T N Ashok

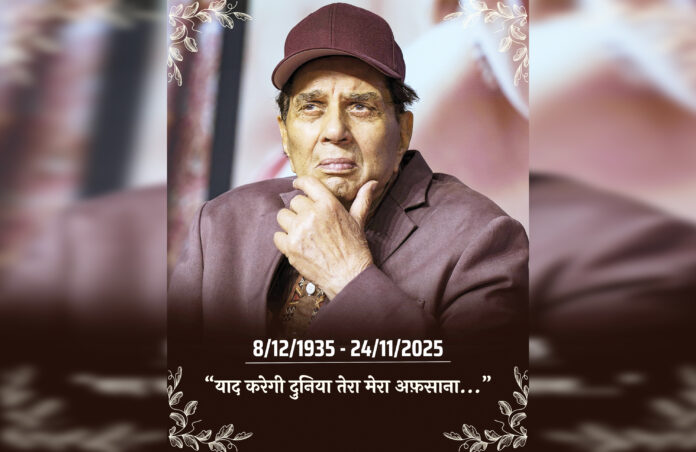

When Dharmendra breathed his last on November 24, 2025, at the age of 89, something intangible yet profound died with him. It wasn’t just the loss of one man, however legendary. It was the final, irreversible closing of a chapter in Hindi cinema that can never be rewritten-a chapter written in celluloid dreams, muscular heroism, and an authenticity that today’s green-screen spectacles can never replicate.

With his passing, the last towering pillar of Bollywood’s golden era has crumbled. The gallery of immortals-Ashok Kumar, Dev Anand, Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, Shammi Kapoor, Shashi Kapoor, and the bridge generation’s Sanjeev Kumar, Vinod Khanna, Vinod, Mehra, and Rajesh Khanna-have all departed now.

Dharmendra was the final guardian of an age when cinema was about presence, not pixels; about raw charisma, not CGI enhancements; about stories that touched the soul, not algorithms that track eyeballs.

The Hindi film industry will continue. Movies will be made. Box office records will be broken. But something irreplaceable has been lost-a connection to the very DNA of Indian popular cinema, to a time when stars were not manufactured by publicity machines but were born from the sheer force of talent and personality.

What makes Dharmendra’s death particularly poignant is the recognition of what the industry failed to acknowledge during his lifetime. Here was a man who delivered over 300 films across six decades, who transformed every genre he touched-action, romance, comedy, drama-with an ease that made the difficult look effortless. Yet he never received the Filmfare Best Actor trophy that his work so richly deserved. The Lifetime Achievement Award they handed him in 1997 felt like a consolation prize, a pat on the back for someone who deserved a standing ovation.

Consider Satyakam (1969), directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee. As Satyapriya, Dharmendra delivered what critics now recognize as one of the finest performances in Hindi cinema-a man wrestling with conscience, integrity, and disillusionment in a corrupt world. The film won the National Award for Best Hindi Feature, yet Dharmendra’s towering central performance went unrecognized. Perhaps he made it look too easy. Perhaps the industry, dazzled by his physique and charm, couldn’t see past the “He-Man” exterior to the nuanced actor within.

Then there was Phool Aur Patthar (1966), where he portrayed a man grappling with redemption and harsh realities with a depth that belied his action-hero image. In Anupama (1966), working again with Mukherjee, he brought sensitivity and restraint to a role that demanded emotional intelligence rather than physical prowess. These performances revealed layers that audiences and critics too often overlooked.

Even in his most celebrated work-Sholay (1975)-Dharmendra’s Veeru was a masterclass in balancing machismo with vulnerability, humour with heartbreak. Watch the scene where he contemplates suicide on the water tank, his drunken bravado masking genuine despair. That moment encapsulates everything Dharmendra could do: make you laugh, make you cry, make you believe.

And Chupke Chupke (1975), that delightful comedy where he played a botany professor masquerading as a driver, showcased his impeccable comic timing and intellectual wit. Here was the macho hero proving he could deliver Shakespearean-style comedy with grace and intelligence.

The numbers tell a story the awards never acknowledged. Out of those 300-plus films, 94 recovered their investments, 74 were declared hits, including seven blockbusters and thirteen super-hits. In some peak years, he delivered multiple successes while juggling an impossible workload. He remained relevant when others faded, transitioning from leading man to character actor without losing his star power.

Yet the mathematics that truly matters cannot be quantified. How do you measure the impact of a smile that could light up a screen? How do you calculate the value of a screen presence that could make mediocre films watchable and good films unforgettable? How do you assign numbers to the way he made audiences feel-the young women who swooned, the men who wanted to be him, the families who found in him the perfect blend of strength and sensitivity?

Dharmendra’s death arrives at a moment when Hindi cinema is in the midst of a profound transformation. The industry he helped build-where storytelling was king, where character trumped spectacle, where songs were woven into narrative rather than inserted as commercial breaks-has given way to a new paradigm.

