Ashok Ogra

Bansi Parimu: Kashmiri by birth, secular by natural bent, social activist by calling, conversationalist by natural instinct, communist by belief and an artist by choice. And what an artist!

For Bansi, Kashmir represented a collection of lines, shadows and contours. When he painted, it always had a deep cultural shade or story to convey.

M F Husain had this to say when seeing his work:’The colour, the sound of its landscape create an orchestra of nature’s bounty. Parimu’s paintings keep singing the song of creation that is Kashmir on our planet.’

While the earlier painters of Kashmir, S.N.Butt and D.N.Wali, opted for ‘on the spot’ treatment for brilliant descriptive scenes, Bansi would create the atmosphere of landscape in an abstract language, distributing a rich colour across a surface- instead of the canvas as a decoration.

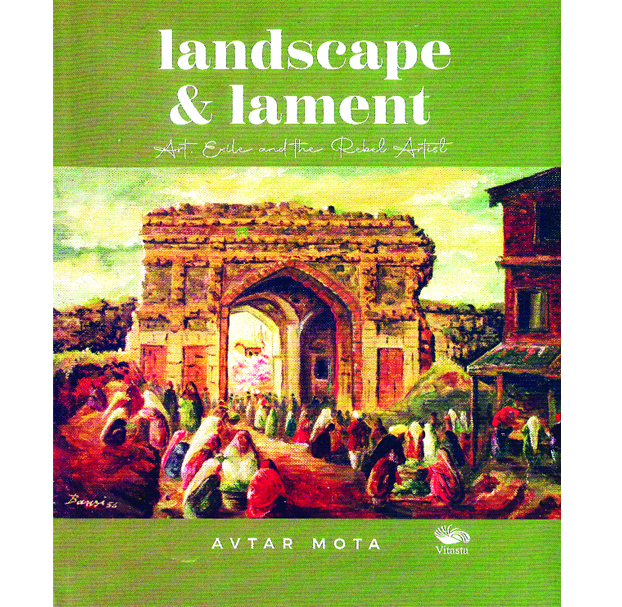

His entire journey as an artist is best captured in the just published book KASHMIR LANDSCAPE AND LAMENT: ART, EXILE AND BANSI PARIMU, THE REBEL ARTIST by photographer, poet and writer Avtar Mota.

This voluminous book has many elements jostling for our attention: the history of art in Kashmir from ancient times to the Mughals, the post-independent art movement and Bansi Parimu’s journey as an artist. Through Mota’s painstaking research, we learn of the ideas and inspirations that influenced Bansi and get a glimpse into one of the great creative minds of Kashmir and, indeed, India.

In his preface, the author writes of the non-conformist nature of Bansi Parimu: “he learned the art by total observation and self-education by putting into practice the philosophy of neither this nor that, i.e. the significance of the view is in the eye of the beholder.”

Kashmir had abundance of nature’s wealth to inspire Bansi. His work had none of the damp, green, memory-sudden melancholy of a typical valley of the west. His was gorgeous, vibrant colours.

In the words of noted art critic Keshav Malik ‘his work is a ‘mathematical token of the soft fall of the Shikara oars- its slow progress emphasizing the quality of sacredness one associates with things of the risen spirit.’

He defied conventions- and experimented with different styles and mediums. According to noted broadcaster and poet Shantiveer Kaul who knew the artist rather intimately, Bansi started from landscapes, experimented with cubism, moved to figurative style and finally settled at pure abstracts.

He watched people go about their daily routine and apprehend the rhythms of their lives. KATHI DARWAZA captures the essence of early morning in subdued colours with splash of white deployed to distinguish each character, and TAHAR (Yellow Rice) done in emerald green – both reflect the artist’s fascination to bring out active life- spirit of the ordinary Kashmiris.

The torment of losing his mother when just 10 years old found expression in WAILING WOMEN and THE GRIEF WITHIN.

His younger daughter J.P.Chandrika provides an interesting insight into when Bansi would engage in painting: ‘he locked himself in his studio for days to paint relentlessly. And the outcome of the days of hard work would be a breathtaking piece of art with the most vibrant and lively colours.’

Mota is at his best when explaining the artist’s abstract work : ”his abstracts are not merely markings, organic shapes, smudges, smatterings, conical ovals, rings, bright colours, blots, drippings, sprays and squeezes but skillful use of lines, shapes, colours, and pattern to create rhythm on canvas.”

Bansi had a remarkably steady and unfailing hand and mind.

His nephew Vijay Vishen recalls ‘once I showed him a few pebbles picked up by me from Lidder stream in Pahalgam in Kashmir. He took a large and irregular piece from the collection and in a few minutes transformed it into a beautiful paper-weight with a symbolic ‘foot and flower’ painted on it.’

