Squadron Leader Anil Sehgal

Bhajan Singh is a Dogra from Ram Nagar, and presently works as a waiter at the Jammu Press Club.

I placed my order with him speaking in Dogri. He instantly warmed up to me and lamented that very few patrons speak to him in Dogri. “They like to speak in Hindi and Punjabi. May be, sometime, in a mix with English. But, rarely in Dogri.”

Similar complaints the Punjabis make in modern Punjab where inhabitants like to speak more of Hindi and English than Punjabi.

Jammu Jottings

However, that was not the scene we witnessed in Lahore. In that part of erstwhile Indian Punjab, the Lahoris, comprising 98 percent Muslims, speak Punjabi with natural and discernible pride.

In Lahore, if you speak Punjabi, you integrate with the locals irrespective that you are an Indian, a Hindu or a resident of Jammu and Kashmir, to top it up. That is the power language wields over religion.

As you speak of culture, language automatically comes into focus. Culture and literature are interwoven with the language we speak.

Let us take another illustration. In the erstwhile East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) the majority of population is Muslim. As a part of Pakistan, Urdu was their national language. But, almost the entire population spoke Bengali, not Urdu !

Bengali newspapers and magazines sold in larger numbers than periodicals in the national language Urdu.

Bengali language gave the East Pakistanis their sense of unity and identity. It was Bengali alone that bound all east Pakistanis together, something which religion failed to do. The result was the rise of people in unison and liberation of Bangladesh.

It seems that the battle for official recognition of Dogri language was more political than emotional. Not many Dogras like to converse in their mother tongue, even after seven decades of living in Independent India.

I recently visited Tanishq showroom in Jammu and spoke to the salesman in Dogri. I received little attention. The scenario changed dramatically as I chastened him in fluent English ! Thereafter, the gentleman made sure that I was pleased and well attended to.

Let me contrast this situation to what I saw in Uttar Pradesh way back in the sixties. I studied in the cities of Meerut and erstwhile Allahabad in the early to mid sixties.

These cities are hard-core Hindi belt dwellings. In schools, our medium of instruction was Hindi. It was “bhautik shastra” and “rasayan shastra” in place of physics and chemistry. Biology was called “jeev vigyan” and mathematics was “ank ganit”.

Hindi was the ruling language of Uttar Pradesh in the real sense. We all spoke fluent Hindi in our conversations amongst friends in school or the mohalla cricket playground.

In the markets, the shopkeepers, rickshaw pullers, doctors, teachers, everyone used real good, almost chaste by Jammu standards, Hindi language. It was not Hindi laced with Urdu, Persian, English or Punjabi words that we come across in the City of Temples.

There were no good mornings or good nights uttered exchanged between friends. It was always “shubh prabhat” and “shubh ratri”. We all took pride while using Hindi in our lives.

Especially we, the students, were proud of our love for Hindi, which somehow reflected our love for the country too. Nobody was ashamed of employing Hindi as the lingua franca for our day to day living.

It was not that we did not study English. English was a full fledged subject of 150 marks in the high school curriculum, just like Hindi, science or mathematics. As I returned to my motherland Jammu for further studies after the high school, there was a drastic change I faced. The college education was imparted in English medium, in Jammu.

My plight was pathetic, to begin with. Those days, it used to be a rare honour to score near 70 percent marks in high school or matriculation examination. All first division holders were seated in the front rows in strict order of precedence. So was I.

While delivering lectures, the teachers expected the front benchers to respond fast whenever he put a question to the class. In a similar situation, Prof Ramesh, asked me to define acceleration, while teaching us physics. I gave blank looks because I did not understand what was I asked, in the first place !

I knew the definion of “vegvriddhi” as acceleration was taught to us in Hindi medium. Nevertheless, I overcame this predicament soon enough.

Not only I picked up formidable conversational ability, I even excelled in English debates and also became editor of the English section of the college magazine.

I had spent my schooling years in the Hindi belt thousands of kilometres away from the Dograland. So, I felt it was imperative that I updated my knowledge and practice of speaking Dogri.

Therefore, I would make deliberate efforts to pick up colloquial vocabulary of Dogri from friends like Narinder Bhasin who enjoyed speaking Dogri.

In fact, Narinder sang melodious folksongs for me. Little did I know then what fate had planned for me and that I would eventually marry one of the tallest singers of Dogri !

But, I noticed that the students In our college did not converse in English. They conversed in workable Punjabi with a smattering of Urdu and Dogri, amongst themselves. Hardly anyone conversed in Dogri, though lot many students came from traditional Dogra families.

I don’t think situation is any different even after fifty years. As I visit the college now, I find almost similar treatment given to Dogri even today. The university is no different. Nor are the bazars and the malls in the city. Nowhere people converse in Dogri.

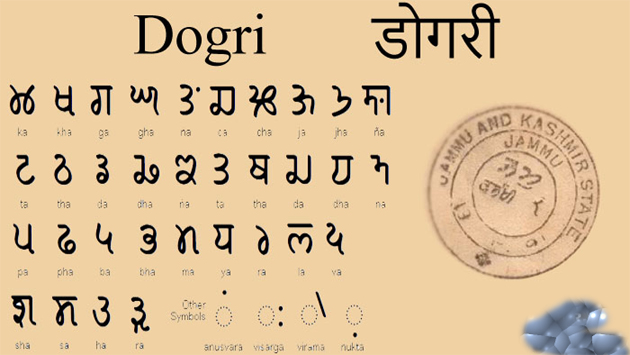

On 2 August 1969, Dogri was recognized as an “independent modern literary language” of India. It is one of the official languages of the Indian Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir.

On 22 December 2003, in a major milestone for the official status of the language, Dogri was recognized as a national language of India in the Indian constitution. But, the first daily newspaoer of Dogri was not published until 18 December 2007.

Today, Dogri may be alive through the annual Sahitya Akademi awards or in the library books of the Dogri department of the University of Jammu, but it is certainly not alive in the minds and hearts of the people whose ancestors fought concerted battles for her official and literary recognition.

Do you realise why Urdu is still alive in India inspite of the religious bigotry that it is an islamic language, although there is steady decline in the number of those who can read or write it’s script ?

It is alive because, knowingly or unknowingly, deliberately or unmindfully lot many Indians use it in their daily affairs, without realising they are speaking Urdu. Speaking is the key word here.

Look around and we find that all across the nation, people in all the states speak their mother tongues with pride ; be it Bengal, Tamilnadu, Kerala or Orissa. Or, for that matter, Sikkim, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh or Andhra Pradesh.

All these states, the native languages are popularly spoken by the people who like to read their daily capsule of news in the newspapers of their mother tongue only.

What can be worse than the remarks of the editor of Jammu Prabhat, the first ever Dogri daily newspaper of Jammu, Surinder Sagar, “Even Jammu’s people, the Dogras don’t like Dogri anymore. They don’t tell their kids to speak or learn Dogri. The language is disappearing from towns, cities and districts”.

If Dogras wish their mother tongue to survive and prosper, they will have to make sustained efforts to speak the language more and more. Remember, only those languages remain alive in which people make their day to day conversations.

As I write this elegy for the language, I find that culpable nonchalance of Dogras themselves is the real cause for the sustained and steady decline, and eventual demise of Dogri in the foreseeable future.