Today’s Bollywood is dominated by the Khans-Shah Rukh, Aamir, Salman-who brought their own revolution, combining old-school star power with modern marketing savvy. Alongside them, actors like Hrithik Roshan and Anil Kapoor represent a transitional generation, one foot in the past, one in the present.

Now emerges the yuppie generation-Rajkummar Rao, Vicky Kaushal, Vikrant Massey, alongside Deepika Padukone, Alia Bhatt, Kiara Advani, Kriti Sanon, and Yami Gautam. They are immensely talented, bringing fresh sensibilities and new narratives. They navigate streaming platforms as comfortably as cinema halls. They understand social media, content creation, and the global marketplace in ways Dharmendra’s generation never needed to.

But something has been lost in translation. The new cinema is often technically superior, visually stunning, narratively ambitious. Yet it lacks a certain warmth, a human connection that actors like Dharmendra provided simply by existing on screen. Today’s films are made with precision; yesterday’s films were made with passion. Today’s stars are managed; yesterday’s stars simply were.

Dharmendra’s personal life played out like a Bollywood melodrama-two marriages, two families, six children, thirteen grandchildren, and a patriarch who somehow held it all together through sheer force of personality and, perhaps, genuine love. His marriage to Prakash Kaur at nineteen gave him four children, including Sunny and Bobby Deol, who carried forward the family’s cinematic legacy. His later marriage to co-star Hema Malini, controversial and tabloid-fodder for years, produced two more daughters.

What strikes one now, in retrospect, is not the scandal but the humanity. Here was a man who refused to abandon either family, who lived between two worlds, who somehow maintained relationships that should have been impossible. His first wife, Prakash Kaur, remained dignified throughout, never courting publicity, simply holding her family together. Hema Malini, the glamorous Dream Girl, accepted an unconventional arrangement for the sake of her children.

The fact that it took nearly thirty years for Esha Deol to meet her father’s first wife speaks to the complexity of the arrangement. Yet when that meeting finally happened-Esha touching Prakash Kaur’s feet, seeking blessings-it symbolized something beautiful: reconciliation, acceptance, the triumph of family over ego.

In that sense, Dharmendra’s life mirrored the very films he starred in-messy, complicated, sometimes contradictory, but ultimately guided by the heart.

With Dharmendra’s passing, Hindi cinema loses more than an actor. It loses a living bridge to its own history. He worked with the legends, learned from them, and in turn became one himself. He witnessed the industry’s evolution from the studio system to independent production, from black-and-white to colour, from single-screen theatres to multiplexes, from film to digital.

He remembered when actors took trains to outdoor shoots, when film sets were collaborative playgrounds rather than corporate enterprises, when a song sequence could be improvised on the spot if the mood struck. He embodied a time when stardom was earned through years of work, not engineered through a single viral moment.

The younger generation of actors-talented as they are-have no memory of that world. They cannot tell stories about working with Bimal Roy or Guru Dutt, about the craftsmanship of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, about the wild creativity of Nasir Hussain. Those stories die with Dharmendra.

Fittingly, Dharmendra’s family orchestrated his funeral with the same dignity he brought to his craft. They declined to turn it into the spectacle that other star cremations have become-no jostling cameras, no celebrity photo opportunities, no vulgar displays. It was a private goodbye to a public man, a final act of respect for someone who gave everything to his audience but deserved something for himself at the end.

Perhaps that decision, more than anything, captures the difference between then and now. Dharmendra belonged to an era that understood the distinction between public and private, that knew some moments were too sacred for commodification.

The sets are quieter now. The last of the giants has departed, leaving behind a changed industry, a grieving family, and millions of fans who grew up with him. School children today may not know his name, may not have seen Sholay or Chupke Chupke, may not understand what made him special.

But for those who remember, for those who witnessed his magic, the loss is profound. It’s the loss of certainty that someone out there still remembers how things were, how things could be, how cinema at its best could make you feel completely alive.

Dharmendra-the He-Man, the romantic hero, the versatile performer, the flawed father, the loyal husband to two wives, the patriarch of a dynasty-is gone. But every time someone discovers Satyakam, every time Sholay airs on television, every time a young actor tries to balance strength with sensitivity, his spirit endures.

The cameras have stopped rolling. The lights have dimmed. But the legend, mercifully, lives forever in the only place it ever truly existed: on screen, where Dharmendra remains eternally young, eternally charismatic, eternally the man we wanted to be or wanted to love.

Hindi cinema has lost its last He-Man. The silence he leaves behind echoes louder than all the noise of the new age. A soul has gone out of Hindi cinema but a rhythm of life he created in the 70s will shine for ever on the celluloid for a generation that adored him and the survivors of that generation will adore him watching reruns of his movies. (IPA)