Prof D Mukhopadhyay

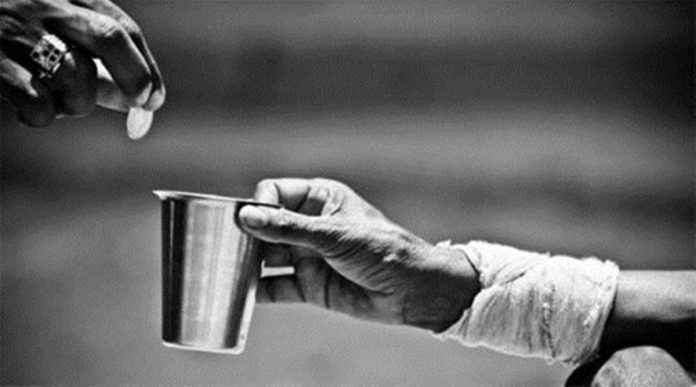

India, a land of diverse cultures, rich history, and vibrant traditions, often finds herself in the state of being humiliated and bewildered when she is portrayed negatively showing beggars fighting for coins, gathering for leftover food, and vulnerable individuals, including women and children, in distressing conditions. This situation reflects poorly on India as a country of beggars, snakes’ charmers, and superstitions by media, different forums and many quarters while these projections are sometimes hurtful and humiliating, they do not accurately represent the true essence of India although the picture is partly factual and true. India has been endeavouring constantly to address all kinds of socio economic evils including beggary a stop priorities but due to certain inherent shortcomings, she could not achieve success in entirety so far. Begging is mostly a socioeconomic problem. Many are of the views that begging has been turned into a profession and street begging not only harms the economy and the environment but also challenges social cohesion. Moreover, citizens also are urged not to give alms to beggars but to support the government in eradicating this issue.

While beggars may hinder economic progress, they do not pose a direct threat to society. It is imperative to mention that none prefers begging and begging seems to be the hope for living as the source of the minimum sustenance level. It is a dire need for India to make herself free from this serious socioeconomic evil of beggary which to some extent makes the country tagged with beggary and it is indeed very disgraceful to every Indian. This is factual that India has achieved considerable extent of socioeconomic and technological development and beggary is certainly a matter of embarrassment for India aspiring to be a developed nation in next two decades.

Of late Government of India adopted the ‘Bhikshamukt Bharat Plan’ which identified 30 cities to be made free from begging by 2026. In this context, it is worth mentioning that begging was also identified to be a serious issue earlier during the ‘Emergency’ and the later initiative of Delhi Government to provide a three month- skill-training program for beggars but neither was successful in achieving the target. In recent past, the Honourable Supreme Court of India refused to accept PIL against beggary and beggars’ rights and contrarily, recognised beggary as a socioeconomic problem fuelled by poverty, lack of education and employment opportunities and the state is duty bound to protect the rights of the citizens to life and live with dignity. It may be mentioned that Article21 provides Indian citizens the right to life, the right to live with human dignity including livelihood. Further, the Constitution guarantees through Article 23 that the right to life is free from exploitation. Article 23 was integrated to stop beggary and other forms of human trafficking. Article 23 read with Article 39 (e) and (f) of the Constitution furnishes for the Directive Principles of State Policy and grants the state to protect persons from exploitation.

The meaning of the word “Begging” as per Section 2(i) of the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959(hereinafter the BPBA, 1959), requesting or receiving alms, in a public place whether or not under any affectation such as singing, dancing, fortune-telling, performing or offering any article for sale; entering on any private premises to request or receive alms; uncovering or displaying with the object of acquiring or extorting alms, any sore, injury, distortion of diseases whether of a person or animal; having no visible means of resource and meandering, about or remaining in any public place in such condition or manner, as makes it likely that the person doing so exist requesting or receiving alms; permitting oneself to be used as a display to request or receive alms but does not include requesting or receiving money or food or given for a purpose approved by any law, or sanctioned in the way prescribed by the Deputy Commissioner or such other officer as being determined for this sake by the Chief Commissioner. All offences under this anti-begging law were recognized and necessary laws were enacted and brought into force by almost all the State Governments and Union Territories in India and the said laws summarily provide that if any individual utilizes or makes any other person request or receive alms, or whoever having the guardianship or charge of the child, schemes or empowers, their work or the making the child request or receive alms or uses someone else as a display, shall be punished for imprisonment for a term up to three years but which shall not be less than one year.

Under the given scenario, it may not be an exaggeration to suggest that begging is more of a socioeconomic issue than a law and order problem, requiring an economic solution rather than strict legal enforcement. The Supreme Court’s refusal of a PIL against beggary in 2021 and the Delhi High Court’s decision in the landmark case of Ram Lakhan v. State are heartening and welcome. The Delhi High Court departed from the conventional legal approach of criticizing begging and instead focused on a comparative analysis of the legal doctrines of necessity and pressure, as well as the constitutional principles of equality and liberty. The court addressed begging in the context of Articles 19(1)(a) and 21 of the Constitution, ruling that unreasonable restrictions on begging are unconstitutional as they perpetually deprive beggars of fundamental rights.

Specifically, the Delhi High Court, on August 8, 2018, decriminalized begging by striking down relevant provisions of the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959, as extended to Delhi. The judgment, which stemmed from two PILs challenging the constitutionality of the Act, upheld Section 11 while striking down all other provisions that criminalized begging. This ruling underscored the need for a shift in government policy from punitive measures to rehabilitative ones, achieved through amending or enacting laws and integrating beggars into society through empathy and compassion. Prior attempts to eradicate begging failed due to the lack of robust rehabilitation plans. Current anti-begging laws are flawed as they criminalize beggars without addressing the root causes. It is essential to educate the public and implement comprehensive solutions to eliminate begging and prevent its recurrence.

Tackling the problem of beggary in India requires a comprehensive strategy. One crucial aspect of addressing this issue involves establishing robust social welfare systems to assist those in need. This includes ensuring access to education, healthcare, and employment for marginalized groups. Additionally, it is essential to enforce laws against forced begging and the exploitation of beggars more rigorously. Authorities need to dismantle organized begging networks that exploit vulnerable individuals for profit, through targeted law enforcement and collaboration between government bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).Changing societal perceptions of beggars is also crucial. Rather than stigmatizing them, efforts should focus on integrating them into society and providing the necessary support for them to live with dignity. This can be achieved through educational campaigns that challenge stereotypes and promote empathy towards beggars. India’s Constitution provides a solid framework for addressing poverty and social welfare issues. Article 41 mandates the state to provide public assistance to those in need and prevent the concentration of wealth to the detriment of the common good. While the country’s legal system, such as the BPBA, 1959, criminalizes begging and allows for the detention of beggars, there are concerns about the effectiveness of such laws in addressing the root causes of beggary. A more holistic, rights-based approach is needed. Although the issue of beggary in India is complex, it is not insurmountable.

Implementing a multifaceted approach involving social welfare, enforcing anti-begging laws, and changing societal attitudes can help India address beggary. Providing education, healthcare, and employment can lift marginalized communities out of poverty. Strict laws against forced begging protect vulnerable individuals, while dismantling organized begging networks disrupts exploitation. Changing attitudes through education fosters inclusion. Upholding constitutional principles and a rights-based approach ensures sustainability. By addressing root causes, providing welfare, and changing attitudes, India can eliminate beggary, allowing all citizens to lead dignified lives. This effort, akin to past public health successes, can propel India toward developed nation status by 2047.

(The author is an Educationist and Management Scientist)