India reclaims river rights

Anand Kumar

India’s revival of the Sawalkote Hydroelectric Project on the Chenab River in Jammu and Kashmir signals far more than a monumental infrastructural undertaking-it marks a decisive shift in India’s strategic posture and national policy. This 1,856 MW project, now the largest in the Union Territory, has emerged against the backdrop of a broader recalibration of India’s foreign, security, and water policies, driven in no small part by the recent suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan.

In the wake of the brutal Pahalgam terror attack in April 2025, which claimed 26 lives, India made the fateful decision to pull out of a treaty that had long been seen as both a cornerstone of regional water management and a symbol of Indo-Pak cooperation. However, for many in New Delhi, the treaty was never viewed as equitable. The IWT, brokered in 1960 under the auspices of the World Bank, had granted Pakistan control over the water of the western rivers of the Indus basin-namely the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum-while India retained rights to the eastern rivers. Although the treaty allowed India limited “non-consumptive” use of the western rivers, its provisions imposed strict limitations that constrained India’s ability to fully harness these water resources for hydropower, irrigation, and storage. With the suspension of the treaty-a response, according to Indian officials, to Pakistan’s continued support for cross-border terrorism-the strategic environment has irrevocably changed.

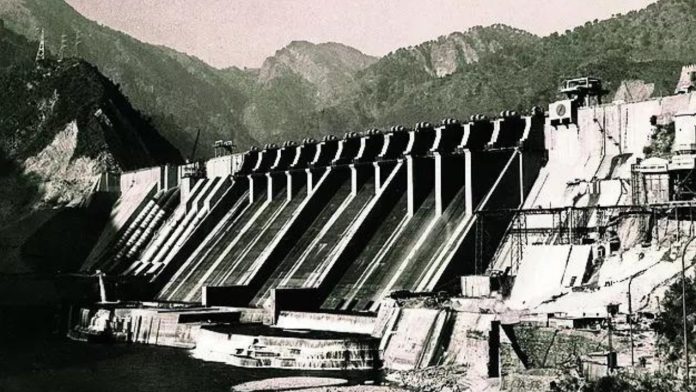

The Sawalkote project, conceived in the 1960s by the Central Water Commission, had long been a project in limbo, caught in a web of bureaucratic inertia, environmental and political concerns, and the limitations imposed by the IWT. Over the decades, the project struggled to find a clear path to realization. Diplomatic sensitivities, lengthy clearance processes, and the necessity of prior notifications under treaty obligations kept the project dormant. But with the treaty now effectively in abeyance, India is free to move forward. On July 29, 2025, the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) floated an international tender for planning and design work worth Rs 200 crore, with the bid submissions due by September 10. Declared a project of “national importance,” Sawalkote has been fast-tracked through an expedited clearance process that bypasses much of the previous red tape.

Once completed, Sawalkote is expected to generate roughly 8,000 million units of electricity annually, significantly contributing to regional energy security. More than a mere power generation facility, the dam will stand as a powerful assertion of India’s sovereign rights over its natural resources. No longer willing to be tethered to an agreement perceived as overly generous to Pakistan, India is charting its own course, one in which its strategic needs-for energy, water for irrigation, and domestic consumption-are placed at the forefront.

The suspension of the IWT is a watershed moment in the history of Indo-Pak relations and regional water diplomacy. For 65 years, the treaty was lauded as a beacon of cooperation between adversaries in a tumultuous region, but the recent decision to suspend it underscores a growing sentiment in New Delhi that generosity has been misinterpreted as weakness. In a recent parliamentary session, Union Home Minister Amit Shah condemned the treaty as “one-sided” and stressed that Indian farmers also deserve equitable access to river waters. This rethinking of water policy is not merely about economic or developmental considerations-it is deeply intertwined with India’s broader strategic calculus.

By suspending the treaty, India has not only liberated itself from bureaucratic constraints that once forced it into a position of submissiveness but also paved the way for a more assertive approach to water resource management. This shift enables India to move from symbolic “non-consumptive” uses of western rivers to direct, strategic exploitation of water resources, including storage, larger-scale hydropower generation, and expanded irrigation facilities. India’s actions serve as a stern warning: any support for terrorism, no matter how indirect, will be met not just with military or diplomatic countermeasures but with long-term policy shifts that strike at the heart of an adversary’s vulnerabilities.

