Ashok Ogra

ashokogra@gmail.com

Some questions in public life simply do not lend themselves to straight answers. Politics, literature, and history often unfold in shades of grey rather than in neat columns of right and wrong.

As John Stuart Mill reminded us long ago, “he who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.” Many debates are too layered-shaped by emotion, memory, faith, and identity-to be settled by slogans or certainties.

It is in this sense that the continuing debate around Vande (or Bande, in Bengali) Mataram resists any single, tidy conclusion. It demands that we understand context, respect differing sentiments, and accept that a diverse country will inevitably produce diverse emotional responses.

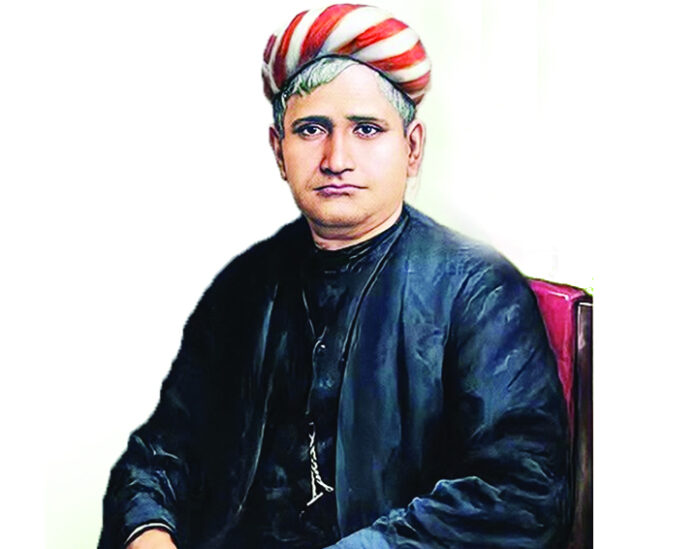

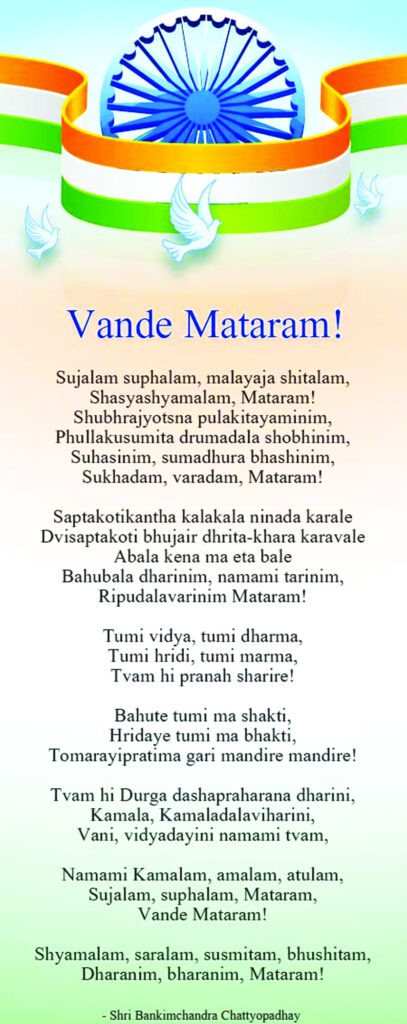

When Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay wrote the song in 1875, it began as a poetic vision of the motherland rather than a political manifesto. Few remember that Bankim initially penned an English version titled “Mother, I Salute Thee.” He later reworked it into Sanskritised Bengali, giving the song the elevated cadence by which it is now known. He included in 1881 in his novel Anandamath. The original poem ran to sixty-six stanzas.

The novel portrayed the rebellion of sanyasis against Muslim rulers during a period of famine and chaos. The song, placed within this narrative, carried an atmosphere of defiance mixed with spiritual longing. When published, it touched something deep in the Indian imagination. It quickly became a powerful symbol of the freedom struggle. Yet, for others, especially because of certain later stanzas with strong Shakta devotional imagery, the song also provoked hesitation.

My purpose here is not to pronounce judgment, but to place Vande Mataram in its historical and emotional context, allowing readers to arrive at their own conclusions.

Bankim conceived the song as a complete hymn, where devotion and patriotism were inseparable. To him, the motherland was not merely territory, but a living presence capable of awakening moral courage and sacrifice.

It was in 1937-when Jawaharlal Nehru was Congress President-that the song entered a more contentious political phase. Congress-led provincial governments, rather than any single central directive, encouraged or, in some cases, mandated the singing of Vande Mataram in schools. This move triggered objections, most notably from the Muslim League under Jinnah. The objections centred on compulsory singing and on the later verses that invoked a mother-goddess resembling Durga-imagery that many Muslims felt violated their religious beliefs. This fierce opposition of the Muslim community to Vande Mataram put the nationalist leadership (read the Congress party) in a quandary.

