Ashok Ogra

Dalit cuisine is not about choice; it’s about accessibility. Their food practices are a result of deprivation, not abundance. Even today, most Dalits navigate meals not as a matter of taste, tradition, or celebration-but as a question of survival.

As one Dalit writer, Anita Bharti, pithily puts it, “The upper-caste minimum is our maximum.”

I came face-to-face with this unsettling reality during a conversation that began warmly, reflectively, but left a deep impression on me.

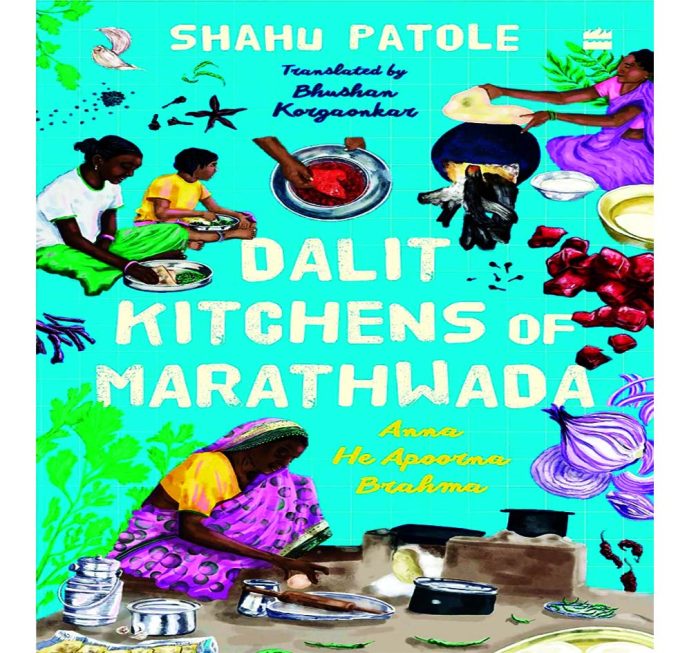

I met Shahu Patole the author of much acclaimed book ‘Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada’ at the Jaipur Literature Festival earlier this year. Expecting a discussion on regional variations or perhaps culinary culture viewed through a sociological lens, I was instead led into a world I had neither experienced nor fully imagined. That single interaction-and later, the book itself-influenced me more deeply than I had anticipated.

Perhaps that’s because of where I come from.

As a Kashmiri Brahmin, I grew up in a cultural setting where caste-as it manifests in much of India-was virtually absent. Kashmiri society was historically divided along religious lines, not fragmented into caste hierarchies. Terms like “impure,” “untouchable,” or even the notion of “separate kitchens” were alien to our vocabulary. We never had to confront the daily violence of caste. It was not part of our lived reality.

That explains why ‘Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada’ revealed a world I had never encountered-not even in the margins of my upbringing. I had naively assumed that food was a great equalizer, a universal act of sharing. The book showed me how wrong I was. It spoke of denied ingredients, segregated utensils, and the humiliation wrapped into everyday meals-not as distant history, but as current lived experience.

What emerges from reading the book is that food is not just what we eat-it is who we are, where we belong, and how we are perceived? Whether through caste in India or class in Western societies, cuisine reflects deep-rooted structures of power, identity, and aspiration. Recognizing this helps us understand not just eating habits, but also the underlying social dynamics, and in the case of Indian Dalits, of inclusion, exclusion, and resistance.

‘Dalit’ refers to the over 16% of Indians historically excluded from the Hindu caste system and relegated to menial, hereditary occupations with no scope for upward mobility. Though un-touchability was outlawed in 1947, caste-based exclusion continues to persist across different regions – though not as sharp as it used to be. The term ‘Dalit-meaning “broken” or “scattered”-was first used by Jyotirao Phule and later championed by B.R. Ambedkar. It was further politicized by the Dalit Panthers in 1972 as a symbol of anti-caste assertion.

