Ravi Rohmetra

ravirohmetra@gmail.com

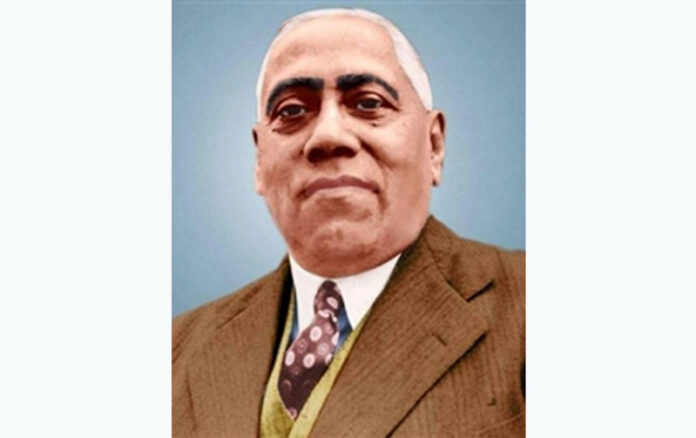

Mehar Chand Mahajan was born in a small village called Tika Nagrota in the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh and rose to become the Chief Justice of India, the highest honour the country could offer. Rejected at birth on astrological grounds, he was brought up in a Rajput peasant family up to the age of seven. Though brought home by his parents when he was seven years old, his father saw his face for the first time when he was twelve, under the guidance of astrologers and learned pandits, after due process of propitiating the gods.

After completing middle school in 1905, Mehar Chand moved to Lahore for further studies and graduated from Government College, Lahore, in 1910. He opted for an M.Sc. in chemistry and was taken in as a student demonstrator but, midway during the session, he was prevailed upon to switch to law. His father, Lala Brij Lal, a prominent advocate, had established an impressive legal practice at Dharamsala with a well-stocked library, and Mehar Chand was his only son; he was keen that Mehar follow his profession, where he could help and steer him to a good start in his career. Thus, in 1912, this young man, armed with his LL.B. degree, started practice at Dharamsala under his father’s guidance.

Mehar Chand took to his profession with almost fanatical zeal. As a young lawyer, he would study the briefs with meticulous precision, talk to the clients to establish the true facts, inspect the court records, consider in depth the legal issues involved and prepare his plan of action and strategy in detail. He soon moved from Dharamsala to the district courts of Gurdaspur, and later shifted to Lahore in 1918. Here he got opportunities for the display of his forensic abilities, and success following success took him to the highest rung of the ladder. Not only was he a keen practising lawyer, he was just as interested in its teaching. From 1922 he taught as a part-time lecturer at Law College, Lahore, for nine years.

Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir

The biggest challenge and achievement of Mr. Mahajan’s career was during the few months that he was the Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir from 15 October 1947 to March 1948. Though brief, this was a momentous period in the history of the country. Tribal raids were being organised by the Pakistan Government with the acquiescence of the British Governor of the Frontier Province. Ignoring the Standstill Agreement, Pakistan had stopped the import into Kashmir of essential commodities such as petrol, oils, salt, sugar, food and cloth. Infiltration into Kashmir along the areas touching Pakistan was being organised, and Poonch had been converted into a storm centre.

The Maharaja of Kashmir was undecided on the question of accession. Mr. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Prime Minister of Pakistan, was extremely keen that the Maharaja should accede to Pakistan. Lord Mountbatten advised the Maharaja not to accede to either of the Dominions without ascertaining the wishes of his subjects by referendum, plebiscite, election or by representative public meeting. The Maharaja and some of his advisers, going by the British declarations on the status of the states after independence, hoped for an independent Kashmir. In the state itself, the leaders of the Muslim Conference were keen that the Maharaja should accede to Pakistan, while the leaders of the National Conference desired accession to India. India, till then, had not shown any keen inclination either way; it would have welcomed the Maharaja’s accession to India but did not adopt any pressure practices to influence him. Sheikh Abdullah was keen to acquire power, but the Maharaja did not trust him. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of India, on the other hand, had enormous trust and faith in him, and with his support, Sheikh Abdullah was aspiring to become Prime Minister of the state, sidelining the Maharaja as a mere constitutional ruler.