For Pakistan, the implications of these developments are alarming. The Pakistani economy, particularly its agricultural sector, is heavily reliant on the water from the Indus system. Already, the consequences of recent water restrictions have become evident at Pakistan’s Marala headworks, where water inflows have reportedly dropped by as much as 90%. Such severe reductions can devastate water-intensive crops like paddy and cotton, undermining food security and economic stability. Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has even characterized the suspension of the IWT as an “act of war,” though his subsequent calls for dialogue indicate an awareness of the complexities involved in reversing decades of entrenched policy.

The Sawalkote project is just one element of a broader suite of hydropower initiatives that India now seeks to revive. Along with Sawalkote, other projects such as Pakal Dul (1,000 MW), the twin facilities at Kirthai (combined 1,320 MW), and several smaller projects totaling an additional 2,224 MW are being fast-tracked. Together, these projects are poised to deliver up to 10,000 MW of clean energy for Jammu and Kashmir, reinforcing the region’s energy independence and bolstering the national grid. Beyond energy generation, these initiatives are expected to enhance water security for several key Indian states, including Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Delhi-regions that stand to benefit considerably from improved irrigation and domestic water supplies.

This integrated approach to water and energy policy reflects a profound evolution in India’s strategic thinking. The government is no longer content to treat water, energy, and diplomacy as separate issues. Instead, it is leveraging natural resources in a comprehensive manner that simultaneously addresses domestic needs and sends a potent strategic message. Water and energy, historically viewed merely as developmental priorities, are now at the core of India’s national security apparatus. The ability to control and exploit these resources is being recognized as a critical element of strategic power, particularly in a region as water-scarce and geopolitically volatile as South Asia.

Critics of India’s new policy caution against potential environmental damage and the social costs associated with large-scale projects such as Sawalkote. Environmentalists and local communities have raised concerns about the ecological impact of dam construction, including the displacement of over a dozen villages and the relocation of an army transit camp. These issues are significant and require careful mitigation, yet many analysts argue that the strategic imperatives underlying these decisions override the expected challenges. After all, the alternative-remaining shackled by an increasingly untenable treaty while absorbing repeated terror attacks-is not viewed as viable by policymakers in New Delhi.

Moreover, the design of the Sawalkote project as a run-of-the-river scheme should alleviate some environmental concerns. Unlike large storage dams, run-of-the-river projects typically exert less pressure on local ecosystems by avoiding massive reservoirs and significant water retention. The objective is not to weaponize water or to cause undue harm downstream but simply to ensure that India can fully leverage its water resources for national development. By removing the artificial constraints imposed by an outdated treaty, India aims to achieve a more balanced and sustainable use of its natural endowments.

Ultimately, what we are witnessing is a profound redrawing of red lines in the subcontinent. For decades, India allowed the IWT to remain inviolate, even in the face of repeated provocations-wars, ceasefire violations, and acts of terrorism. That period of restraint has come to an end. The Sawalkote dam is not merely an energy project; it is a strategic statement. It declares that India’s security interests and its right to harness its own natural resources will no longer be subordinated to treaties that, in the eyes of many policymakers, are patently unfair. It asserts that India is prepared to recalibrate its policies systematically-using water and energy as tools of both development and deterrence-in response to the challenges it faces.

In a broader sense, India’s actions may well serve as a case study in the evolving role of natural resources in modern statecraft. Once considered mere drivers of economic growth and quality of life, water and energy are increasingly being recognized as potent symbols of national power. In today’s era of hybrid warfare, where physical borders coexist with cyber and economic frontiers, the control and strategic deployment of natural resources like water can serve as a formidable lever of power. The strategic recalibration underway in India challenges old paradigms and compels us to rethink the interplay between natural resources and national security.

India’s decision to suspend the IWT and move ahead with Sawalkote, along with several other hydropower projects, represents a bold gamble. It is a gamble that seeks to balance domestic developmental needs against long-standing regional disputes. It underscores a commitment to national self-reliance and asserts that the sacrifices incurred in the name of security and development will no longer be one-sided. Critics may continue to raise environmental and diplomatic concerns, yet the strategic imperatives driving these decisions are both clear and compelling.

In the end, the revival of the Sawalkote project is not merely a construction endeavor-it is a recalibration of India’s entire strategic framework. It symbolizes a nation determined to protect its interests, ensure sustainable development, and assert its rights in a region that has long been defined by contestations over water. As India embraces its newfound strategic resolve, the message is unambiguous: the age of passive acceptance is over, and the era of active, integrated power politics-where water, power, and resolve flow together-is here to stay.

The author is Associate Fellow Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies & Analyses (MP-IDSA)