Prof. Ravij Seth

citag@iimj.ac.in

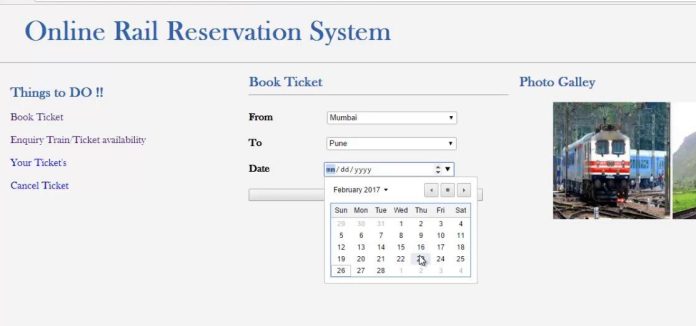

India’s railways are often celebrated as the country’s lifeline. Every day, this vast network carries millions of passengers, providing affordable, accessible, and relatively sustainable mobility across an enormous geography. It is the only mode of transport that can combine scale, reach, and affordability in a way that connects both metropolitan hubs and remote hinterlands. Yet, despite this formidable presence, the railway ticketing system suffers from a structural limitation: it is largely designed for direct journeys alone. In practice, this means that when no seats are available on a direct train, passengers are left stranded or compelled to find inefficient and stressful workarounds. At present, digital platforms-whether the official IRCTC portal or private aggregators such as MakeMyTrip, RedBus, and EaseMyTrip-restrict bookings to point to-point routes. When direct berths are unavailable, passengers are pushed into second best options: purchasing waitlisted tickets, hoping for last-minute Tatkal quota releases, or approaching divisional railway offices for Emergency Quota allocations. For many, these stopgap measures bring stress, uncertainty, and frequent cancellations. Others abandon the railways altogether, shifting to air or road travel. The result is both a personal inconvenience and a systemic leakage of demand away from the railway network. A small subset of resourceful passengers attempts to circumvent this problem by constructing connecting journeys themselves. For instance, a traveller unable to secure a direct Jammu-Lucknow ticket might instead purchase Jammu-Delhi and Delhi- Lucknow tickets separately, using Delhi as the transfer hub. This practice, however, comes at a cost. It requires managing multiple Passenger Name Records (PNRs), absorbing the risks of delays, and coordinating layovers without institutional support. A single late-running train can derail the entire plan. Ironically, railway employees do not face such constraints, since they are entitled to break-journey passes that legitimize such connections. The burden thus falls disproportionately on ordinary passengers, who must assume the role of informal travel schedulers. Some partial solutions exist. Private platforms such as eRail.in have experimented with a “via” feature that suggests possible connections. Yet such tools stop short of integrating real-time ticket availability or enabling bookings across multiple legs. Even IRCTC, the backbone of Indian railway reservations, does not provide functionality to seamlessly book a connected journey under a single PNR. The gap between information and execution remains wide, leaving passengers to stitch together fragments at their own risk. This is in sharp contrast to global best practice. In the United States, for example, Amtrak routinely displays both direct and connecting routes within the same interface. A traveller from New York to Harrisburg is shown not only direct trains but also the option of a connecting route via Philadelphia. The booking is integrated, the seat availability synchronized, and the responsibility of coordination assumed by the system rather than the passenger. Such models demonstrate that the idea is neither conceptually novel nor technologically infeasible. For India, the opportunity lies in adapting the hub-and-spoke model, long established in aviation, to the railway sector. Airlines allow passengers to book multi-leg journeys under a single ticket, with synchronized layovers and protected connections. A similar model in railways would allow passengers to book, say, Jammu-Delhi-Lucknow as one journey, with a single PNR, coordinated schedules, and guaranteed seats. The benefits of such a reform would be far-reaching. From the passenger’s perspective, it would reduce uncertainty, remove the burden of juggling multiple bookings, and increase confidence in rail travel. For the railways, it would improve seat utilization across corridors, provide stronger incentives to maintain punctuality, and retain passengers who might otherwise defect to road or air. For the broader mobility ecosystem, it would represent a decisive step toward building a genuinely integrated, multimodal infrastructure in which rail remains the backbone. Of course, the challenges are not trivial. Synchronizing timetables across multiple trains, integrating real-time seat availability, and designing intuitive user interfaces demand a robust technological backbone. But India is better placed today than ever before to attempt such an innovation. With the government’s emphasis on digital transformation, customer-centric reforms, and modernization of Indian Railways, the time is ripe to test this idea through carefully designed pilot projects. High-traffic corridors such as Delhi- Lucknow, Mumbai-Hyderabad, or Chennai-Coimbatore, characterised by dense passenger volumes and frequent services, would be ideal candidates. The pathway forward may also lie in public-private collaboration. Start-ups and established travel-tech firms could partner with IRCTC to build user-friendly booking systems, while Indian Railways ensures schedule alignment and operational feasibility. Such partnerships would distribute developmental costs, leverage diverse expertise, and promote a culture of co-creation in India’s public transport sector. The business case is compelling. A connecting-train booking system would not merely enhance convenience; it would unlock suppressed demand, increase ridership, and generate additional revenue. Much as airlines benefit from hub-and-spoke efficiencies, railways could optimize occupancy and network utility. More importantly, such a reform would showcase digital innovation in public services-an example of how technology can be leveraged to humanize infrastructure and place the citizen at the centre of design. 3 The larger message is clear: railway ticketing in India must move beyond a narrow transactional approach and evolve into a comprehensive travel solution. Passengers do not simply seek to buy tickets; they seek reliable journeys, free from the stress of uncertainty and the fear of disruption. If Amtrak can provide American passengers with the option of integrated connections, there is no structural reason Indian Railways cannot. In many ways, the absence of a connecting-train booking system is symptomatic of a wider inertia in institutional design. For too long, passengers have shouldered the responsibility of improvising connections and bearing the risks of failure. It is time for the system itself to absorb that responsibility. The introduction of a connecting-train booking system would represent more than a technological upgrade. It would symbolize a shift in philosophy-from viewing passengers as passive consumers of a rigid system to recognising them as active stakeholders deserving of flexibility, convenience, and care. This is an innovation whose time is overdue. If adopted, it would modernize India’s mobility landscape, reaffirm the centrality of railways in the national transport system, and set a benchmark in customer-centric governance. For a network so often described as the nation’s lifeline, the next step is clear: to not just carry passengers, but to carry them with confidence.

(The author is Prof. of Practice, IIM, Jammu)

Trending Now

E-Paper