Such were the tumultuous conditions in Kashmir when Mr. Mahajan took over the reins of administration as Prime Minister. He had earlier met Lord Mountbatten, Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Nehru and Sardar Patel to seek their advice. On 15 October 1947 he assumed the office of Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, and in less than two weeks, on 27 October 1947, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir formally acceded to India, thanks to the sincere, mature and pragmatic advice of Mr. Mahajan. At the same time, he ensured that before the formal agreement was signed, the Government of India’s troops landed at Srinagar by the morning of the 27th and started their military operations forthwith to counter the Pakistani attack.

To get the troops from India to move to Srinagar within 24 hours was an unprecedented achievement. On 26 October Mr. Mahajan flew to Delhi and went straight to Pandit Nehru’s residence, where Sardar Patel was also present. Mr. Nehru observed that troops could not be moved on the spur of the moment; necessary preparation and arrangements would take time. Mr. Mahajan, however, was adamant and ultimately stated, “Give us the military force we need. Take the accession and give whatever power you desire to the popular party. The army must fly to save Srinagar this evening or else I will go to Lahore and negotiate terms with Mr. Jinnah.” Such was the sense of duty and moral courage of this great man. As a result of the decision taken that morning, two companies of Indian troops were flown to Srinagar immediately and all available planes in the country were requisitioned for the purpose. This thwarted Mr. Jinnah’s plans for a massive two-pronged attack on Jammu and Srinagar.

Though a pre-eminent judge and jurist, Mr. Mahajan was an administrator of exceptional merit. During the communal frenzy that engulfed the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir, he maintained law and order with an extremely inadequate police force; he tried to restore some degree of confidence among the Hindu population of the state when their relatives and friends were being butchered and massacred by Pakistani soldiers masquerading as border tribesmen and by local Muslims armed by Pakistan, and he tried to help in the evacuation of Muslims wishing to go to Pakistan. His problem was that he did not have enough men in the state police force nor troops in the state’s Dogra contingent to effectively handle the law and order situation. With the promised support from India not forthcoming, he did the best that could be done within his very limited and meagre resources.

A constant irritant faced by Mr. Mahajan was the rather unethical modus operandi adopted by Sheikh Abdullah in acquiring totalitarian powers for himself in the state. He was keen that Mr. Mahajan should quit and that he be appointed instead as Prime Minister of the state with full administrative powers. To this end, he did everything he could. His pleadings with the Maharaja, however, were unsuccessful, since the latter did not trust him and was more than a little concerned about the communal slant in his thought and actions. On the other hand, the Maharaja had full faith and confidence in Mr. Mahajan’s judgment and sincerity. Sheikh Abdullah then tried to capitalise on Pandit Nehru’s keenness that the internal administration of the state be democratised and that he play an important role in it. His suggestion was accordingly placed before Panditji. However, the decision reached in consultation with Sardar Patel was that Sheikh Abdullah be designated as Head of Emergency Administration and Mr. Mahajan should continue to be the Prime Minister.

Now that Sheikh Abdullah had his foot in the state’s administration, he started methodically to grab as much power as he could, and his campaign for the ouster of Mahajan gathered further momentum. To discredit Mr. Mahajan, he started making false and malicious complaints to Pandit Nehru and even attempted to poison Mahatma Gandhi’s mind against him. Mr. Mahajan refused to submit to such unethical and unjustified criticism. He explained the factual position to Pandit Nehru, who regretted that he had been misinformed. To Mahatma Gandhi, he wrote of the circumstances in Jammu and Kashmir that led to communal violence. He also explained that the evacuation of Muslims from Jammu to Pakistan was being carried out under the protection of the Indian Army. The state police force was absolutely inadequate to enforce law and order when mass-scale communal violence erupted. He questioned Mahatma Gandhi: “May I ask you in the interests of justice and fair play and on principles of ahimsa whether in these circumstances you were right in what you said in the prayer speech…” (as reported in the Hindustan Times of 27 December 1947). He added, “It has hurt us (the Maharaja and himself) more because the speech was made without investigation and without giving us an opportunity to state correct facts, and on a hearsay version which was wholly one-sided and incorrect.” Mahatma Gandhi desired to meet Mr. Mahajan. The two had an hour-long discussion, and Mahatma Gandhi agreed with his analysis and conclusions. Sheikh Abdullah continued with his scheming manoeuvres, but Mr. Mahajan was not willing to be discredited on the basis of false complaints.

