Maj Gen sanjeev Dogra (Retd)

sanjeev662006@gmail.com

The road ends in a kind of silence that only mountains know. Beyond Kishtwar, past the last predictable bend and the last tea stall where someone still calls you “Saab” with the warmth of the plains the landscape begins to strip you of comforts. Slowly at first, then all at once. The air thins into effort. Your lungs negotiate every breath. The river below does not “flow”; it argues with the rocks. Even the sunlight feels altered. Sharper, whiter, almost unforgiving.

Try crossing from Kishtwar towards the Suru Valley today and you learn a simple truth: the Himalayas don’t allow casual ambition. They demand preparation. They punish vanity. They reward the disciplined. And they do it without drama. Just through physics, altitude, and weather.

Up here, distances lie. A ridge that looks “just there” can consume hours because the ground refuses to be easy. Loose scree that slides like sand under a boot, rock that bites into leather, sudden tongues of ice hidden in shadow, waiting for one careless step. Weather is not a forecast; it is a decree. A calm blue morning can collapse into a white squall by afternoon, and the cold does not arrive like a visitor, it descends like an order. The wind, constant and capricious, finds every gap in your clothing and, more importantly, every gap in your resolve.

And then you meet the people, and your respect deepens into something personal. Ladakh’s hardiness is not a slogan; it is a daily method. A farmer here plans like a logistician. A shepherd reads the sky like a navigator. Families ration and store with the seriousness of troops preparing for a prolonged winter. Their hospitality is practical: a warm cup placed before questions are asked, a firm insistence that you eat first and a quick glance at your layers. A reminder, never loud, never dramatic that the mountain is always the senior authority. Their resilience has a quiet tenderness too: they know hardship, so they do not waste kindness.

Suru, therefore, feels less like a destination and more like a classroom. It trains you without asking. It tests planning, stamina, humility. I learnt this not as a historian but as a practitioner. In 2019-2020, I commanded 8 Mountain Division, with our headquarters stationed in the Suru Valley. Living and operating here does something to command: paper authority loses its shine, and only quiet, dependable competence remains.

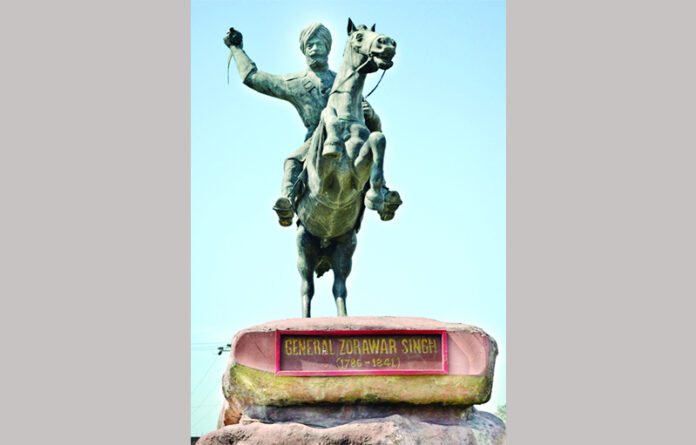

It also sharpens your ear for history, because in such geography the past is not “behind you”, it is beside you, present in routes, habits, and conversations. In those conversations, often with elders whose faces carried the weather one name surfaced repeatedly, spoken with familiarity rather than formality: General Zorawar Singh Kahluria. What struck me was not only that they remembered him; it was how they remembered him. Not merely as a conqueror, but as a commander of control-someone who knew that in the mountains, power without restraint becomes a curse that returns to cut your own supply line.

Nearly two centuries ago, Zorawar Singh, rising from rugged Dogra country and entrusted with authority in Kishtwar looked east toward the trans-Himalayan world and attempted what was, for his time, militarily unthinkable: to carry a fighting force into Ladakh and bring that strategic kingdom under the expanding influence of Jammu, under Raja Gulab Singh.

The strategic logic was clear enough to any frontier mind: routes, trade, influence, depth. But the Himalayas do not care for logic. They care only for readiness, resilience, and respect for their rules.

To imagine that march is to feel awe tempered by unease. Picture the column: soldiers and porters in wool and rough leather, breath pluming in frozen air, hands cracked, shoulders bruised, hauling their own weight and their ruler’s ambition up slopes where even sure-footed animals hesitate. Artillery and supplies broken down, redistributed, dragged forward by discipline and desperation. There were no satellite warnings, no modern medical assurance, no quick evacuation when lungs failed or frost began to eat the fingers. A misjudged crossing could swallow a file of men into silence. And yet the column moved, because one man at the front refused to allow the mountain to dissolve his force into panic.

