Manzoor Ahmed Naik

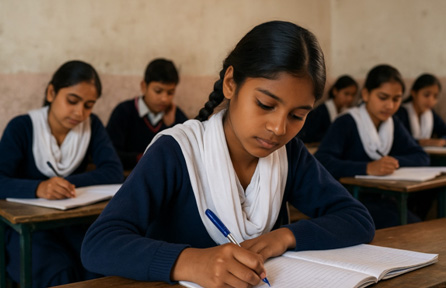

The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (RTE) remains one of India’s most progressive laws, guaranteeing free schooling for every child between 6 and 14 years. This framework brought millions into classrooms and nearly achieved universal enrolment at the primary stage. Yet, a glaring gap remains: students between 14 and 18 years, studying in Classes 9–12, are not covered. This leaves adolescents vulnerable to dropouts, precisely at the stage when education begins to shape livelihoods, employability, and social empowerment. Extending free education up to Class 12 and implementing RTE in letter and spirit is no longer a choice but a necessity.

Few regions in India have such a rich history of state-led education reform as Jammu & Kashmir. In the late 19th century, Maharaja Ranbir Singh and Maharaja Pratap Singh expanded modern schooling and introduced English as a subject. Maharaja Hari Singh went even further, enacting the Compulsory Primary Education Regulation in 1930, one of the earliest such initiatives in the subcontinent. Missionary schools in Srinagar and Jammu also laid the foundation for modern education. After Independence, J&K saw universities, colleges, and teacher-training institutes flourish. Yet, due to conflict, remoteness, and difficult terrain, the promise of education remained unevenly distributed.

The abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 brought all central laws, including the RTE Act, into force in Jammu & Kashmir. In principle, every child aged 6–14 now enjoys the same rights as children across India. But the challenge lies in translating these rights into ground reality. Reports still highlight gaps in infrastructure, teacher availability, transport, and inclusivity, especially in remote blocks like Budhal, Gurez, and border belts of Rajouri and Poonch. To honour the spirit of RTE, the government must ensure that no child is denied access due to poverty, distance, or gender.

The urgency becomes clear when one examines the numbers. According to UDISE+, India saw a decline of 3.7 million school enrolments in 2023–24, with sharp drops at the primary stage. If children are not retained at the secondary level, the situation will only worsen. Jammu & Kashmir today has over 24,000 schools and about 2.6 million students, with an annual per-student spending of nearly ₹1 lakh, one of the highest in the country. The UT’s education outlay is around ₹13,492 crore, yet issues of quality and equity persist. Rationalisation of schools has also led to a decline in government school enrolment, risking exclusion for children in remote hamlets.

Ensuring free schooling up to Class 12 will directly address the dropout crisis. Hidden costs—exam fees, uniforms, transport, digital access—discourage poor families from sending adolescents to secondary schools. For girls, lack of separate toilets and safe transport further compounds the problem. Extending free education would not only guarantee equity but also align with NEP 2020, which envisions universal schooling up to Grade 12 by 2030. In J&K’s conflict-affected and mountainous regions, this step could become a social stabiliser, reducing child labour, early marriages, and frustration among unemployed youth.

The RTE is more than a legal guarantee; it is a social contract. For J&K, implementing it in full spirit means ensuring functional schools in every neighbourhood, qualified teachers in every classroom, and safe, inclusive infrastructure for every child. Consolidation of schools must not force children to walk unsafe distances. Where geography poses barriers, the state must step in with free transport, residential facilities, and digital learning kits. Special attention must be paid to retaining girls in secondary education, with stipends, bicycles, and sanitary facilities becoming non-negotiables.

In the short term, Jammu & Kashmir should declare free education from Class 1 to 12 across all government schools, including exam fee waivers and transport support for remote areas. At the national level, Parliament should consider amending the RTE Act to extend the right up to 18 years. The UT must also create a Secondary Retention Index to track student progression from Class 8 to 10 to 12, ensuring no child slips through the cracks. Transparent reporting of per-student spending and better utilisation of Samagra Shiksha funds will strengthen accountability.

In 1930, Jammu & Kashmir was among the first in India to make primary education compulsory. Nearly a century later, it can once again lead the way—by becoming the first state or Union Territory to guarantee free education up to Class 12. The vision of NEP 2020, the promise of the Constitution, and the aspirations of J&K’s youth demand nothing less. Investing in secondary education is not merely an expenditure—it is the surest investment in peace, prosperity, and human dignity.