Meanwhile, at the suggestion of Lord Mountbatten, India had lodged a complaint against Pakistan in the United Nations Security Council on its open and blatant aggression, much against the advice of Mr. Mahajan and the Maharaja. The Maharaja finally agreed to it, since External Affairs was a subject on which the state had acceded to India. Pandit Nehru was now impatient to install Sheikh Abdullah as the Prime Minister of the state, as he was the head of the National Conference. Though the Maharaja was not willing to relieve Mr. Mahajan, he was finally persuaded by Sardar Patel to let him go, and Mr. Mahajan therefore left Kashmir at the beginning of March 1948.

A month later, he was asked by Chief Justice Kania if he would like to be considered for the Federal Court, since there was an urgent need for at least two more judges on the Bench. Mr. Mahajan agreed, though he knew that he was likely to be appointed Chief Justice of the East Punjab High Court. In the Federal Court, Pandit Nehru would have preferred Dewan Ram Lal, but the Chief Justice of India and Sardar Patel were of a different view, and eventually Mr. Mahajan was appointed.

On 1 October 1948, Mr. Mahajan took the oath of office as a judge of the Federal Court, which gave place to the Supreme Court when the Constitution of India came into force on 26 January 1950. The Supreme Court had been vested with very wide powers and jurisdiction under the Constitution, especially in protecting and guaranteeing the fundamental rights granted to citizens and residents. Some of the historic decisions of the Supreme Court in its formative years in which Mr. Mahajan participated related to the interpretation of such powers. Many of the laws in the statute book when the Constitution came into force interfered with the fundamental rights now guaranteed. The Supreme Court was suddenly burdened with applications seeking remedies against the invasion of fundamental rights, and as a result, it was able to weed out many of the laws on the statute book. In August 1950, Mr. Mahajan headed a Bench of the Supreme Court of Hyderabad to dispose of a number of cases pending before the Privy Council, which stood transferred to the Supreme Court. The Bench sat at Hyderabad for three months to dispose of the 382 cases which, it had been estimated, would have taken two or three years.

Chief Justice of India

In October 1951, Chief Justice Kania suddenly had a heart attack which proved fatal. The country lost its first Chief Justice at the comparatively young age of about 55. Mr. Justice Patanjali Shastri succeeded him. On his retirement, Mr. Mahajan took over as the Chief Justice of India on 4 January 1954. He took a Bench of the Supreme Court to Kashmir, as desired by the Home Ministry, to decide all cases transferred from the State Privy Council to the Supreme Court and, in just about a fortnight, cleared all pending cases. During his short tenure as Chief Justice of India, he tried, but without success, to introduce an all-India Bar judicial cadre of services, an all-India cadre of High Court judges and an all-India Bar.

Reorganisation of D.A.V. Institutions

After his retirement, the Managing Committee of the D.A.V. College Trust approached him to interest himself in its affairs. Mr. Mahajan had been associated with the D.A.V. College Trust and Managing Committee for many years. In 1919, soon after starting practice at Lahore, he was elected as Secretary of its Managing Committee and in due course became General Secretary and Vice-President. In 1936 he became President of the Managing Committee. He resigned as President on his elevation to the High Court but continued to be a member of the Managing Committee and of most of its important sub-committees.

Though he received requests to take over as Vice-Chancellor of Allahabad and Punjab Universities respectively, Mr. Mahajan preferred to devote himself fully to the revitalisation of the D.A.V. College Trust and Managing Committee and to rebuild all its institutions afresh in India. He had resolved to do his best to restore these institutions to their premier position in the educational field. He started a rehabilitation fund, undertook tours in and around Punjab for the collection of funds, reorganised various institutions and inducted dedicated people to manage them, and gradually and tirelessly rebuilt various D.A.V. schools and colleges at Jullundar, Amritsar, Ambala, Chandigarh, Hissar and Delhi. He continued to guide and direct the affairs of the D.A.V. institutions till the end of his life.

Trending Now

E-Paper