WASHINGTON: Scientists have discovered a new bacterial protein that could help detect and collect the rare-earth metals from the environment used in making smartphones.

The protein is 100 million times better at binding to lanthanides or the rare-earth metals than to other metals like calcium, said researchers from Pennsylvania State University(Penn State) in the US.

Two studies, which appears in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and the journal Biochemistry, describe the unique structure of the protein, which likely plays a role in its remarkable selectivity for lanthanides.

“Recently, there has been a lot of interest in increasing accessibility of rare-earth elements like lanthanides, which are used in the screens and electronics of smartphones, batteries of hybrid cars, lasers, and other technologies,” said Joseph Cotruvo, an assistant professor at Penn State.

“Because the physical properties of rare-earth elements are so similar, it can be difficult to target and collect one in particular,” Cotruvo said.

“Understanding how this protein binds lanthanides with such incredibly high selectivity could reveal ways to detect and target these important metals,” he said.

The team discovered the protein, which they named lanmodulin, within the bacterium Methylobacterium extorquens, which grows on plant leaves and in soil and plays an important role in how carbon moves through the environment.

The bacteria require lanthanides for the proper function of some of their enzymes, including one that helps the bacteria to process carbon, which is required for its growth.

“These bacteria need lanthanides and other metals like calcium to grow,” said Cotruvo.

“It appears that these bacteria have developed a unique way to target lanthanides in the environment, where they are much less abundant than other metals like calcium,” he said.

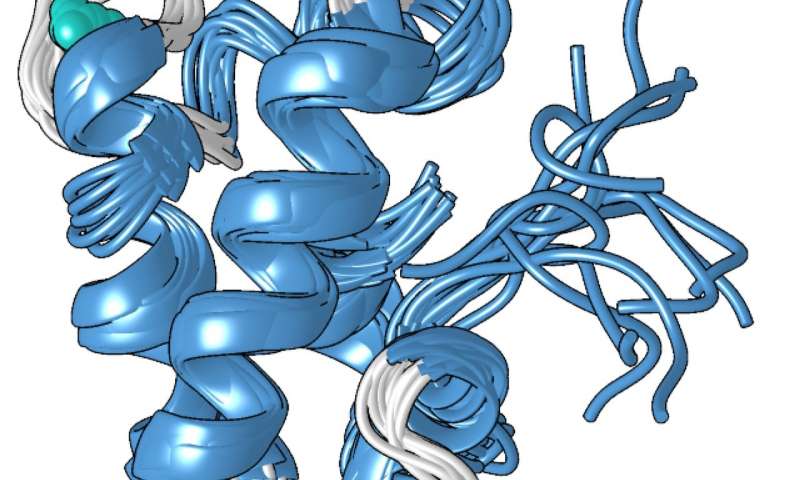

The protein’s unique structure, which Cotruvo determined in collaboration with the lab of Scott Showalter, an associate professor at Penn State, may explain why it is 100 million times better at binding lanthanides over calcium.

In the absence of metal, Cotruvo said, the protein is mostly unstructured, but when metal is present, it changes conformation into a compact, well-defined structure.

The new compact form contains four structures called “EF hands.”

Human cells contain many proteins with EF hands, which are involved in using calcium for functions like neurons firing and muscles contracting.

These proteins also bind lanthanides, though lanthanides are not physiologically relevant in humans and the proteins are only 10 or 100 times more likely to bind lanthanides than they are to bind calcium.

The compact structure of the lanmodulin protein also contains an amino acid called proline in a unique position in each of the EF hands, which may contribute to the protein’s lanthanide selectivity.

“The mechanism of lanmodulin’s selectivity for lanthanides is not yet clear, but we think it comes down to the structural change that occurs in the presence of metals,” said Cotruvo.

Understanding how the protein is so selective may provide insights for the collection of lanthanides for industrial purposes, including extraction from mining waste streams. (AGENCIES)

Trending Now

E-Paper