Dr Nisar Farhad

drnisarfarhadku@gmail.com

For me, motorcycling has never been merely about travel. Over the years, my journeys have evolved into written travelogues, documenting landscapes, culture, lived histories and a means to observe landscapes closely, engage with local cultures and document histories both lived and remembered. Continuing this engagement with travel and writing, a recent winter motorcycle journey from Pulwama to the twin sacred lakes of Mansar and Surinsar proved to be both enriching and reflective, revealing how geography, mythology and community belief intersect in the Jammu region.

Winter journeys have a character of their own. Roads are quieter, destinations less crowded and nature appears in a subdued yet honest form. On January 11, I started my ride from Pulwama at around 10 am. As I headed south, the biting cold of Kashmir slowly gave way to the comparatively milder winter of Jammu. The transition was not just climatic but cultural as well. Mountain roads gradually flattened into rolling hills, roadside shrines appeared with greater frequency, markets grew busier and sunlight felt warmer. After covering nearly 263 kilometres, I reached Mansar by evening and halted for the night at the Mansar Resort.

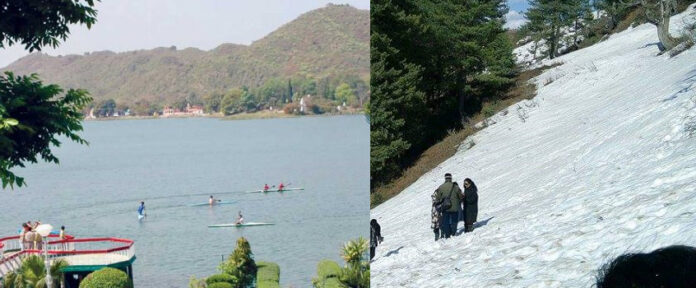

The following morning, January 12, Mansar Lake welcomed the day in a calm, almost meditative stillness. Located on the Samba–Udhampur Road, about 22 kilometres from Samba, Mansar is among the most prominent religious and recreational sites in the region. The lake is encircled by forested hills and a series of temples dedicated to various Hindu gods and goddesses. A prominent Nag (serpent) temple on its banks highlights the area’s long association with serpent worship, a tradition deeply embedded in local belief systems.

Mansar’s spiritual significance is closely tied to Mahabharata mythology. The lake is often associated with the sanctity of Lake Manasarovar. According to legend, after the Kurukshetra war, the Pandavas performed the Ashwamedh Yagna to establish their supremacy. The sacrificial horse was captured by Babruvahan, son of Arjuna and ruler of the region. In the ensuing battle, Babruvahan unknowingly killed his own father. Upon learning the truth, grief-stricken Babruvahan sought redemption and was told that Arjuna could be revived only with the Mani, a sacred gem possessed by Sheshnag, the divine serpent.

Legend narrates that Babruvahan pierced the earth with an arrow, creating an underground passage known as Surangsar, now called Surinsar. After defeating Sheshnag and obtaining the Mani, he emerged at the other end of the tunnel at Manisar, present-day Mansar. Springs later emerged at both ends of this passage, giving rise to the twin lakes of Mansar and Surinsar, spiritually binding them through myth and memory.

This mythological lineage continues to shape everyday practices around Mansar Lake. The lake supports several freshwater fish species, including rohu, catla, mrigal and common carp. Despite this abundance, fishing and consumption are traditionally prohibited. For local communities, the fish are sacred, associated with the Nag deity and feeding them is considered an act of devotion. Over generations, belief has quietly functioned as an effective form of ecological conservation, protecting the lake without the need for strict enforcement.

After spending nearly two hours walking around the lake, observing rituals and absorbing the tranquillity of the surroundings, I continued my journey towards Surinsar Lake. Located about 24 kilometres from Jammu city and roughly 9 kilometres from Mansar, Surinsar is the quieter and lesser-visited twin. Though smaller in size, it possesses a distinct charm. Surrounded by wooded slopes and open skies, the lake offers a serene atmosphere, particularly appealing to those seeking solitude away from crowded tourist spots.

Surinsar mirrors Mansar in both ecological composition and cultural restraint. The lake and its surroundings form part of the Surinsar–Mansar Wildlife Sanctuary, which is home to diverse fauna, including spotted deer, nilgai, sambhar and a variety of bird species. The area also holds religious significance, with devotees visiting to perform Mundan ceremonies and post-marriage pheras on the lake’s banks. In recent years, aarti is performed every Sunday evening, drawing local participation and reinforcing the lake’s spiritual importance.

Due to its proximity to Jammu city, Surinsar witnesses a substantial influx of visitors during weekends and holidays, particularly from Jammu. For many, it serves as a nearby retreat from urban life, especially since other popular destinations like Patnitop are comparatively farther away. However, the lack of adequate infrastructure and basic amenities often compels visitors to shorten their stay, highlighting the need for improved facilities to enhance the overall tourism experience. The lakes may be further developed through a balanced approach that protects their religious and ecological significance. The J&K Tourism Department may consider improving basic amenities such as clean toilets, regulated parking and organised vending areas using local design elements. Effective waste management, restrictions on single-use plastic during peak tourist months from March to October and installation of informative signboards can promote responsible tourism. Any recreational activities should remain limited and non-motorised. Involving local communities in guiding and maintenance along with the use of solar lighting and native plantation can enhance the visitor experience while preserving the natural and spiritual character of the lakes.

Owing to the winter season, visitor presence during my journey to twin lakes remained minimal. The lakes lay largely undisturbed, their surroundings marked by silence rather than crowds. Locals pointed out that the peak tourist season extends from March to October, when pleasant weather, blooming vegetation and improved accessibility draw significantly larger numbers of visitors. Winter, though less favourable for tourism, offers a clearer perspective on the natural and cultural character of the lakes, free from seasonal pressure.

From Surinsar, my journey continued towards Jammu city, where sacred landscapes gradually gave way to urban rhythms. Jammu reveals itself in layers. The Raghunath Temple complex, one of the largest temple clusters in North India, anchors the city’s spiritual identity, while bustling areas like Ranbir Market and Link Road reflect its commercial vibrancy. A visit to Bahu Fort offered panoramic views of the Tawi River flowing quietly below, while the adjoining Bagh-e-Bahu gardens provided a peaceful vantage point above the city. The Amar Mahal Palace, overlooking the river, stood gracefully against the winter sky, evoking memories of Jammu’s Dogra heritage.

I stayed overnight near Jewel Chowk and began my return journey on the morning of January 13, departing at 9:30 am and reaching home safely by evening.

This winter ride reaffirmed a simple yet profound truth: some landscapes endure not merely because they are protected but because they are believed in. At Mansar and Surinsar, mythology safeguards ecology, while in Jammu, history continues to coexist seamlessly with everyday life. On two wheels, across winter roads, the journey offered not just travel but perspective.

(The author is an educator currently serving as a Lecturer in Chemistry with the School Education Department in Jammu and Kashmir.)