Lalit Gupta

Recent chance discovery of ancient coins of Sultanate period datable to circa 12th century CE, from Jammu’s Kot Bhalwal Jail premises, has generated lot of interest amongst general public as well as scholars and historians.

While for public it is like a virtual consummation of primeval human pre-occupation with fairly tale run into with hidden treasures, unexpected gains, for the writers of history the latest discovery of coins has come as an opportunity to re-assess the influence of Delhi Sultanate on Jammu region, as revealed in number of old textual sources.

For penning down the past of a place and its people, the coins, along with conventional sources like manuscripts, epigraphs, visual arts et al, have also proved to be a reliable material basis for reconstruction of administrative and other alternate histories of the issuing dynasty. The study of coins called Numismatics, in fact has been used for historiography in India as far back as 11th century by Kalhana, the author of Rajatarangini.

The script and system of weights was well established during Harappan culture, which incidentally also marks the first urbanization in Indian sub-continent. According to modern scholars the coined money was current from the Vedic period that extended from circa 2500 to 800 BCE. But it is with earliest punch mark coins, that the origin of coinage is firmly associated with second urbanization that took place in Gangetic valley from 800 BCE onwards. Literary sources such as Panini’s Ashtadhayi, Buddhist cannons like Vinay Pitika, Jataka stories and Kautilya’s Arthashashtra refer to coins with names like kahapana, ardha kahapanna, pada, mashaka, kaakani et al.

Ancient coins are discovered on surface, in excavations and in hoards. The evidence of coins is partly internal like physical body of the coin; kinds and proportions of metals or the fabric used, weight, distinct types and their continuation, symbols, monograms, legend— inscriptions with names of cities, corporations etc. While the partly external evidence speaks of outside association of the coin such as geographical distribution, quantity as related to quality, over-striking: when a ruler strikes his emblem or symbol over coins already issued by a previous authority.

For instance the purity of the coins also reveals the economic conditions of a period, their discovery away from the place of their origin can give an idea bout about the extant of circulation which in turn can throw light on political and economical influence of issuing dynasty, authority.

Earliest coins of India are Punch Mark Coins, which started in the 7th or 6th century BCE. These get their name because of the making technique in which coins are marked with stamps of various symbols. These coins were issued during Janapadas and Mauryan period. No such coins have been reported from Jammu while from excavations at Semthan in Kashmir, the punch mark coins in copper and rarely in silver have been found.

Silver punch mark coins were often made up of cut-up sheets of silver, and were stamped with five small symbols. Square copper coins were also made with the similar symbolic designs. Thereafter, the Indian tradition adopted the foreign coinage tradition. It was a fusion of traditions. The earliest coins contain a few symbols, but the later coins mention the names of kings and gods or dates.

Jammu region, referred to as Darva Abhisara in Puranas, has been a part of the Madra Mahajanapada from 600 BCE onwards. Sandwiched between the Vale of Kashmir to the north and the Punjab plains to the south, the Shivaliks comprise most of the region of Jammu. Pir Panjal Range, the Trikuta Hills and the low-lying Tawi River basin add diversity to the terrain of Jammu. Prior to the 14th century Jammu and Kashmir were ruled by a series of Buddhist and Hindu dynasties. As Islam tightened its hold on the northwest of India, a succession of Muslim sultans occupied Kashmir until Akbar’s annexation in 1587, after which it became the summer resort of emperors of Delhi. Billawar was the capital till 1630. The rule of Rajput dynasties of Duggar along with few Muslim rajas, continued during 17th & 18th centuries. Ranjit Dev was the most successful of such rulers who unified 22 hill principalities into one Jammu kingdom that enjoyed exceptional prosperity during mid 18th century because of Raja’s political acumen.

Nothing is known about the exchange system of those tribes that lived in Jammu thousands years ago. However it is possible that like other parts of sub-continent the barter system was popular here on those days. The nomadic tribal groups in remote areas of the State are still following this old practice.

So far as the question of introducing coins in Jammu is concerned unfortunately no numismatic findings have been systematically recorded and studied. The official collections of coins found in different parts of Jammu and Kashmir during past years is lying with with Archaeological Survey of India, Dogra Art Museum, Jammu and SPS Museum, Srinagar and also in various museums of the country and abroad like British Museum and Victoria Albert Museum, London etc.

European Archaeologists were first to introduce the numismatic Study in India. They studied the ancient Roman and Greek Coins found in various Indian states. The initial Jammu & Kashmir coinages were also deciphered by these experts like Alexander Cunningham, who published a paper in 1843. C J Rodgers British numismatist published his research paper on copper coins of the Sultanate period in 1885. G.B. Bleazby, was another coin expert who worked as the first Accountant General of Jammu & Kashmir during the period of Maharaja Pratap Singh. He in year 1900 prepared the first list of about 1500 coins preserved in the S.P.S. Museum at Srinagar. Subsequently in 1923 Ram Chandra Kak in his Handbook of the SPS Museum gave brief Account of the numismatic section of the museum.

The detail studies of Kashmiri coins by Indian and foreign scholars, have cleared many misgivings about the chronology of Kashmiri Kings, economic conditions and cultural relations with neighboring areas. But unfortunately so far no such exclusive authoritative study Jammu coins has been undertaken.

