Excelsior Correspondent

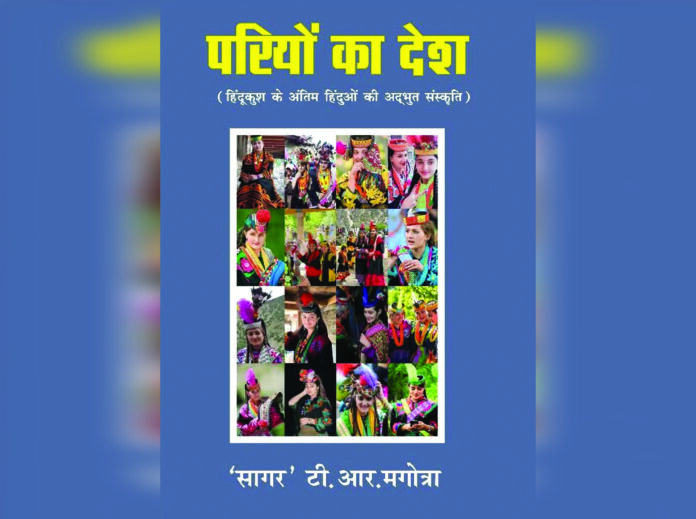

Book Review: Pariyon ka Desh (Hindi)

Author: T. R. Magotra ‘Sagar’

Publisher: Raveena Prakashan, C-316, 11-Ganga Vihar, Delhi-110094

Pages: 298

This book is about the Kalasha people, an indigenous tribe living in the Hindukush mountain range in the Chitral district of Pakhtoonkhva province, Pakistan, who have preserved their ancient Hindu culture and traditions despite being surrounded by Islamic influences. The unique culture is a blend of Hinduism, animism, shamanism, with some influences of Greeks and is known for its vibrant festivals, traditional music and colourful clothing.

This book has been divided into fourteen chapters, which are further divided into many sub-sections like culture, castes, marriage practices, their Gods and Goddesses, beliefs, festivals, geographical situations, livelihood etc.

Historically, the Kalasha community is considered one of the oldest indigenous communities in the region, with debated origins linked to Indo-Aryans or Alexander the Great’s troops. These valleys serve as a living repository of unique rituals, traditions and myths, drawing significant interest from historians and anthropologists.

The grandest of all is that Kalasha carry a romantic view of being the descendants of Alexander the Great. On the other hand, many believe that they are an indigenous tribe of the area of Nooristan also called Kafiristan (the land of Kafirs). The earliest notice of a claim to the ancient Greeks as Paropamisos was brought to Europe already in the 13th century by Marco Polo, the Venetian traveller, who reported in his famous book ‘The Travels of Marco Polo’ that the royal dynasty of Badakhshan descended directly from Alexander’s marriage with the daughter of Darius, and for that reason all the kings of that line called themselves Zulkarnein, in memory of their great ancestor. Polo’s report was confirmed over two centuries later by the emperor Babur-the founder of the Mughal imperial dynasty of India.

Yet the rulers of Badakhshan were not the only ones to claim descent from Alexander; rulers of Darwaj also claimed Greek ancestry, and many princes of Roshan, Shignan and Wakhan, and all the princes of upper Oxus (Amu River) made the same claim.

The second theory proposed by Gail Trail is that Kalasha descended not directly from Alexander’s armies, but from the armies of his General Seleucus Nicator who returned around 309 BC to re-conquer and resettle the area after Alexander’s death.

But the writer of this book has added a new dimension that they are the members of ancient Kamboja country, which was part of a great alliance of four ancient countries i.e. Gandhara, Kapisha, Balheek and Kamboja and through marriage alliances with Greeks a new culture developed in that region.

Kamboja state was one of the sixteen great Mahajanpadas in ancient India. It was a formidable warrior society known for its military prowess and skilled cavalry. This country did not end due to a single event or conquer but rather experienced a series of conquests by various empires and groups. The city of Kapisi (modern Bagram, Afghanistan), a Kamboja centre, was reportedly destroyed by Cyrus.

