Parvez Dewan

As Hamida Banu Begum @ Maryam Makani [1527-1604] lay dying in the palace of her son, the emperor Akbar, she had but one wish. She wanted to take a last look at her personal, lavishly illustrated copy of the Ramayan.

Her husband Humayun was dethroned in 1540. The exiled couple travelled through the deserts of Rajasthan and Sind looking for refuge, and endured great physical discomfort. Therefore, some contemporary commentators argued that Ham?da had a strong emotional bond with Sita ji who, too, had to suffer privations when her husband was exiled. Hamida gave birth to Akbar in the third year of her exile, in which she apparently saw a parallel with Sita ji giving birth to her twins in exile.

Hamida had no Hindu ancestry. Both her parents were Muslims and her father was a Persian. Badayuni had completed his translation of the Ramayan only fifteen years before but the holy book was already being considered auspicious among Muslims of foreign extraction like she.

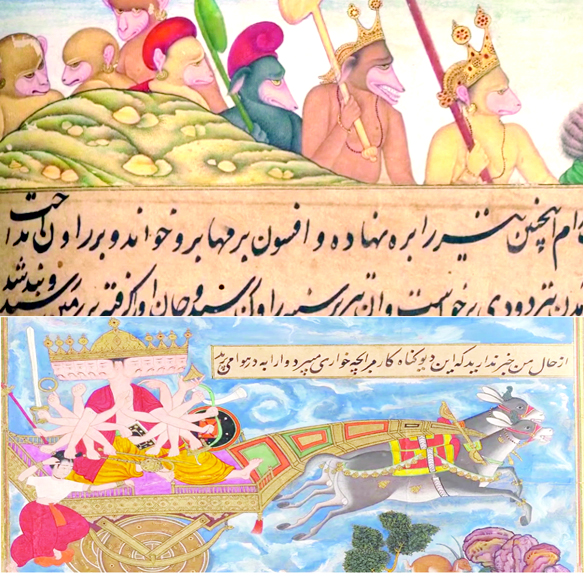

Akbar understood that Hindu readers expected their epics to be illustrated. So, he indicated to the translators 165 episodes that he wanted to be shown as paintings. This is what increased the cost of each copy.

At one stage Hamida’s copy was valued at 550 gold coins (mohurs). [In 2025, the estimated value of 550 gold mohurs, based solely on their gold content, is approximately Rs 4.87 crore.]

Since around 1690, according to Indian and European scholars of high credibility, this copy has been kept in the library of the Jaipur City Palace and is said to be still in excellent condition. In the 1980s, there was an ownership dispute within the erstwhile ruling family of Jaipur. So, a court ordered the holy book, and other treasures, to be locked inside a ‘strongroom.’ Visitors have not been able to read it ever since.

However, ‘one of the stars’ of the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, is Hamida Banu’s personal copy of The Ramayan. Readers of the Daily Excelsior are urged to watch on YouTubethe video ‘Manuscript Art: The Ramayana Epic with the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.’ It captures the beauty of this richly illustrated manuscript. Apparently, this copy was acquired from Sri Lanka. From all accounts this is more likely to have been the Queen Mother’s personal copy than the one in Jaipur, which no one has seen in ages.

Now that Persian- speaking Muslims of foreign extraction were able to read The Ramayan, a trend was triggered that continues to this day. In every generation or two, at least one Muslim has either translated the Ramayan afresh or written his, and in the 21st century, her, own, reverent retelling of the Ram Katha (the story of Ram).

Dr Ajit Pradhan, who has translated Persian and Urdu works into English, writes, “What is surprising is, there are twice as many Ramayans in Urdu as there are [Urdu translations] of Quran and Ramayan was translated into Urdu much before Quran was translated. There are over 100 Urdu / Farsi Ramayans.

Padma Shri Ali Jawwad Zaidi spent a lifetime seeking Urdu Ramayans in Indian libraries and archives. He discovered that at least three hundred Ramayans had been written in Urdu alone.

Zaidi, who knew Hindi and Sanskrit, initially funded his research independently while working for All India Radio and the Press Information Bureau. He later received leads and information from Ramlal Naagvi of Punjab and funds from the Birla Trust, enabling him to send questionnaires to universities and Urdu academies across India. After his retirement, Zaidi dedicated himself fully to this mission. Bal Anand of the Indian Foreign Service, a former Indian High Commissioner to New Zealand and 27 years younger than Zaidi, took him as his murshid (spiritual guru). He saw Zaidi as embodying “the highest virtues of all the faiths of mankind.” Anand recalled that Zaidi remained intensely focused on editing various Urdu Ramayan versions even in his later years, despite failing eyesight.

One such copy of the Ramayan is now preserved in Jammu.

Ramayan Nazam Khushtar, 1889

In 1955 there was a terrible flood in the Jammu district. Kalyanpur village was wiped out. The family of the Lahore University-educated AyodhyaNath Angara could not rescue their moveable possessions. The one valuable that they saved was the family’s most precious heirloom, the Ramayan Nazam Khushtar. This book was printed and published by Munshi Chiragh Deen and Sirajuddin at Rawalpindi’s Edgbaston Press in 1889. It is a Persian translation of Tulasi Das’ Ram Charit Manas.

Quite apart from the family’s devotion to this religious text, written by a Muslim, even in monetary terms its value far exceeded the total worth of a rural or even urban middle-class family’s immovable assets in 1955. A connoisseur from Sweden offered Angara’s son, Shyam Lal, Rs.10 lakh for this illustrated, block-printed book. The Angara family, which prized the holy book above all its other worldly possessions, refused.(At that time, a half-acre plot and mansion in Jammu city together cost less than Rs 50,000.)

The book was written by hand and includes miniature paintings of Sri Ram, Sri Sita, Hanuman ji and other characters of the epic.

The book made national news in 2011 when India Today and in 2012 NA Ansari credited its authorship, incorrectly,to the Dara Shikoh, whose younger brother Aurangzeb got him killed and seized the Mughal throne.

In 2000, a short snippet in The Milli Gazette mentioned Maulvi Imamuddin as the translator. Its editors seem to have better evidence because they have printed a facsimile of the first page of this holy book, at the top of which is the invocation ‘Bismillah ir Rahman ir Raheem.’

But the Muslims of Indonesia started translating the Ramayan and retelling the story of Lord Ram well before Akbar’s time and continue to do so to this day.

(The author is the founder of Indpaedia.com, India’s own free encyclopaedia. He has earlier served as Deputy Commissioner, Jammu-Samba; Secretary, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India; and Advisor to the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir)