Parvez Dewan

Legend has it that one day; while gazing out from the glass room of his palace, Maharaja Ranjit Singh spotted a man struggling to manoeuvre his bullock cart across the River Ravi on a precarious pontoon bridge. The man was carrying a large object wrapped in red cloth.

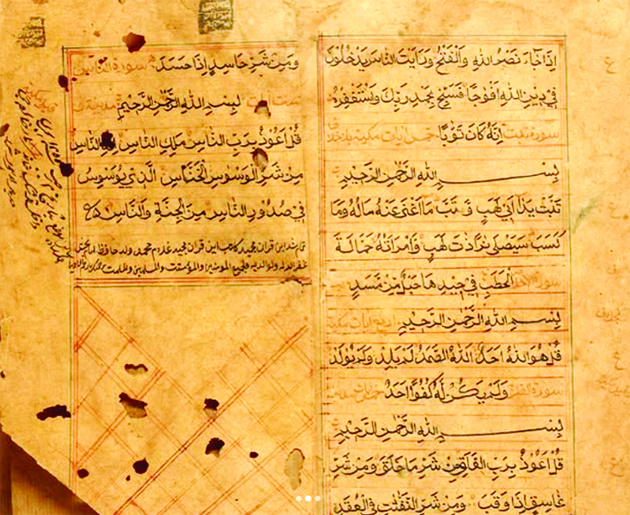

Curious, the Maharaja of Punjab inquired about him and was told that he was a calligrapher from Samrheyaal, transporting a meticulously inscribed copy of the Holy Quran-claimed to be nearly three feet wide-to Sind, hoping to present it to some wealthy patron in exchange for a sacred offering (hadiya).

Ranjit Singh asked for the calligrapher to be brought before him with the utmost respect, both for the man and the holy book. According to the Pakistani historian who narrated this incident, Sikh etiquette required that the Quran be carried on the head. When the calligrapher arrived, the Maharaja asked why he had chosen to take the Quran to Sind instead of bringing it to him-was it because he assumed a Sikh ruler would not be interested?

Ranjit Singh requested the revered faquirs Azeez ud Din and Noor ud Din to join him. The Holy Quran was placed on a clean sheet, as laid down in Indian traditions for sacred texts. When opened, it revealed Surah Yusuf. Azeez ud Din explained the Surah in Punjabi to the Maharaja, who called for his Munshi, Beli Ram, and told him to give the calligrapher an estate worth ?11,000 in Samrheyaal for the duration of his lifetime. The Maharaja thus acquired the magnificent manuscript and entrusted Azeez ud Din with the task of translating the Holy Quran into Punjabi.

In 1963, Khushwant Singh commented, “The story is apocryphal. But it continues to be told by Punjabis to this day because it has the answer to the question of why Ranjit Singh was able to unite Punjabi Mussalmans, Hindus and Sikhs.” Indeed, even in 2025, Pakistani historians kept asserting its veracity.

Apocryphal is a strong word for a story whose essence is true, even if it has distorted the chronology and confused the key figures. A hand-written Quran from the early 1800s, bearing the Gurmukhi seal of Maharaja Ranjit, was and probably still is housed in the Lahore Toshakhana. However, it is not as wide as in the legend.

The Punjabi translation of the Holy Quran, too, exists. The Maharaja’s grandson, Sardar Jagjot Singh, commissioned a limited edition of three hundred copies, which were published on April 1, 1882, and gifted them to his friends. In 2025, the Sabri Kutub Khana in Karachi offered a copy for sale.

In 1911, Sant Vaidya Gurdit Singh Alomhari, a Sikh from the Nirmala Sect, translated the Quran into Punjabi using the Gurmukhi script. Two Hindu businessmen, Bhagat BuddhamalAadatliMevjat and Vaidya Bhagat Guranditta Mal, along with a Sikh, Sardar Mela Singh Attar Wazirabad, financed Sardar Buddh Singh of Shri Gurmat Press, Amritsar, to print a thousand copies of the 782-page edition. Out of devotion to the auspicious Islamic number 786, these Hindus and Sikhs added four pages of advertisements.