This is where leadership in the Himalayas reveals its true shape: it is rarely theatrical. It is structural. It is the relentless, unglamorous machinery of keeping men coherent. Strict marching order, disciplined halts, systematic rations, enforced rest, attention to the weakest, and the steady insistence that fear will not be allowed to govern.

In the mountains, organisation becomes comfort. Discipline becomes warmth. Routine becomes courage. Zorawar’s first victory was not a fort taken; it was the preservation of cohesion in terrain designed to break cohesion.

When that exhausted, frost-nipped force descended into Suru, the campaign entered its most delicate phase. Here, the tangible enemy was only one part of the equation. The greater adversary was the land and the allegiance of its people. A hostile valley could turn a corridor into a gauntlet: ambushes, misinformation, vanished supplies, broken rear areas. Goodwill was not a moral luxury; it was the most critical supply line of all.

And this is where the human touch matters. Where history stops being only movement on a map and becomes a study of character. An army hardened by cold and hunger carries a latent capacity for cruelty. When survival feels urgent, temptation whispers: seize grain, commandeer livestock, “teach a lesson.” But cruelty is expensive in the Himalayas. One insult to dignity can travel across valleys faster than any messenger, turning villages into silent fortresses of opposition.

Zorawar Singh is remembered in Suru because his force, by the accounts that linger, did not arrive like a plague. Through strict discipline, he restrained looting and harassment, paid for supplies, and respected local customs and places of worship. Buying not just barley and firewood, but a rear that did not rise up to cut his throat.

Resistance did not vanish. Mountain warfare rewards the defender’s patience. Often the aim is not a dramatic decisive battle, but delay. Stretch the invader, thin his supplies, let weather become the primary weapon. And the Himalayan clock is seasonal: the season closes like a fist. Rations shrink. Fatigue accumulates. Winter waits above, impartial and merciless.

Here the campaign offers one of its finest leadership lessons: the difference between pride and purpose. There comes a moment when ego demands reckless momentum, advance simply to appear unstoppable. But the Himalayas punish such vanity with graves. Zorawar Singh chose consolidation. Securing defensible positions and weathering the brutal season, preserving the core of his force so that spring would find him intact rather than exhausted. In the high Himalayas, timing is not procrastination; timing is survival and strategy.

It is tempting to summarise what followed only in political terms. Submission, tribute, altered maps. But to view this story only as conquest is to miss the deeper instruction. The political outcome is a line in a textbook. The more enduring victory was over forces that defy flags and treaties: altitude, logistical impossibility, and the collapse of morale.

Those were silent victories; they don’t sing like a charge, but they decide whether any campaign has a future. In the high Himalayas, winning is not only about defeating an opponent. It is about defeating altitude, weather, fatigue, and the slow erosion of morale. The commander who masters these invisible battles ensures that the mission remains alive long enough for strategy to bear fruit.

That is why Zorawar Singh’s march is more than a historical episode. It is a case study in leadership stripped of ornament is relevant even today whether one leads soldiers, institutions, teams, or families. It reminds us that audacity must be the child of calculation, not the parent of recklessness. That logistics is strategy, not a back-office detail, because in thin air the supply line becomes the battle. It also shows that discipline is strategic compassion. Restraint protects civilians, secures routes, and ultimately shields one’s own men from backlash. Cultural intelligence is operational intelligence in mountain societies that are proud, observant, and with long memories. Above all, it teaches that patience can be an active weapon: the courage to consolidate and wait for the right season may be higher than the courage to charge. And finally, it underlines a timeless truth. Leadership in extremes is not about loud authority, but about visible presence and shared hardship, because men follow consistency more than rank.

When I look back at Suru from my own years of command, one thought returns with stubborn clarity: technology changes tools, not the test. Uniforms evolve. Weapons evolve. Radios and satellites shrink distances. Yet the mountains remain the same stern teachers.

And the people, the hardy, pragmatic, resilient people remain essential partners in any enterprise, their cooperation a force multiplier no technology can replace.

General Zorawar Singh’s true monument is not marble. It is route and wind. It is etched into the hard corridor between Kishtwar and Suru, into thin air that turns every breath into effort, into deep winter that punishes arrogance. It endures in the collective memory of communities who remember not only who arrived with power, but how that power behaved.

And as the Suru wind whistles its eternal tune through poplars and around the great massifs, it carries forward a question that transcends armies and borders: What is your personal Umasi La. Your impossible, necessary pass? What hard route are you willing to take, not for applause, but for a purpose larger than yourself? And when the storm finally hits, when comfort and certainty vanish and the column falters, will your leadership be loud and fleeting, or steady, visible, and humane enough that the land itself remembers it with respect?

Trending Now

E-Paper