Prof Suresh Chander

suresh.chander@gmail.com

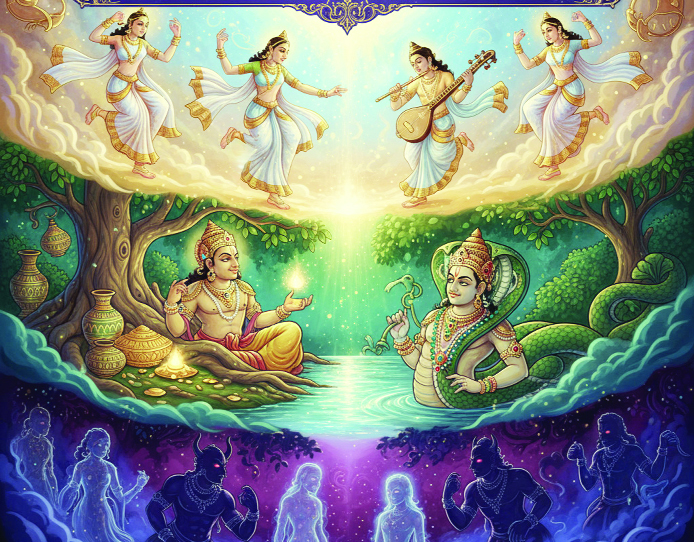

Hindu mythology stands out among the world’s major religious traditions for its extraordinary plurality of divine and semi-divine beings-devas, daityas, asuras, yak?as, n?gas, apsar?s-and a uniquely powerful and autonomous group of female divinities. While many ancient cultures once possessed similarly complex pantheons, few have survived into the modern era with the depth, continuity, and cultural vitality seen in South Asia. This article examines the historical, cultural, and philosophical reasons for this diversity and explains why Hindu traditions retain both male and female divine figures, including the Nine Goddesses of Navratri, in a manner unparalleled in most other religions.

A Civilizational Tradition Rather Than a Founder Religion

Hinduism is frequently described by scholars as a civilization rather than a doctrinal religion (Thapar 2009; Michaels 2004). Unlike Christianity, Islam, or Buddhism, which trace their origins to distinct teachers and decisive revelatory moments, Hinduism emerged from a long continuum of cultural evolution.

This absence of a single founder or central authority meant that:

* Vedic deities (Indra, Agni, Varuna),

* pre-Vedic mother-goddess cults,

* regional and tribal deities,

* tantric traditions, and

* philosophical abstractions like Dharma and K?la were absorbed rather than displaced (Witzel 1995; Flood 1996).

The result was an “accumulative” religious landscape in which myths from different eras and cultures coexisted instead of being harmonised into a single doctrinal vision. This syncretic capacity became a defining feature of Indian religiosity.

Pluralistic Cosmology Versus Monotheistic Compression

Abrahamic religions operate largely within a dualistic cosmology: God versus Satan, divine will versus evil (Armstrong 1993). The goal of religious structure in these traditions is the streamlining of supernatural entities under a single omnipotent deity.

Hindu cosmology, by contrast, is pluralistic and graded. The Vedas divide cosmic beings into:

Devas, associated with order, luminosity, and harmony, and Asuras/Daityas, associated with elemental power, ambition, and disruption.

Crucially, both groups originate from the same sage, Kashyapa, through his wives Aditi and Diti, as described in multiple Puranic genealogies (O’Flaherty 1975; Wilson 1840). The implication is philosophical rather than mythic: opposing forces arise from a shared cosmic source.

Thus, daityas are not “devils” but morally complex beings essential to cosmic balance. Figures such as Prahlada or Bali underscore this nuance. This worldview differs fundamentally from monotheistic traditions where the opposition between good and evil centres around a single adversarial figure.

The Independent Goddess: A Uniquely Indian Contribution

Perhaps the most striking feature of Hindu mythology is the centrality and autonomy of the Goddess (Devi). While other ancient civilizations worshipped powerful goddesses-Greek Athena, Egyptian Isis, Mesopotamian Inanna-these traditions faded with the rise of monotheism (Lévi-Strauss 1978; Leeming 2010).

In India, however, goddess traditions not only survived but expanded into a diversified theological system:

Vedic goddesses such as Ushas and Sarasvati;

Puranic goddesses such as Durga, Lakshmi, Parvati;

Tantric forms such as Kali and Tripura Sundari; and

thousands of village and regional goddesses.

