Lalit Gupta

Basohli, which emerged in the mid-17th century as the new capital of the parent state of Billawar, rose to prominence not only as an urban settlement of eminence in the Jammu region but also as a centre of cultural and artistic excellence.

Despite operating under the partial political autonomy granted by the Mughal suzerainty, generations of local Pala rulers succeeded in transforming Basohli into a vibrant cultural hub. Here, India’s millennia-old civilizational values found renewed expression alongside contemporary artistic and spiritual traditions.

Deeply influenced by the principles of Vaishnavism and the Bhakti movement-along with the concurrent worship of Shiva (Shaivism) and the Divine Mother (Shakti)-Basohli evolved over the last three centuries into a prominent centre of dharma and Indian Knowledge Systems. These included Sanskrit literature, astrology, Ayurveda, fine arts, and classical literature. The region witnessed the harmonious confluence of local traditions with pan-Indian civilizational values, making it a beacon of cultural syncretism in the hills.

Foundation of Modern Basohli: Originally known as Vishwastahli, Basohli was founded as the new capital by Raja Bhupat Pal in 1635 CE. Seeking to establish a strategically secure and symbolically powerful centre of rule, Raja Bhupat Pal shifted the capital from Billawar to a new location on the banks of the River Ravi. According to historian Kahn Singh Billowia, a native of Basohli, the Raja made this move to fortify the capital against threats from rival hill states, such as Chamba and Nurpur. The relocation marked the formal foundation of modern-day Basohli.

Political Context and Mughal Influence: Despite fluctuating relations among the various principalities of Jammu and Himachal, the entire hilly region ultimately came under the influence of the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire. According to historical sources, in 1419 CE, Sultan Mubarak Shah of Delhi entrusted the governance of the hill tracts to 22 regional chieftains, known as Pattedaras, among whom the rulers of Basohli were included.

By the end of the 16th century, Basohli came directly under Mughal control when the Mughal army defeated Raja Krishan Pal in 1590 CE. From that point onward, Basohli’s rulers regularly attended the Mughal court, maintaining diplomatic and cultural ties with the imperial centre while continuing to nurture regional traditions.

Geographical Significance and Strategic Location: Situated on the right bank of the River Ravi, Basohli gained significance as a vital emporium and trade centre. Its strategic location enabled it to serve as a nexus for trade routes connecting the Indian mainland with Kashmir and Central Asia, via neighbouring regions such as Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. Basohli enjoyed prominence among its neighbouring principalities: Bhaderwah to the north, Chamba and Nurpur to the east, Ramnagar (Bandralta) to the west, Lakhanpur and Jasrota to the south, Ramkot (Mankot) to the west, and Jasrota to the southwest. These connections bolstered its political importance and economic vitality.

Urban Form and Cultural Landscape of Basohli: Established during the era of Muslim rule, Basohli’s urban landscape was characterised by sprawling monument complexes surrounded by organically evolved residential neighbourhoods, or mohallas, based on principles of Vastu Shashtra. Founded by Raja Bhupat Pal, Basohli’s iconic fort-cum-palaces underwent periodic additions and embellishments under his successors-Sangram Pal, Kirpal Pal, Dheeraj Pal, Medini Pal, and Amrit Pal. Notably, the Rang Mahal and Sheesh Mahal were adorned with exquisite mural paintings under the patronage of Raja Mahendra Pal.

The French traveller Vigne, who visited Basohli between 1835 and 1839, was so captivated by the Sheesh Mahal that he described it as the finest building he had seen in the East. He praised its square turrets, embattled parapets, Chinese-style balconies, and a moat-like tank in front. He even likened its grandeur to that of Heidelberg Castle, highlighting the sophistication of Basohli’s architectural aesthetics. In its prime, Basohli was a remarkable synthesis of military strategy, cultural refinement, and artistic innovation.

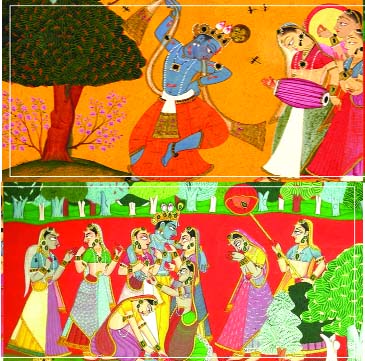

Basohli School of Pahari Painting: A Cultural Zenith: The true jewel in Basohli’s cultural crown is the Basohli school of Pahari painting, which propelled the town to international artistic fame. Known for its strong outlines, vivid folk-inspired colours, and robust figures, Basohli kalam is often hailed as the mother of Pahari painting schools. Rooted in the pre-Mughal continuum of Bhartiya Chitrakala, this school played a foundational role in nurturing the later flourishing of Kangra, Guler, Chamba, and Nurpur schools. Flourishing in the 17th century, the Basohli miniature style marked the climax of a 2,000-year-old Indian painting tradition, carving a unique and lasting identity for Basohli in the sub-continental artistic legacy.

Shri Neelkanth Maharaja: Shared Legacy of Kishtwar and Basohli:

Neelkantha Mahadev Shivalaya, Basohli: Located near the royal palaces of Basohli, the Neelkantha Mahadev Shivalaya is significant both architecturally and mythologically. This east-facing temple features a garbha griha (sanctum sanctorum), a circumambulatory path, and a towering shikhara, all elevated on a jagti (raised platform) accessed by a flight of steps.

The Mahabharata Legend: The temple’s origin is steeped in a fascinating legend drawn from the Mahabharata. During the epic war, Arjuna severed the arm of Raja Bhurishrava, which bore a jewel resembling a Shivalinga. An eagle attempted to carry the arm but dropped it into a well.

This eagle was later reborn as a girl in Kishtwar. One day, while fetching water, she laughed upon seeing an eagle drop a snake. When questioned by the Raja of Kishtwar, she recounted her past life. Moved by the story, the Raja retrieved the Shivalinga-shaped stone from Kurukshetra. The Shivalinga became an object of reverence, reputed to reveal devotees’ past lives. However, when a curious queen saw herself as a she-monkey, she threw the Shivalinga into a fire, turning its colour from blue to blue-black. This act is said to have triggered a devastating drought in Kishtwar.

Temple Construction by Raja Bhupat Pal: Raja Bhupat Pal of Basohli, upon receiving a divine message in a dream, invaded Kishtwar, married a local princess, and brought the Shivalinga to Basohli. There, he constructed the Neelkantha Mahadev Temple, named after the now blue-black hue of the sacred stone. More than a place of worship, the temple symbolises the intertwined cultural and spiritual legacies of Kishtwar and Basohli. It remains a powerful testament to the region’s deep mythology, architectural excellence, and enduring devotion.

Other historic temples in and around Basohli include Mahadera (Trilokinath) Temple, Chounchalo Devi Mandir, Jatajuta Mandir, Mahakali Mandir, Chamunda Mandir, Sheetla Mata Mandir, Kaali Mandir, Hatta and Chamund Mata Zheel Waali.

After the last King of the Pal Dynasty, Raja Kalyan Pal, was dethroned in 1836 AD, and the State was transferred as ‘Jagir’ to Raja Hira Singh, the nephew of Raja Dhiyan Singh, Basohli fell into disarray.

After Post-1947, Basohli’s monumental and artistic heritage was reduced to ruins by the apathetic attitude of the so-called popular governments. Today, only a turret and a heap of fallen walls of the once magnificent Palace remain as mute witnesses to the glorious past of Basohli.

Trending Now

E-Paper