India’s Long Walk on a Diplomatic Tightrope

B S Dara

Seventy years in diplomacy is more than a measure of time. It is a long season in which loyalties are weighed, suspicions resurface, and accumulated decisions gradually harden into enduring strategic habits. India’s dealings with the major powers have rarely followed a straight or predictable path. They have shifted with circumstance, pressure, and opportunity. Yet through decades of uncertainty and adjustment, one conclusion has steadily emerged. India’s endurance in global politics has rested less on emphatic declarations of alignment and more on the careful and restrained management of balance.

India’s relationship with Russia, first as the Soviet Union and later as the Russian Federation, belongs to a category of ties shaped by sustained strategic necessity rather than fleeting convergence. By contrast, India’s engagement with the United States, particularly since the end of the Cold War, has carried great promise while remaining vulnerable to changes in Washington’s domestic political climate. The years under a Trump-led administration exposed these limits with unusual clarity.

To understand India’s present position, standing between Russia, an uncertain West, and an increasingly assertive China, it is necessary to look backward before looking ahead. The origins of the Moscow equation explain much of India’s current strategic caution. India–Russia relations took shape at a moment when India was searching for space to think independently. During the 1950s and 1960s, many Western capitals viewed India through the rigid framework of Cold War binaries. The Soviet Union, by contrast, offered political room without demanding an ideological alignment, and without insisting on military alliances. That space mattered.

Over time, Moscow demonstrated consistency when consistency carried weight. In 1971, during the Bangladesh Liberation War, when the United States openly tilted toward Pakistan and deployed the USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal, it was the Soviet Union that extended decisive diplomatic support. Its veto at the United Nations Security Council, reinforced by the Indo Soviet Treaty of Peace Friendship and Cooperation, shaped the strategic outcome of the conflict. For India, the importance of that moment has never faded.

This episode remains central to how Indian policymakers perceive Russia, who in the past, has not only been an abstract partner but the one that acted when the stakes were highest. Defence cooperation followed naturally as a practical extension of trust. Aircraft, armoured platforms, missile systems, submarines, and later joint development projects came to form the backbone of India’s military capabilities for decades. Equally important was the manner of cooperation. Moscow’s approach differed sharply from that of Western suppliers. Political conditions were minimal, technology transfer was deeper, and supply lines remained largely intact even during periods of diplomatic stress.

Economic cooperation matured more gradually but left a lasting imprint. Soviet era steel plants at Bhilai and Bokaro, energy collaboration in Sakhalin, and nuclear cooperation at Kudankulam reflected long-term commitments rather than transactional arrangements. Russia viewed India less as a market and more as a strategic partner in development. This legacy continues to shape Indian strategic thinking. In global affairs, strategic memory is seldom erased by short-term change.

India’s engagement with the United States gathered momentum only in the late 1990s and early years of the new century. The 2005 Civil Nuclear Agreement marked a defining diplomatic breakthrough. It acknowledged India’s nuclear status without forcing formal adherence to the Non Proliferation Treaty and signaled strategic trust after decades of sanctions and restraint.

The years that followed saw expanding defence cooperation, rising trade flows, growing technology exchanges, and deepening people to people ties. The Indo Pacific idea appeared to offer strategic convergence without the binding obligations of formal alliance commitments. For many in New Delhi, the relationship seemed poised to move beyond its traditionally cautious phase. External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, in his writings on India’s engagement with the United States, has consistently emphasized sobriety over sentiment. His assessment is clear and pragmatic. India and the United States identify overlapping interests and negotiate accordingly. Progress must therefore be incremental and carefully managed.

That realism faced its sharpest test during the Trump administration.

The Trump presidency brought volatility into relationships that rely on predictability. Tariffs displaced trust. India lost its Generalized System of Preferences trade benefits. Visa regimes tightened even as strategic rhetoric intensified. Public diplomacy became overtly transactional and at times dismissive. More damaging than any single measure was the erosion of confidence.

Despite frequent references to partnership, Washington continued to hyphenate India with Pakistan when convenient. At the same time, Islamabad was re engaged under the framework of Afghanistan logistics and regional mediation. For New Delhi, this was not entirely new but it was clarifying. India’s attempt to elevate ties with the United States encountered the structural reality that American foreign policy, particularly under populist leadership, remains prone to abrupt reversals.