At present the Kalasha comprise a community living in the three small valleys of Birir (Biriu), Rambur (Rukmo) and Bumbret (Mumorete) in the District Lower Chitral. These three valleys span 456 square kilometres, known for their diverse natural forests like Pine, Chilgoza, Deodar, and a range of non-timber forest products crucial to Kalasha community livelihood. The community sustains a mixed mountain economy, blending agriculture (wheat, maize etc.) with livestock and indigenous knowledge.

Despite their rich resources, the Kalasha community faces formidable challenges threatening their survival: harsh terrain, adverse climates, unplanned tourism, limited livelihoods, cultural dilution and climate awareness gaps.

While the majority of the Kalasha have converted to Islam, they are primarily practitioners of the traditional Kalasha religion as they call it, which is a form of animism and ancestor worship mixed with elements from the ancient Indo-Aryan religion and mythology, but very little post-Vedic influences. Elements of the Kalasha mythology and folklore are closely related to the Vedic mythology, and its religion has also been compared to that of ancient Greece.

Kalasha culture and belief systems differ from the various ethnic groups surrounding them, but are similar to those practised by the neighbouring Nooristanis in northeast Afghanistan before their conversion to Islam. Richard Strand, a prominent expert on languages of the Hindukush region, noted the following about the pre-Islamic Nuristani religion: ‘Before their conversion to Islam the Nooristanis practised a form of ancient Hinduism, infused with accretions devolved locally; they worshipped a number of human-like deities who lived in the unseen world.’

The first historically recorded Islamic invasions in this region were by the Ghaznavids in the beginning of the 11th century. Taimur Lang has verified these facts in his memoirs. Nooristan had been forcibly converted to Islam in 1895-1896, although some evidence has shown that the people continued to practice their old customs.

During the mid-20th century an attempt was made to force some Kalasha villages to convert to Islam, but people fought the forcible conversion, and official pressure was removed, and the majority of them resumed the practice of their own religion. Nevertheless, some members of Kalasha have since converted to Islam, mostly as a result of marriages with Muslims.

The Kalasha are often referred to as Kalasha Kafirs or Kaale Kafirs (black Kafirs), because women wear black gowns embroidered with colourful stitching/designs, their native land is known as Kafiristan. Kalasha have been subjected to increasing incidents of killings, rape and seizure of their land. As per Kalasha people, forced conversions, robberies, and attacks endanger their culture and faith. The neighbouring Nooristani people of the adjacent Nooristan (historically known as Kafiristan) province of Afghanistan once had the same culture and practised a faith similar to that of the Kalasha, differing in a few minor particulars.

Every Kalasha village has altars dedicated to their Gods and Goddesses where animal sacrifices and rituals take place. Some Gods and Goddesses include Inder, Baluman, Sajigor, Krumai, Mahandeo, Nirmali, Imara, Jeshatak and Dizane, who is the great mother Goddess of Kalasha. Some Gods and Goddesses are from the Vedic period and some are Greek Gods, whom they worship.

In addition to their Gods and Goddesses, the Kalasha people also believe in fairies called ‘Vetrs’. These fairies are thought to be present everywhere and need to be pleased for obtaining good crops. During a ceremony, a fire is lit in the crop center, and offerings like juniper cedar, ghee and bread are made reciting a ritual.

In the Kalasha religion, they strongly believe in things being either pure or impure. Kalasha women spend their time in ‘Bashali’ during menstruation, because they are considered Pragata (impure) in Kalasha Dastoor (religion and tradition).

In the Onjeshta domain, there are high mountains, juniper, holly-oak, Markhor, goat, honey bees, altars, stables and men. In the ‘pragata’ domain, there are lower valleys, onions, garlic, sheep, hens, eggs, and Bashali (menstrual house), graveyard and women according to Kalasha Dastoor.

Linguist George Abraham Grierson has placed the Kalasha language in the ‘Dardi’ group of languages; the majority of the languages spoken in the Hindukush mountain range belong to the Indo-Aryan group. Modern Indo-Aryan descends from Indo-Aryan languages such as early Vedic Sanskrit, through Middle Indo-Aryan languages (Prakrits).

This book is throwing a light on various aspects of Kalasha community. It is a must-read book. Author born in village Gurha Slathian has eighteen published books in Dogri/Hindi to his credit.