Denied access to land, markets, and communal kitchens, Dalits have had to make do with what remained-scraps, discarded parts, and coarse grains. Their culinary traditions have emerged from this exclusion, eating beef, pork, wild greens, and offal not by preference but by compulsion. These methods have evolved into rich food heritages, yet their cuisine carries the deep scars of stigma and shame, and remains marginalized in both popular culture and academic study.

No wonder, Indian food taboos divide not only humans from gods but also upper castes from oppressed communities. The Brahmin obsession with satvik food-devoid of meat, garlic, onion, or root vegetables-is projected as morally superior, while Dalit and tribal diets, born out of scarcity and survival, are dismissed as impure.

Therefore, from what we eat to how it’s cooked and who serves it, every layer of food culture is shaped by centuries of social stratification.

Shahu Patole has been bold in arguing that in India, food is never just food-it is memory, identity, status, and most critically, caste. His book is a manifesto of remembrance, dignity, and defiance.

The issue is not whether bee larvae are nutritious or jowar rotis are fashionable, but why some are mocked for what they eat while others are applauded.

Shows like Master Chef India and critics like Vir Sanghvi promote a sanitized, upper-caste version of Indian cuisine-glossy thalis and dairy-laden desserts-while ignoring the food of the oppressed.

Another Dalit writer, Chittibabu Padavala, elaborates on this point by asserting that in India, food is far more than sustenance-it is a social identifier shaped by caste, hierarchy and purity politics. “The push for vegetarianism-especially when backed by state coercion, vigilante violence, or digital food policing-is not about health or climate alone, but about enforcing Brahmanical norms across society.”

One wonders whether Shahu Patole is familiar with the large sections of Brahmin communities-Kashmiri, Bengali, Assamese, etc.-who are non-vegetarians.

Needless to mention, that Hitler was vegetarian and therefore food habits are not indicators of one’s moral character.

The irony is stark. The second-largest meat-eating population in the world is now being subjected to culinary uniformity. The myth of a unified Indian cuisine-by attempting to erase Dalit food practices from literature and media-is bound to fail.

Coming back to Shahu Patole, his book, originally published in Marathi as Anna He Apoorna Brahma, documents the food customs of the Mahar and Mang communities of Maharashtra. The work serves both as cultural archive and political critique. He offers recipes for dishes made from every part of the animal-bones, blood, intestines, bee larvae plucked from walls, and the epiglottis of the goat-all treated as delicacies. A dish made from dill easily foraged in the village is common, as are onions toasted on an open flame, and chutneys made from fat chilies pounded into a fiery mash with salt.

When I asked Shahu if bee larvae is a good source of protein, and if bhakris provide good nutrition, he was indignant. “It doesn’t matter,” he insisted. “That’s not what people were thinking when they foraged. It was what was accessible, and it was what was cooked. These analytical frameworks that assign one meaning to each dish are luxuries our communities never had.”

Patole notes, “We all know the plates of the upper castes, but our meals remain in the shadows.” His work brings those shadows into visibility.

While India faces twin challenges of malnutrition and lifestyle disorders, dietary debates often ignore the needs and practices of working-class Dalits, whose food choices are shaped by physical labor and economic constraints.

Ironically, Dalit food-once reviled-is now being appropriated by elite restaurants. Rakti, pork dishes, even red ant chutney are today marketed as “exotic delicacies” without any acknowledgment of their roots. Economic class and changing health trends now also influence diets, with affluent groups embracing coarse grains once associated with deprivation.

Take the case of millets transitioning from the plate of the poor and Dalits to a health fad among the urban elite. Therefore, unless policy correctives are made, the poor are being priced out of their own heritage.

In recent decades, as Dalits too have sought upward mobility, some have begun to abandon their own food customs and adopt upper-caste vegetarianism. But this erasure also risks losing cultural identity and continuity.

That this truth has remained invisible to someone like me-privileged by birth and geography-is exactly why it must be spoken about, and the book ‘Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada’ by Shahu Patole read.

(The author works for reputed Apeejay Education Society, New Delhi)

Trending Now

E-Paper