Diplomacy for India cannot operate at the tempo of electoral cycles elsewhere. As Washington struggled to maintain consistency, Moscow and Beijing adjusted their strategic calculations. Russia, constrained by Western sanctions and sustained pressure, turned decisively toward Asia. China, already India’s principal strategic challenger, accelerated efforts to reshape global financial and institutional frameworks. Within this setting, BRICS emerged as both opportunity and concern.

India’s participation has been deliberate and restrained. Institutions such as the New Development Bank offer pragmatic diversification, yet New Delhi remains wary of arrangements that appear overtly anti Western or heavily skewed toward Chinese dominance. This caution has frustrated both partners. Russia sees India as a stabilizing presence within BRICS. China often expects alignment rather than coordination. India has resisted both expectations.

The Ukraine conflict further intensified India’s balancing challenge. Faced with rising global energy costs, New Delhi increased purchases of discounted Russian crude. The decision was commercial in nature and driven by domestic economic considerations. Washington’s response, articulated publicly in moral language, carried clear strategic intent. Pressure followed. India gradually diversified its energy basket and reduced Russian imports under visible Western scrutiny.

President Vladimir Putin’s subsequent engagement with India must be read in this context. Moscow’s outreach reflects an expectation that partnerships must demonstrate resilience under strain rather than convenience. Energy cooperation through long term LNG contracts, upstream investments, and nuclear collaboration remains the most immediate area of shared interest. Defence co production, fertilizers, space cooperation, and critical minerals offer additional scope for recalibration. This outreach is pragmatic rather than sentimental.

For India, Washington’s renewed engagement with Pakistan remains a persistent concern. History suggests such relationships rarely remain limited. Once activated, military assistance, intelligence coordination, and diplomatic legitimacy tend to expand. This reality reinforces India’s reluctance to formalize alliance commitments. Strategic autonomy in this sense is not rhetorical. It is protective.

India thus finds itself once again at the intersection of competing power centres, by geography and circumstance. New Delhi’s strategy is likely to remain layered. It will seek to maintain core ties with Russia while limiting dependence. It will engage the United States where interests converge and resist pressure where they do not. It will participate in BRICS without ideological alignment. It will manage China independently. And it will attempt to insulate South Asia from becoming collateral in broader rivalries.

Will this approach succeed. There are no guarantees. Strategic autonomy demands constant calibration, patience, and an ability to absorb pressure from multiple directions. Yet history offers guidance. India’s foreign policy has endured because it refused illusions. Russia offered reliability in moments of crisis. The United States offered opportunity alongside unpredictability. China offers scale accompanied by caution. India’s responsibility ultimately lies in coherence.

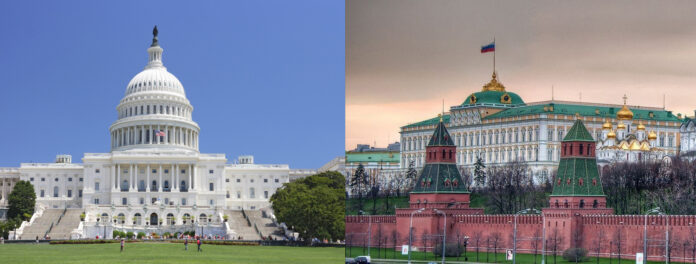

The long walk between Moscow and Washington is therefore more about maintaining equilibrium along the way. In an era of rapid change and persistent uncertainty, that capacity to remain balanced while the ground shifts beneath may prove India’s most valuable strategic asset.

As an independent foreign affairs observer, I see that India’s approach may deliver limited short-term gains, but it has preserved long-term flexibility. In a shifting global environment, that flexibility remains essential.

This poetic lament by Faiz Ahmed Faiz aligns well with the current diplomatic situation in a straightforward way. For India, it reflects the need to manage international relationships beyond sentiment, focusing instead on practical outcomes and national interest.

“Aur bhi dukh hain zamane mein mohabbat ke siwa,

Rahatein aur bhi hain wasl ki rahat ke siwa.”