The Devi Mahatmya (c. 6th century CE) is seminal in this evolution, presenting the Goddess as the supreme cosmic principle-self-existent, uncreated, and the source of all divine power (Coburn 1991; Brown 1990). The famous theological dictum encapsulates this worldview:

“Without Shakti, Shiva is shava (a corpse).”

Such theological elevation of the feminine has no parallel in Abrahamic traditions, where revered female figures do not attain divinity.

Integration of Indigenous Traditions

Archaeological and anthropological works show that prehistoric and protohistoric India possessed strong mother-goddess and fertility cults (Marshall 1931; Chakrabarti 1999). As Indo-Aryan culture spread, these indigenous traditions were not suppressed; they were gradually woven into the Sanskritic framework (Fuller 2004; Krishnan 2017).

Thus, Hindu mythology today contains elements from:

pastoral nomads,

* forest tribal communities,

* agricultural societies,

* urban polities, and

* ascetic and tantric sects.

This inclusive adaptation created an internally diverse religious ecosystem unmatched in most centralized faiths.

A Polycentric Literary Tradition

Hinduism’s scriptural landscape-Vedas, Upanishads, epics, and Puranas-is polycentric, layered, and open-ended (Doniger 2009). The Puranas, in particular, evolved over nearly a millennium (Rocher 1986), functioning as encyclopaedias of myth, cosmology, and regional lore.

Other religions typically consolidate around a single authoritative scripture. Hinduism’s decentralized literary culture allowed for:

* multiple retellings of myths,

* new gods and goddesses,

* absorption of local deities, and

* continuous philosophical reinterpretation.

This facilitated an ever-expanding mythological universe.

Philosophical Elasticity: “The One and the Many”

The Indian philosophical tradition, especially the Vedantic idea that “Truth is one, sages call it by many names” (Rig Veda 1.164.46), provides a metaphysical foundation for multiplicity.

Different deities represent different aspects of the same ultimate reality (Brahman). Thus, the existence of numerous divine forms does not contradict monism-it expresses it. This philosophical openness ensures that new divine manifestations can be integrated without threatening doctrinal stability.

The Nine Goddesses of Navratri

Among the most vibrant expressions of goddess worship is Navratri, a nine-night festival celebrating the Navadurga-nine manifestations of the Goddess Durga. Each form is associated with a distinct cosmic function, spiritual principle, and psychological quality (Kinsley 1988).

The Nine Goddesses are:

* Shailaputri – Foundational strength

*Brahmacharini – Austerity and discipline

*Chandraghanta – Courage and serenity

*Kushmanda – Cosmic creation

*Skandamata – Nurturing motherhood

*Katyayani – Righteous anger and justice

*Kalaratri – Destruction of fear and ignorance

*Mahagauri – Purity and renewal

*Siddhidatri – Perfection and accomplishment

The Navadurga exemplify how ancient, Vedic, Puranic, and regional traditions merge seamlessly into a living ritual cycle, preserving complexity while sustaining coherence.

Conclusion:

Civilizational Resilience and the Iqbal Connection

The rich universe of Hindu mythology-full of devas, daityas, serpent kings, sages, river goddesses, fierce Shakta forms, and the Navadurga-is the outcome of a civilizational tradition defined by continuity, inclusivity, and philosophical openness. Unlike many world religions that streamlined their narratives under a single theological authority or displaced pre-existing beliefs, Hinduism evolved through an “accumulative” process. It absorbed the myths, rituals, and symbols of diverse communities across millennia, allowing multiple cosmologies and cultural memories to coexist without needing harmonisation.

This integrative capacity offers insight into a broader cultural resilience that has marked the subcontinent for over three thousand years. It resonates powerfully with Muhammad Iqbal’s celebrated line:

There is something in us that does not allow our identity to disappear.

The durability of Hindu mythological imagination-its ability to embrace plurality without losing coherence, to integrate new ideas without erasing old ones, and to preserve complexity without sacrificing vitality-captures precisely that Iqbal evokes.

It is this long historical continuity, nourished by inclusivity, philosophical elasticity, and an expansive literary tradition, that has allowed the goddess tradition and the vast spectrum of divine beings to remain central to the cultural and spiritual life of the Indian subcontinent today.

(The author is former Head of Computer Engineering Department in G B Pant University of Agriculture & Technology)

Trending Now

E-Paper