Basant’.

Kehdee Basant te kohdee basant

dukkhe da anntt na bukhe da anntt

[which spring and whose spring,

Neither is there an end to hunger

Nor does there seem an end to this

sorrow.]

In Pant’s poetry lies seeds of a revolution. A social revolution. A revolution against stasis and a revolution towards dynamism, towards change, towards growth. He is perhaps the greatest Dogri poet because he talks about the problems which the people faced. In that sense, Dinu Bhai Pant is the poeple’s poet. In that sense, Dinu Bhai Pant, is perhaps, the greatest Dogri poet there has ever been.

Trending Now

E-Paper