Kanvi Joshi

In a world saturated with images, filters, and screens, beauty has transformed into more than a passive attribute. It is no longer something one is simply born with or withoutit has become a relentless pursuit, a craft, a performance, and for many, a burden. The modern self is not only seen but must be seen as beautiful. It must be fashioned, curated, and refined to align with social ideals that are neither natural nor neutral. These ideals are deeply embedded in the structures of power that shape our collective gaze. The desire to be beautiful, far from being a purely individual preference, is profoundly social. We learn to want beauty because society teaches us that to be beautiful is to be visible, valued, and worthy.

Desire for beauty is not a spontaneous or personal inclination it is a socially conditioned response to cultural norms and expectations. From a young age, we are exposed to what is considered attractive through television, cinema, advertisements, and now more than ever, social media. This saturation constructs a shared visual vocabulary of desirability, with specific features and body types elevated as universal ideals. In this environment, wanting to be beautiful is not simply about aesthetics; it is about conformity, social inclusion, and even survival in professional and interpersonal spheres.

Beauty is a social construct, shaped by the dominant values of specific historical and cultural contexts. Different societies at different times have glorified different featuresfairness in one context, curviness in another, thinness in yet another. But these standards are not arbitrary; they are linked to hierarchies of race, gender, class, and even caste. In our globalised world, beauty is increasingly standardised around Eurocentric idealslight skin, slim bodies, straight hair, symmetrical features, and youthfulness-excluding a wide range of natural diversity. Those who do not or cannot align with these ideals often experience marginalisation, ridicule, or invisibility.

What often goes unnoticed is that beauty functions as a kind of social currency. It opens doors, earns admiration, and garners rewards. Research consistently shows that conventionally attractive people are more likely to be hired, promoted, or perceived as competent and trustworthy. In a modern world where individuals are expected to treat themselves as brands, beauty becomes a form of capital. It is no longer a luxury but a necessityparticularly for women, who are often judged more harshly on appearance than men. For many, staying beautiful is a full-time job.

But looking beautiful is not a simple task. It demands immense labour physical, emotional, financial, and psychological. It requires hard work, patience, money, resources, and knowledge. One must learn what products to use, what trends to follow, what workouts to do, and which foods to avoid. Achieving and maintaining beauty is a commitment that demands willpower. From skincare routines and makeup techniques to dieting, cosmetic procedures, and fitness regimes, every aspect of the body becomes a site of work. This effort is often masked by the language of “self-care” or “empowerment,” but underneath it lies discipline a discipline that sociologist Michel Foucault would describe as self-surveillance and regulation.

Foucault’s ideas are particularly relevant when we consider how beauty norms operate as systems of control. Individuals internalise these standards and begin to monitor, evaluate, and correct their own bodies. The rituals of beautification waxing, contouring, straightening, whitening become daily acts of self-policing. While these practices can offer a sense of agency or joy, they also reinforce the very norms that restrict us. The body becomes both the canvas and the cage an expression of selfhood but also a site of conformity.

At the core of this performance lies the socially structured desireto be admired, desired, and ultimately, accepted. But this desire is not organic; it is manufactured and monetised by a global beauty industry worth billions. This industry survives by creating new insecurities and then offering products to fix them. From anti-aging creams to skin-lightening lotions and body sculpting treatments, there is always something more to buy, something more to do. The message is clear: you are never quite enough as you are.

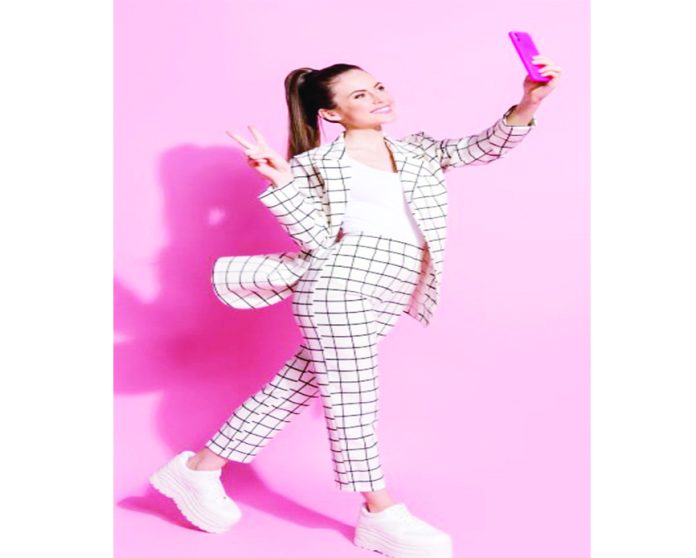

Social media has turbocharged this dynamic. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok have turned beauty into performance art. Through curated selfies, edited reels, and algorithm-pleasing poses, individuals display their fashioned selves for public consumption. Erving Goffman’s theory of the presentation of self takes on new meaning here, as users constantly manage impressions and seek validation. Likes and comments become metrics of social worth, turning the face and body into marketable assets. In this realm, beauty is no longer just a personal achievement-it is public content.

And yet, in this landscape of relentless visibility and competition, moments of resistance also emerge. The body positivity movement, anti-colourism campaigns, and non-binary fashion trends challenge dominant definitions of beauty and push for more inclusive representations. However, even these efforts are not immune to co-optation. Corporations often commodify rebellion, turning critical messages into commercial slogans. A protest becomes a product line. A demand for change becomes a trend.

To become beautiful today is not merely to apply makeup or dress well, it is to participate in a complex choreography of desire, discipline, and display. It is to navigate between freedom and conformity, between empowerment and pressure. Beauty offers confidence, pleasure, and even moments of liberation but it also demands sacrifices, from silence to self-erasure.

Ultimately, what is at stake is not only how we look, but how we live. If beauty remains a gatekeeper to dignity, opportunity, and acceptance, then it must be interrogated. Who decides what is beautiful? Who is allowed to be seen, and who is made invisible? Who profits from our insecurities? And who pays the price for meeting standards that are always just out of reach?

In asking these questions, we begin to see that becoming beautiful is not a journey toward self-fulfilment it is a reflection of the world we inhabit. And perhaps true beauty lies not in the mirror, but in the courage to challenge the gaze that defines it.

(The author is an Assistant Professor at Chandigarh University, Mohali)

Trending Now

E-Paper