The flag-off of the Katra-to-Srinagar Vande Bharat Express did far more than add another blue-and-white rake to the Indian Railways timetable. It consummated a 127-year-old dream first sketched by Dogra Maharaja Pratap Singh in 1898 and, in the same stroke, sent an unmistakable signal that steel, tunnels and human resolve will always outlast shells and ideology. British surveys under the Maharajas between 1898 and 1909 all declared the Himalayas “impassable” without technology that did not yet exist. Colonial priorities shifted, partition intervened and multiple wars froze the blueprint. Only in independent India’s third decade did the idea re-emerge, and even then progress was halting-until political will finally converged with 21st-century engineering. Thus the Udhampur-Srinagar-Baramulla Rail Link became a genuine national priority, and the project began receiving yearly reviews from the Prime Minister’s Office.

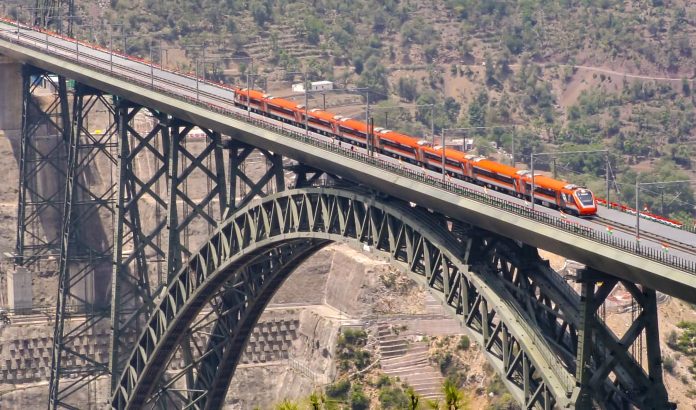

The raw statistics stagger. The 272-km corridor pierces the Pir Panjal with 36 tunnels totalling 119 km and 943 bridges that hopscotch deep gorges and slide across landslip-prone shelves. The showpiece is the Chenab Arch Bridge: 1315m long, an arch span stitched together by cable cranes swinging 30,000 tonnes of steel 359m above the river-29m taller than the Eiffel Tower-and designed to shrug off winds of 260 km/h and Zone V earthquakes. Five kilometres downstream the Anji Khad Bridge, India’s first cable-stayed rail link with 96 fan-like cables, anchors its asymmetrical pylon into the fractured Shivalik schist-a geometry textbook written in steel. Much of the steel travelled hundreds of km with the nearest railhead stopped at Udhampur; half of it then rode mule caravans where gradients topped 70 percent. Custom wind-tunnel testing facilities were erected on site to model vortex shedding; blast-resistant concrete was poured to protect the deck from the region’s volatile security climate.

These marvels demanded not just rupees but lives as well. Terror outfits repeatedly tried to halt work; the most searing memory is of 30-year-old IRCON engineer abduction at an Awantipora work front in June 2004 and found with his throat slit two days later-an attack that briefly forced the PSU to withdraw its entire cadre from the Valley. Scores of anonymous labourers succumbed to rockfalls, hypothermia and Covid-19. Yet, the workforce-25 per percent of it recruited locally-returned season after season, folding prayer flags into hard-hat liners and trusting the geology reports. Their perseverance is etched into every portal.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to inspect the arch on foot, Tricolour in hand, was not mere optics. Since 2019 the USBRL status note has figured in every Pragati review, and bureaucrats recount midnight conference calls after each cost or geological escalation. PM coupled the inauguration with a Rs 46000-crore development package, underscoring that transport corridors unlock wider opportunities.

For travellers, the payoff is immediate. The Katra-Srinagar Vande Bharat now covers the journey in a few hours; a standard chair-car seat costs peanuts, little more than an intercity bus and a fraction of peak winter airfares that often breach Rs 8 000. The train skims past the Chenab arch before vanishing into the 13-km T-50 tunnel and bursting into the Valley-a panorama that tour operators are already marketing as “India’s Glacier Express”. No airline window can match a vestibule where every five minutes the scene toggles from pine carpets to snow corries, orchestrated by head-end telemetry rather than jet altitude. The arch’s visitor gallery and the Anji pylon’s glass elevator, due to open later this year, will anchor a new niche of railway heritage tourism in the Jammu division, diverting Vaishno Devi pilgrims for an extra day’s stay. Nine million Mata Vaishno Devi yatris each year represent a convertible market for Kashmir houseboats, ski slopes and saffron fields-now just one seamless ticket away. Even an incremental 5% diversion would inject an extra Rs 500 crore into the Valley’s service sector annually.

Logistics gains will be transformative. Horticulture currently loses 15-20 percent of apple tonnage each year due to NH-44 closures. A single 45-wagon perishables rake can move 1600 tons of fruit overnight to Azadpur Mandi, shaving freight bills by half and eliminating the spoilage margin. Conversely, fertilisers, cement and LPG can flow in at predictable tariffs, flattening the price spikes that historically fed Valley resentment. Modular factories along the Sangaldan and Qazigund freight hubs can now adopt just-in-time supply chains, something impossible when every truck crossing Banihal cratered the scheduling. Cheaper steel inbound means cheaper prefab greenhouses; cheaper outbound freight means willow bats can chase world markets rather than truck depots. Symbolically, the train dissolves distance in minds. Last year over 18 million Indians rode Vande Bharats; now every one of them can-literally-extend that habit to Kashmir. When classrooms in Chennai or Chandigarh plan study tours to Srinagar by rail, the Valley’s isolation narrative loses steam. That is people-to-people interaction at 110 km/h.

From a defence standpoint, the USBRL offers the Northern Command a weather-proof artery for men and materiel, reducing dependence on the vulnerable NH-44. Each Vande Bharat rake can be converted into a casualty-evacuation train within hours-a life-saver in a region that hosts the world’s highest troop density.

Critics will count the pending tasks: extending the line to Kupwara, building dedicated freight loops, and safeguarding fragile slopes from unregulated tourism. Yet the essential verdict is in. By defeating gradient, blizzard, bureaucracy and gunfire, Indian Railways has set a benchmark in project delivery under adversity. The arch above the Chenab is therefore more than an engineering curve; it is a social arc bending from mistrust to mobility. It remembers sacrifices and honours the anonymous navvies who drilled through rock and fear alike. It vindicates the Dogra Maharaja’s notebook sketch and validates a PM’s insistence that the last mile of integration be travelled on steel wheels. When the inaugural train thundered over the river, schoolchildren aboard chanted “Jai Mata Di.” This time the echo replied, via rail horn, that Jammu & Kashmir’s future will be written not in casualty counts but in timetables-on a line that proves the wheels of development can and will outrun the blasts of hate.

Trending Now

E-Paper