Ranjit Singh was also the custodian of eight relics associated with Prophet Muhammad, as well as some sacred belongings of Hazrat Fatima, Hazrat Ali, and Imam Hussain. The Prophet’s belongings included a green turban with a cap (Amama Sharif) and a green cloak (Jubbah-i-Mubarik). These relics were passed down from Timur and the Mughals, who entrusted them to a Raja of Jammu for safekeeping, before they reached Ranjit Singh’s clan. The aforementioned Faquir Noor ud Din catalogued these relics. It is said that the Nawab of Bahawalpur offered Maharaja Ranjit Singh one lakh rupees for the shoes, but he declined.

Mahruk, son of Raiq, was the first known Hindu king to seek a translation of the ‘Shariat (law) of Islam’ into ‘the Indian language’ (Al-Hindia). He ruled over Ra, a kingdom in ‘central Kashmir’. In AD 883, he sent this request to the prefect (roughly: governor) of al-Mansura, whose name was Abdullah, son of Umar, son of Abdul-Aziz. (Then and till almost five hundred years later Sanskrit was the language of literate Kashmiris.)

There are at least ten places in the world named Al-Mansura, but this one appears to be the one in undivided India, near present-day Shahdadpur (Sind).

Abu Muhammad al-Hasan, son of Amr, son of Hammawayh, son of Harârh, son of Hammawayh of Najîram, told this story in Basra to Buzurg bin Shahryar, the captain of a Persian ship, who recorded it in his famous travelogue, Ajaib-ul Hind (The Wonders of India). He said that Abdullah, the prefect, ‘conveyed the request to a man who was then in Mansura, a man from Iraq, a superior mind, of fine intellect, a poet, who had been raised in India and knew its various languages.

‘This man put into verse everything necessary for the knowledge of religion, and his work was sent to the king. The prince found this admirable and asked Abdullah to send him the author. The man was therefore sent to the king: he remained there for three years, then returned to Mansura. The prefect questioned him about the sovereign of Ra.

‘The man said, “[The Kashmiri king] asked me to translate the Quran into Indian [Sanskrit] for him. Which I did.

‘”I was at Surah Ya-Sin, and I translated for him the words of God: ‘Who gives life to rotten bones? Answer: He who produced them the first time, He who knows the whole of creation.’ [The Kashmiri king] was then seated on a golden throne encrusted with precious stones and pearls of incomparable value.

‘”Tell me that again,” he said. I repeated it. He immediately descended from his throne and took a few steps on the ground, which had been sprinkled with water and was damp. Then he pressed his cheek to the ground and wept, so that his face was soiled with mud. “That is He,” he said to me, “the Master to be worshipped, the first, the ancient, the one who has no equal!”

‘”He had a private room made for himself and retired there under the pretext of important business, but in reality to pray secretly, without anyone knowing anything about it. On three occasions he bestowed upon me 600 pounds of gold.”‘

(The entire Ajaib-ul Hindis available in French on archive.org as Livre des Merveilles de l’Inde.It was writtenbyBozorgfils de Chahriyar de Ramhormoz,and translated into French by L. Marcel Devic. I translated pages 24-26 into English using Google Translate.)

Next week we shall see that Maryam Makani, the Persian mother of Emperor Akbar, was even more emotionally attached to her lavishly illustrated copy of the Ramayan, which her son had got translated by Badayuni. Indian Muslims made at least a dozen translations of the Ramayan after that, while Indonesian Muslims produced even more.

The family of Jammu’s Ayodhya Nath Angara was in the national news in the year 2000 because it possesses a copy of a Ramayan translated by a Muslim.

(The author is the founder of Indpaedia.com, India’s own free encyclopaedia. He has earlier served as Deputy Commissioner, Jammu-Samba; Secretary, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India; and Advisor to the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir)