Prof Ramni Gupta

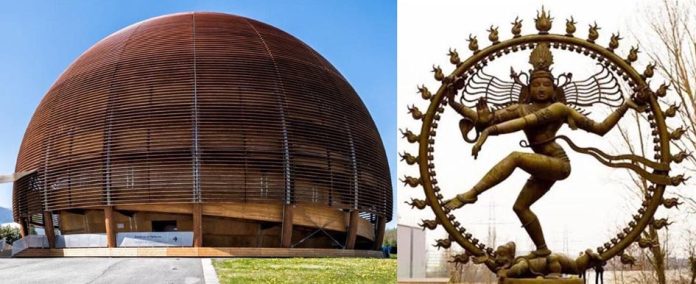

CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, stands as one of the world’s premier scientific institutions, dedicated to uncovering the basic building blocks of the universe. CERN’s journey began in the post-World War II era and has since evolved into a global centre for scientific discovery and international collaboration. It is based in Meyrin, a western suburb of Geneva, on the France-Switzerland border. CERN is an official United Nations General Assembly observer and is one of the most renowned scientific institutions in the world with a mission to explore fundamental questions in the field of physics: What is the universe made of? What forces govern the behaviour of matter? It studies the tiniest particles that make up everything around us, trying to understand how they work and what happened at the moment of the Big Bang, a widely accepted theory describing the creation of the universe.

The Birth of CERN (1949-1954) After World War II, Europe faced the challenge of rebuilding not only its cities and economies but also its scientific community. In 1949, a group of European scientists, including Nobel Prize winner Louis de Broglie, began advocating for the creation of a European laboratory dedicated to nuclear physics. In 1952, at the European Council for Nuclear Research (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire), scientists from 11 countries met to discuss forming a collaborative organisation, and on September 29, 1954, the CERN convention was ratified, and the organisation was officially established, with Switzerland hosting its headquarters in Geneva. While CERN initially focused on nuclear research, it soon expanded its focus to include particle physics,

First Accelerators (1957-1980) One of the CERN’s first achievements was the construction of its first particle accelerator, the Synchrocyclotron (SC), which started operations in 1957. Particle accelerators are the big, sophisticated machines that produce and accelerate beams of charged particles, such as electrons, protons, and ions, of atomic and subatomic size. Following the SC, CERN built the Proton Synchrotron (PS), which began operating in 1959. With a ring 628 meters in circumference, the PS was, at the time, the highest-energy particle accelerator in the world,

Super Proton Synchrotron (1980s) In 1983, CERN achieved one of its first major scientific breakthroughs when experiments at the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) led to the discovery of the W and Z bosons. These particles are responsible for mediating the weak nuclear force, one of the four fundamental forces in the universe. Bosons are particles that carry energy and forces throughout the universe.

Large Electron-Positron Collider (1990s) In the late 1980s, the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP) was built. LEP was the largest electron-positron collider ever built, with a circumference of 27 kilometres. It operated from 1989 to 2000, and its experiments confirmed many aspects of the theory, including the number of families of neutrinos. Neutrinos are some of the most mysterious particles in nature, capable of passing through the Earth like it wasn’t there. These particles are often called the “ghost particles” as they barely interact with any other particle.In 1989, CERN computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web to help researchers share data across different locations. Berners-Lee’s invention revolutionised global communication and transformed the way we access and share information today.

The largest energy collider LEP was dismantled, and its tunnel is used to make the home for the world’s largest collider operational in the world at the moment. In 2008, CERN inaugurated the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the largest and the most powerful particle accelerator ever built. With a circumference of 27 kilometres and housed in a tunnel 100 meters underground, By smashing protons together at these high energies, the LHC allows scientists to recreate conditions similar to those that existed just after the Big Bang,In 2012, CERN made history when it discovered the Higgs boson (commonly known as God particle), a particle that gives everything. The discovery, made by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at the LHC, confirmed the mechanism that gives particles their mass. In addition, handling the massive data generated by the LHC experiments has led CERN to pioneer advances in data processing and distributed computing.

Global Cooperation and Collaborations CERN is a shining example of international collaboration with scientists from over 100 countries working together. The workforce here represents a microcosm of global diversity, fostering a vibrant, inclusive environment that values people from all backgrounds. The code of conduct for mutual respect and the common scientific goal of knowing the fundamentals of nature reinforces its values of professionalism, respect, and integrity and provides clear guidelines for fostering a respectful workplace where diversity is celebrated.

While many countries are embroiled in political, economic, or cultural conflicts this particle physics laboratory stands as a beacon of peaceful collaboration. CERN has grown from its 12 founding nations to include 23 member states, with numerous associate and observer countries. India’s collaboration with CERN began in the 1960s. In 1991 India became an observer state and in January 2017 an associate member of CERN. An associate member has a voice in CERN’s decision-making processes and also allows Indian industries to bid in its contracts.

CERN’s collaborative culture has some key policies, such as believing in open science and thus sharing its findings freely with the global scientific community. Its open data policy and collaborative publications reflect its commitment to transparency and the collective advancement of knowledge. Diversity and inclusion policies at CERN promote gender balance, cultural diversity, and equal opportunity. CERN’s outreach efforts aim to inspire the next generation of scientists and promote public understanding of fundamental physics. It runs a range of education programs aimed at students and teachers, including hands-on workshops, summer schools, and teacher training courses.

As CERN looks ahead, it continues to expand its research capabilities. Plans for the Future Circular Collider (FCC), a successor to the LHC, are already underway. The FCC aims to be four times larger and significantly more powerful than the LHC with aim to study dark matter, antimatter, and the mysteries of the early universe and extra dimensions beyond the ones we know. CERN at 70 shows how far we’ve come in understanding the universe, yet it reminds us there’s so much more to learn. With its commitment to diversity, collaboration, and safety, CERN remains a cornerstone of scientific progress and a symbol of what can be achieved when nations unite in pursuit of knowledge.

(The author is Professor of Physics, University of Jammu Member of the ALICE experiment at CERN, Deputy Spokesperson of ALICE-STAR India Collaboration)

Trending Now

E-Paper