Col Tej K Tikoo

Due to the persecution of Kashmiri Pandits at the hands of many Muslim rulers after the arrival of Islam in Kashmir in the fourteenth century, Kashmiri Pandits had witnessed six exoduses from Kashmir before India’s independence in 1947. By the time the last exodus of Hindus of Kashmir took place in 1989-1990, there were approximately half a million Pandits left in the Valley.

After India gained independence from Britain, Kashmiri Pandits could not be faulted for thinking that ‘exoduses’ were now a thing of the past. They assessed that being part of democratic, multi-ethnic, and secular India, was guarantee enough of their safety and security. Even after witnessing the large-scale violence perpetrated against them in Anantnag district and in some other areas of the valley in 1986, Kashmiri Pandits’ faith in the justice of Indian democracy did not waver. Alas! Such thinking proved to be only a fantasy.

A constant factor in Kashmir’s politics and social life has been Pakistan’s obsession with and its repeated overt and covert interventions in Kashmir.

In 1969, Jammu and Kashmir police unearthed a conspiracy to ignite religious and separatist passions in the valley when they arrested a number of students belonging to Al Fatah (named after the well-known Palestinian guerrilla group), from a house in Barsoo, located on the banks of River Jhelum at Letpora. Further investigations revealed that the group was the creation of Pakistan’s ISI, which had directed them to unify students for a struggle for Kashmir’s secession by targeting school, college, and university students to turn them into the mainstay of a proxy for Pakistan for future struggle.

During the decade of ‘Seventies’, many political developments at the national and international level impacted Kashmir’s internal politics adversely. A host of radical Islamic scholars in the garb of Maulvis and teachers of Madrassas from outside the state were employed to indoctrinate Kashmiri youth. Therefore, Islamic ideology became the driving force of the militant violence that broke out later in 1989.The ideological justification for their communal activities was provided by the Islam’s philosophy of Jihad. Separation of Jammu and Kashmir from India became its long-term objective and turning the valley into a Muslim theocratic state, became its immediate goal. This entailed creating religious fervor against the Kafir, who was well identified and readily available, next door.

By the middle of eighties Pakistan launched a virulent campaign against India, making use of every platform available to it. The fundamentalist Muslim organizations like the Tabhligi Jammat, the Jammat eIslami (JeI), Ahle Hadis and Salafists, carried outdoor-to-door campaigning to recruit new converts to their extremist ideology. The Mullahs used the mosque and its pulpit to preach hatred against India and the Kashmiri Pandits whose annihilation became their top priority. For radical Islamists, there could not be a more noble cause!

In the initial phase of insurgency, Pakistan made use of Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) and its student wing, the Jammu and Kashmir Students Liberation Front, to foment trouble in the valley. It was a well thought out and deliberate move as the Front’s slogan of ‘Azadi’ (Independence) touched a sympathetic chord among the general population and therefore, elicited greater acceptability and participation. It also enjoyed the advantage of having its cadres present in almost all mainstream political parties of Kashmir. Taking advantage of the simmering discontent among the people, the JKLF soon infiltrated every segment of Kashmiri society and the government apparatus, to subvert it from within.

However, according to ISI thinking, it was only the JeI, with its strong ideological moorings, who could be depended upon to provide a regular supply of committed foot soldiers to wage a long-term Jihad to achieve its objectives. Therefore, a secret meeting was arranged between Pakistan’s dictator, Zia ul Haque and Amir of JeI, Said-ud-Taribilli, in 1982. It was in this meeting that various nitty-gritties of the launch of forthcoming Jihad in Kashmir were thrashed out. Consequently, soon after this secret meeting, the first batch of JeI volunteers, which included the son of Ami rhimself, crossed over to Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK). They were trained there in Khalid-bin-Walid, Abu Jindal and Al Farooq camps. By the early 1980s, Jammat e Islami’s Al-Badr camp, under the command of Zamreen Khan, was specifically tasked to train JeI cadres. On their return they became the first foot-soldiers of new war unleashed by Pakistan in the Valley.

In the meantime, the political situation in the state was deteriorating very fast. The State assembly elections of 1987, largely believed to have been rigged by Congress-National Conference alliance, served as a catalyst for fanning the classical insurgency in late 1989. Mohamad Yousuf Shah, one of the victims of the blatant rigging, later metamorphosed into Syed Sallah-ud-din and fled to PoK, where he is presently heading the United Jihad Council created by Pakistan. His election agents formed the vanguard of JKLF. They were Hamid Sheikh, Ashfaq Wani, Javed Nalka and Yasin Malik. They were known by the acronym HAJY, formed by taking the first letter of their respective names.

When insurgency broke out in 1989-90, the radical Islamists held complete sway. Killings of prominent Kashmiri Pandits on the one hand, and targeting ordinary Pandits in unknown and far-flung areas on the other, created enormous fear, panic and overwhelming sense of insecurity in the minds of this minuscule minority. Through sustained campaign with the help of posters, hoardings and public address systems blaring out from pulpits of the mosques, Pandits were offered the same three choices that their forefathers had been offered centuries ago – ralive, galive ya tsalive. State machinery was totally subverted, paralyzing those instruments of the administration which could be used to prevent the killings of Pandits and instilling a sense of security among the beleaguered Hindu community.

Terrorist activity that began in earnest got an impetus during the next phase of increased violence, which started immediately thereafter. A number of school buildings were burnt and several business establishments had their go-downs looted and ransacked. Bars and wine shops were now made the target and were looted and bombed during day time. Prominent tourist hotels like the Broadway Hotel were asked to wind up their bars, while Amar Singh Club, Srinagar Club and Golf Course, which had the Chief Minister himself as their patron or president, had to close down their bars. Liquor traders were attacked, their premises looted and ransacked, forcing them to close their business. To showcase the reach and acceptability of their appeal, they would bring the administration and routine life to a standstill by imposing curfew, which they named as civil curfew. It was an extreme form of what is known as bandh or strike outside the valley. Sometimes, these curfews would last for days on end.

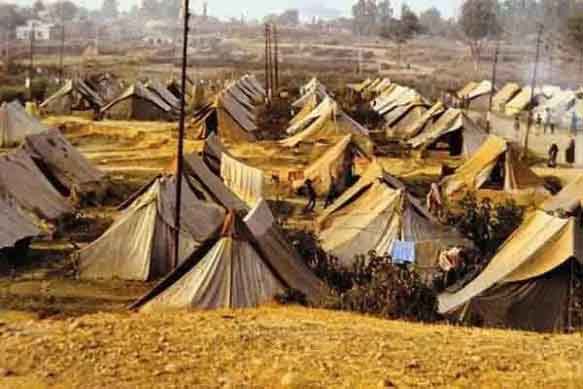

That the violent campaign will prove most harmful to the Muslims of Kashmir itself was lost sight of by the Kashmiris, who saw it as a panacea for all their imagined ills. To the microscopic minority of Kashmiri Pandits, it brought death and destruction. It ended up in their being uprooted from Kashmir; their home for as long as their history goes, only to be abandoned and forsaken as refugees by the powers that be.