Sri Aurobindo provided philosophical depth to the song by describing Vande Mataram as “the mantra of India’s freedom.” He argued that its imagery was symbolic and civilisational rather than sectarian, and that dividing the song weakened its inner power. Nationalism, he believed, drew strength not only from laws and programmes, but from shared myths and symbols that stirred the deeper imagination. This view resonated strongly among revolutionaries and cultural nationalists. Leaders such as Bipin Chandra Pal, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and Lala Lajpat Rai used the song as a rallying cry against colonial rule, convinced that its portrayal of a motherland in bondage captured the emotional core of resistance.

Savarkar defended the full text as an expression of cultural nationalism, rejecting the idea that national symbols must be stripped of religious idiom to be legitimate. For reasons unknown, the RSS while not objecting to the singing of Vande Mataram- standardised its own prayer-“Namaste Sada Vatsale Matrubhoome”-as the closing ritual of the daily shakha. According to the scholars of the RSS, Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle, this was a conscious organisational choice aimed at creating a uniform, nationwide liturgy distinct from Congress-led nationalist practices.

Alongside this ran another thinking that admired the song deeply but resisted its imposition. Rabindranath Tagore was among the earliest to recognise Vande Mataram’s artistic brilliance. He sang it publicly, praised its purity, and believed it captured India’s soul with rare delicacy. His rendition at the 1896 Congress session helped turn the song into an emblem of the freedom movement. Yet Tagore consistently warned against nationalism hardening into ritual and coercion.

Subhas Chandra Bose approached the song not as a literary figure but as a revolutionary. For him and the INA, Vande Mataram was a source of courage-something that lifted tired spirits and strengthened resolve. At the same time, Bose was acutely sensitive to inclusiveness. Despite his affection for the song, he chose Jana Gana Mana as the INA’s marching anthem so that soldiers of every faith could rally without hesitation.

Gandhi, too, regarded Vande Mataram as pure and uplifting, but insisted that patriotism must be sung in freedom. His solution was characteristically simple: use only the first two stanzas, which contained no religious imagery, and never compel anyone to sing. As he repeatedly emphasised, ‘a song of freedom must itself be sung freely.’

A sharper critique came from the secular-revolutionary and constitutional camp. Bhagat Singh, an avowed atheist, rejected devotional nationalism altogether, preferring the secular cry of “Inquilab Zindabad.” For him, freedom was about social justice and reason, not sacred symbolism.

It was Dr B. R. Ambedkar who brought constitutional clarity to this concern. He respected the song’s historical role but warned that the state must never compel citizens to affirm symbols grounded in any one religious tradition. National rituals, he argued, must be inclusive, universal, and free of religious obligation.

Nehru echoed similar concerns. He admired the song’s emotional force but cautioned that enforced nationalism diminishes democracy. In a telling exchange, when Nehru expressed discomfort after reading Anandamath, Tagore advised him that while the first two stanzas could be used publicly, the rest should remain optional.

These differing voices-sometimes conflicting, but always sincere-came together in the Constituent Assembly through quiet negotiation rather than dramatic confrontation. Cultural nationalists such as K. M. Munshi, H. V. Kamath, and Alladi Krishnaswamy Aiyar argued that Vande Mataram had become the heartbeat of Indian nationalism and that its revolutionary legacy deserved honour.

Sardar Patel, personally moved by the song and mindful of its role in the struggle, nevertheless accepted that unity could not rest on symbols that troubled the conscience of any community.

The final settlement came on 24 January 1950, when Rajendra Prasad articulated the consensus. Vande Mataram, he declared, had played a historic role in India’s freedom struggle and would be honoured equally with the national anthem-but no citizen would be compelled to sing it. Jana Gana Mana would be the national anthem; the first two, non-sectarian stanzas of Vande Mataram would be recognised as the national song. It was a carefully balanced resolution, respecting tradition without sacrificing freedom.

In the end, the founders neither denied the song’s cultural resonance nor allowed it to become a test of loyalty. They affirmed a principle that remains relevant today: patriotism binds most strongly when it persuades, not when it is imposed.

When the demand arose to adopt Vande Mataram as the national anthem, a practical concern was also weighed. With its multiple stanzas and shifting metre, the song did not lend itself easily to a single, standardised musical score suitable for formal state or military occasions. Jana Gana Mana, by contrast-set to a precise composition was better suited to function as a national anthem that could be sung or played instrumentally with uniformity.

This diversity of interpretations and meanings is not a weakness but the very reason the song has endured. In a country as vast and layered as India, symbols survive not because they remain fixed, but because they adapt. Some questions in public life are not meant to be settled once and for all, but to be reflected upon with care. Vande Mataram is one such symbol-too important to dismiss, too complex to simplify. It is indeed sad that the enduring message of Anandamath is often overlooked. It was meant to be read as a moral reminder: that a nation survives not on symbols alone, but on character, responsibility, and the everyday, often unseen work of caring for the republic.

As Professor Sugata Bose, grandnephew of Subhas Bose, has observed, the song calls upon Indians to embrace it in a spirit of unity, not division.

Unfortunately, the ongoing debate in Parliament only underlines how fractured our politics has become. To the average citizen, it is evident that the real problem is not the song itself, but its politicisation.

(The author works for reputed Apeejay Education, Delhi)