R K Handa

ravindersaroj@gmail.com

When you signed a contract promising a “home in a residential colony,” how comfortable are you if that clause is quietly rewritten into “commercial zone with added floors and mixed uses”?

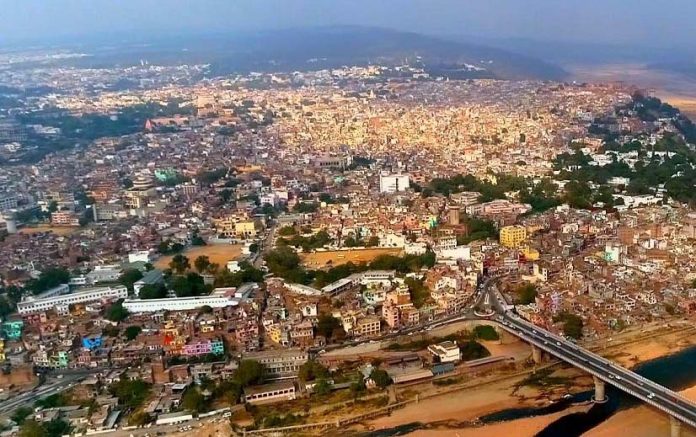

A home’s foundation, like that of a city plan, must be firm, not shifting. Yet, the Draft Jammu Master Plan 2032 (JMP-2032) proposes to introduce mixed land use, additional storeys beyond the standard Ground + 2, and composite land use in plotted residential colonies all without first putting in place detailed zonal plans and zoning regulations. Are we, then, constructing Jammu’s future on solid bedrock or on shifting sand?

According to the official Jammu Master Plan 2032 available on the Housing and Urban Development Department’s website (huddobps.jk.gov.in), existing residential uses already cover 57.63 sq km, or 8.83% of the city’s developed area. The gross residential density stands at 223 persons per hectare, far higher than the ideal 100-125 persons per hectare recommended for a city of Jammu’s scale. Should bold structural shifts precede a secure regulatory foundation? (By allowing ground plus four against originally planned ground plus two)

Imagine you purchase a plot in Channi Himmat , Trikuta Nagar or Gandhinagar colonies developed by the Jammu Development Authority (JDA) and J&K Housing Board for residential use. You expect serenity, children playing nearby, and a predictable neighbourhood. Yet, as reported by The Times of India (timesofindia.indiatimes.com), commercial activity is steadily creeping into these colonies under “change of land use” permissions even before the Master Plan’s final approval. If government agencies permit after-allotment breaches of residential purpose, are they not violating the implied contract with allottees and eroding the principle of insurable interest the very trust that underpins property ownership?( This has been challenged in supreme court of India and the court has ruled that such changes cannot be allowed after allotment and in absence of zoning plan and zoning regulations ).

If residential plots routinely morph into commercial spaces, what happens to living tranquillity?

Zoning regulations are like guardrails on a highway they keep development from veering off course. Yet Jammu has no approved zonal plans or zoning maps. The Unified Building Bye-Laws 2021 for J&K, notified by the Housing and Urban Development Department (nidm.gov.in), explicitly state that any change of sanctioned building use requires a Building Use Permit and those violations can render a building unauthorised. Without these guardrails, how do we ensure safety before allowing high-rise and mixed-use traffic to speed through residential lanes?

A balanced approach to mixed land use can work if applied selectively limited professional services (doctors, lawyers, CAs) or small trades (parlours, boutiques) confined to 25% of the covered area or 50 sq m, whichever is smaller. That’s the difference between adding a guest room and turning the house into a motel.

Even the draft Master Plan acknowledges that of the proposed net area, 46.427% (164.867 sq km) is residential, while 9.979% (35.439 sq km) is commercial (huddobps.jk.gov.in). If commercial and mixed uses are allowed without zoning clarity, we risk turning residential colonies into micro-cities of commerce, replacing peace with pressure.

In contrast, cities such as Pune and Bengaluru maintain stronger zoning regimes. For instance, the Pune Municipal Corporation’s 2017 Development Control Rules mandate clear separation between purely residential and mixed-use corridors (pmc.gov.in). Where such boundaries are enforced, residential character endures.

Jammu, by contrast, is already stretched thin. As reported by Business Standard (business-standard.com), there were 31 authorised and 21 unauthorised colonies under JDA jurisdiction as of 2018. Oversight is already fragile. Should we risk more complexity before ensuring discipline?

Rules without enforcement are like a car without an engine they may exist, but nothing moves forward lawfully. The Municipal Corporation of Jammu reportedly knows that several houses in residential colonies are being used fully or partly for commercial activity, but enforcement has been lax (constructionworld.in). If authorities knowingly overlook violations, doesn’t the Master Plan become a licence for informality rather than a tool for order?

Before steering the city’s future, shouldn’t the administration first take stock of every property in plotted colonies document them, photograph them, and verify their sanctioned use? A temporary moratorium on all change-of-land-use permissions until zoning regulations and enforcement mechanisms are operational would be prudent. The draft plan itself recognises the need to rationalise densities: low (?100 pph), medium (101-200 pph), high-medium (201-300 pph) and high (>300 pph) for a projected population of around 20.15 lakh in 164.87 sq km of residential area (huddobps.jk.gov.in).

Does it make strategic sense to hit the accelerator more floors, more mixed use before we’ve mapped the route?

Urban planning is like steering a ship. The course must be plotted, the hazards charted, and the crew aligned before the voyage begins. The Draft Jammu Master Plan 2032 might be a bold attempt to modernise the city, but without zoning clarity, legal transparency, and enforcement integrity, we risk running aground.

The question is simple yet profound: do we want plotted residential colonies that remain peaceful, predictable homes for families or are we willing to trade serenity for a noisy, hybrid skyline of commerce and chaos?

Trending Now

E-Paper