India Coffee House, Srinagar was an intellectual and social hub. Capt. S.K.Tikoo recounts an interesting encounter with M.F.Hussain: “Hussain disliked the noise and cigarette smoke inside the Coffee House. He would pull me out of a gathering and say: come captain, let us go to the balcony. Let us wait for Bansi there.”

Bansi was also politically very active. He founded the Democratic National Conference – aimed at bringing together like-minded leaders on a common platform for a common cause. He enjoyed interacting with leading personalities of the state – G.M. Sadiq ,Shamim Ahmed Shamim, D P Dhar etc…Incidentally, Bansi had also painted portraits of a few well known personalities including the UAE royal family and Karl Marx.

It is worth mentioning that artists like Tyeb Mehta, M F Hussain and a few more would urge Bansi to migrate to a bigger city to gain great recognition. But Bansi was wedded to the soil of Kashmir and the colours of the valley served as his inspiration. He was at his peak – participating in several prestigious exhibitions both in India and abroad and being conferred with several awards- when the political developments took an ugly turn in the mid 1980s.

This exchange with the then Home Minister S.B.Chavan provides us with an inkling of the author’s foreboding of the things to come. The minister was visiting the valley in 1986 in connection with the ‘Hangul Conservation Project ( Bansi was deeply involved in the Hangul conservation project and save the Dal). During an interaction with the civil society, Bansi got up and said: I believe you are interested in the preservation of the endangered species of Kashmir stag or Hangul… but why can’t you do something about the other endangered species here- Kashmiri Pandits.

After the unfortunate exodus of Pandits from the valley in 1990, it was the pain of ‘homelessness’ that deeply disturbed him, addressing the conflict as a subject in his art.

Figurative abstracts COBWEBS OF APATHY, SMEARED SNOWS, RED KNOWS NO CREED… all evoke delicate layers of emotions of migration, rife with pain and anguish but no trace of revenge.

Noted poet AgniShekhar refers to an encounter Bansi Parimu had with a journalist: ‘why did you refuse to accept the migrant’s allowance?’ Bansi replied,’it is so humiliating. Anyone with self-respect will not seek it.’

Prof. Jaya Parimu poignantly recalls the last few days before the death of her husband: ‘on July 27,1991, my daughter Jheelaf suddenly telephoned me and said, ‘daddy has a gangrene wound and he needs immediate hospitalization’. And we rushed to Delhi. He was admitted to AIIMS on July 28 and on July 29 he was no more. It was so sudden that I had no time to sit and grieve. With his death, many dreams and plans he had nourished fell to the ground.’

Described as ‘God’s gift to Kashmir’ by noted broadcaster & poet Farooq Nazki, Bansi had infinite charm and unsurpassable dignity. Tragically, he died with a deep scar in his heart.

In fact, the agony of leaving one’s homeland affected many Pandit artists, including Triloke Kaul, Mohan Raina and P.N.Kachru.

The book stands out for incorporating the views of all those who knew him and were familiar with his work : Padma Shri K.N.Pandita, M. S.Malik,Sardar Santokh Singh, Makhan Lal Saraf, Kashmiri Khosa, Hriday Kaul Bharti, Arvind Gigoo, H. N.Jattu, M.K.Tikoo, Bihari Kak, Sudesh Raina, Abdul Majid Baba , Santosh Tiku, T.K.Walli, Indu Bhushan Zutshi, Ramesh Kumar Bhat, Kapil Kaul, Bashir Budgami,Nighat Hafiz and Peter Raina – in addition to those mentioned in this feature.

Published by reputed Vitasta Publications, this book is a work of art, brilliantly illustrated with samples of the artist’s work and family photos. Thanks to the author, we also get to know about the many other hobbies that Bansi engaged in: photography and playing flute, an interest in architecture and poetry. Padma Shri Pran Kishore reveals that Bansi also worked as a photographer and correspondent for the English weekly CRITERION.

There is something very warm and very chilling about his work. The warmth comes from the artist’s profound love of the times past. The chill comes from experiencing migration and rootlessness,- silently lamenting ”where I have come from is disappearing, I am unwelcome and my beauty is not beauty here.”

He nursed the hope of returning to his dear Kashmir, recalls M.K.Raina, noted theatre director.

His elder daughter Jheelaf Parimu best describes her father as someone who was born ahead of his time. ‘I feel Kashmir was not ready for him; even India was not ready for him…Despite all his achievements, he died unsung.’ Similar sentiments are echoed by noted artist Veer Munshi: ‘Bansi had the potential to be a Hussain but he did not survive.’ Bansi was in love with life but too shy to promote his work – though lately his work seems to be gaining greater appreciation, and as per Jaya Ji the painting SMOLDERING CROCUS got sold at a decent price. Today, his work decorates many galleries and collectors within the country and outside – thus immortalizing his memory. Bansi was like a hurricane- a colourful one, leaving behind a multifaceted legacy!

(The author works for Apeejay Education Society, New Delhi)

Trending Now

E-Paper