Other than stray mention in reports of Archaeological Survey of India, the only significant research on Jammu coins was initiated by Prof SS Charak, the prolific historian and writer of monumental ten-volume history of Himalayan States. Unfortunately due to his untimely demise the work started by him and based on the valuable collection of Jatinder Mahajan from Pathankot and other sources remains incomplete till date.

It is in this context the excavations carried out by Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) at Ambaran, Akhnoor, in 1999-2000, under supervision of Dr B R Mani, presently Joint Director General of ASI, New Delhi, are significant as along with architectural remains of a grand monastic complex and number of antiquities, eight Kushana coins were also unearthed. These circular copper coins belong to Kushanas rulers like Soter Megas, Kanishka (c.127-151 CE) and Huvishka and one perhaps to Toramana, the Huna ruler.

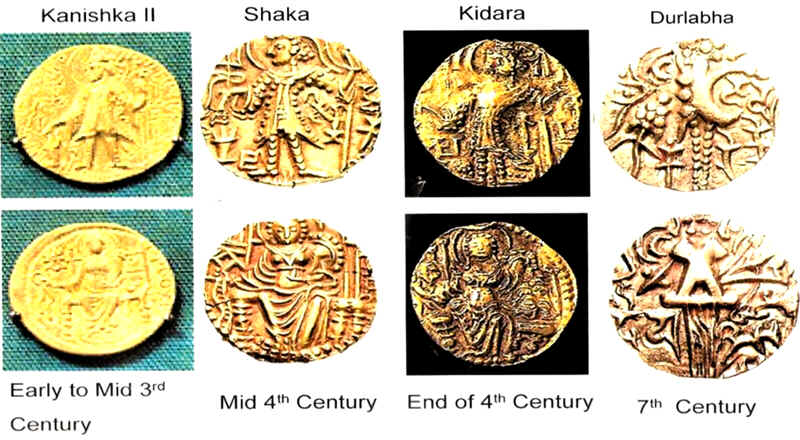

Kushana period seems tom have been of great socio-cultural development in both Jammu and Kashmir. Dozens of Kushana sites yielding antiquities and coins have been found in Jammu including Kirmachi. In 1970’s the conservation of the Kirmachi temples revealed that the temples were built on earlier brick foundations dateable to the Kushana times. Thus the coins found from that site pointed to a vibrant phase of Kushana and Kidara Kushana rule in Jammu region from later decades of 1st century BCE to 5th century CE when Huna’s invasion had devastated north India.

Other significant finds in Jammu region has been that of coins with Sharda script. Some of these were reported from Babbor, which boasts of 11th-12th century group of medieval temples. Coming from a site that is considered as the ancient capital of Duggar, the coins found from the temple complex, not only substantiate the references in 11th century Rajatarangini, of rulers of Jammu principalities having a close relation with Kashmiri kings but also that in Jammu region like contiguous areas of Himachal Pradesh the script in vogue was Sharda out of which the later day Takari script had evolved.

Rise of Muslim Sultanate in Delhi and its subsequent strong hold on north India saw Jammu coming under the subjugation of Delhi rulers. The copper coins found from Kot Bhalwal Jail like many other such finds not only testify the dominant currency of the times but also that the coins of copper speak mainly of internal circulation of the currency.

The excavations carried out by ASI at Guru Baba Ka Tibba, near Marh in 1997-98, had revealed few coins belonging to Zaiun-ul –Abidin popularly called as Bud Shah, who ruled Kashmir from 1420 to 1470. It can be thus safely assumed that the prosperity of Kashmir during Bud Shah’s time may have led to trade relations of Jammu with the Valley.

From late 16th century onwards both Jammu and Kashmir were incorporated into the Mughal Empire. The Moughal coins were the major currency in the region. After the power of Delhi rulers waned in 18th century, Jammu’s Raja Ranjit Dev’s son Brij Raj Dev struck coins in the name of his father.

According to numismatic experts the reignal year (RH) used on these Jammu coins is related to Mughal emperor: Shah Alam II, who ruled from AH 1173 to 1221 (1753 to 1806 CE). These coins have been minted using his reignal year from 1779 to 1783 CE and also as VS 1841 RY27 and RY28 (1784 CE). Evidently new obverse dies were produced regularly because of the need to change AH dates or mintmarks, but old reverse dies with obsolete reignal year were used until worn out.

The Sikh coins mark the next stage of popular coinage in the region. Sikh Empire of Punjab covered a huge area in the North-West of India. The monetary system of Sikhs consisted of coins and tokens in metals of Gold, Silver and Copper. The coins were produced in denominations of Mohur, Rupee and Paisa. Sikh currency popularly called as Nanak Shahi, other than Amritsar, was also minted in the cities of Lahore, Multan and Peshawar. The sovereign Sikh rule by Maharaja Ranjit Singh began in 1801AD, the Sikhs had established control over Lahore in 1765AD itself and had started minting and circulating their own coins. The Sikh coins were circulated over a large territory for more than eighty years and have also been reported from J&K that it remained a Sikh territory till 1846.

Gulab Singh, who became Maharaja of the composite state of Jammu and Kashmir in 1846, continued the Nanakshahi coins but added Zarb-e-Jammu. Maharaja Ranbir Singh, his successor also continued with the old practice. It was in the times of Maharaja Pratap Singh that the English currency like other British practices was slowly adapted in day to day life in Jammu & Kashmir. Thus ending the ingenious system of coinage in the region.

Trending Now

E-Paper