Tarun Chugh

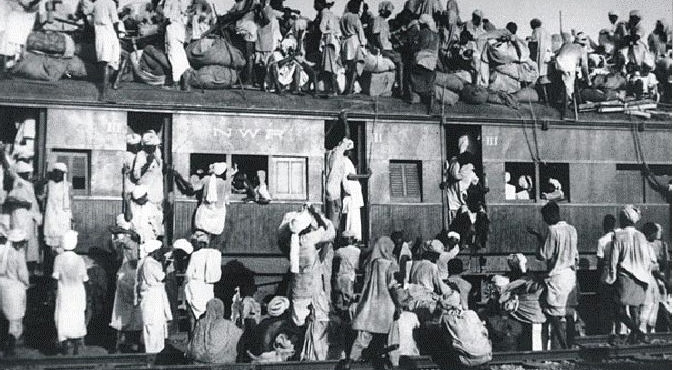

In the torrid August of 1947, India found itself ablaze-literally and figuratively. On what should have been a dawn of freedom, villages on both sides of the new border burned in the twilight. Caravans of broken families trailed off into the horizon; weary men, women and children trudged along dusty roads under a blood-red sky, leaving behind everything except the memories carried in their hearts. Train after train crammed with refugees chugged out of stations like Lahore and Amritsar-some never reaching their destinations. In the eerie silence after each train’s departure, only the ghosts of cries and the crackling of distant fires remained. This was Partition in India: a tableau of chaos, violence, and human upheaval on a scale the world had never witnessed before. It was a moment of independence intertwined with unspeakable trauma, a moment our nation must remember not to reopen old wounds, but to heal and learn from them.

Punjab and Bengal bore the brunt of Partition’s horrors. Geography made it so: the Radcliffe Line carved right through the heart of Punjab and Bengal, slicing through farms and rivers, bisecting railway lines and Grand Trunk roads, and cleaving an ancient community into two. The province’s rich tapestry of faiths-Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims woven together over centuries-was torn abruptly. This land became the epicentre of the great exodus. Millions of Hindus and Sikhs fled west Punjab and East Bengal for India. Every arterial road and rail route in Punjab and Bengal swelled with human convoys heading in opposite directions, desperate and afraid. The administrative systems collapsed under this tidal wave of humanity. Law and order, already brittle as the British rushed to exit, broke down entirely. A British study later admitted the colonial authorities were “surprisingly unprepared” for the cataclysm that unfolded; the nascent governments of India and Pakistan were overwhelmed as well. Where the Partition line cut through densely populated districts, the result was anarchy: neighbors who had lived peacefully for generations now found themselves on opposite sides of a deadly divide, with virtually no security forces able to contain the spiraling violence.

Partition Horrors Remembrance Day

The carnage in Punjab was unprecedented. Towns like Rawalpindi, Lahore, Amritsar and Sheikhupura saw massacres, arson and brutal retaliatory killings in an infernal cycle. Trains that should have been symbols of modernity became instruments of horror: many arrived at their destinations laden only with bloodied corpses, earning the name “blood trains” or “ghost trains”. One survivor remembered seeing a train pull into Delhi “heaped with…dead bodies,” blood dripping from the carriage-a sight that extinguished any last hope of returning home. Mobs set upon caravans of refugees on foot; entire villages were razed overnight. The violence spared no one. An estimated 75,000 women were raped or abducted amid the communal hatred, a grotesque crime often compounded by mutilation and enslavement. Children were murdered before their parents’ eyes; infants were wrenched from mothers. Such was the madness that some witnesses, hardened by the recent World War, likened Partition’s brutality to a genocide, a hellscape on par with Europe’s darkest hours. By the time the slaughter subsided in 1948, more than 15 million people had been uprooted, and estimates of the dead range from 200,000 to 2 million souls. Most scholars settle on roughly one million killed, though new research from Harvard suggests the toll could exceed 2 million. The 1947 Partition stands as the largest mass refugee crisis of the 20th century, with around 14-18 million people displaced in a matter of months – fully 1% of humanity at that time uprooted from their ancestral homes. These numbers are not mere statistics; they are the testament of an unparalleled human tragedy centered on India’s soil. Sacrifice was unique in its scale and completeness: an entire way of life was destroyed almost overnight.

Yet amid this devastation, ordinary Indians carried extraordinary memories. What does one take when forced to flee home forever? Some snatched family ledgers or photographs; others grabbed soil from their courtyards, a fistful of memory. Many took keys – the physical keys to homes they left behind – tucking them tightly into waistbands or knotting them into the edges of their dupattas. In countless tales passed down, grandmothers recall how, in the frenzy of August 1947, they locked their doors and cupboards and carried the keys across the border, firmly believing they’d return someday. In another recollection, a woman from Lahore remembers departing families entrusting her family with bundles of house keys, as some neighbors still hoped the turmoil would blow over. Each key was a mute witness to a life interrupted. Each represented a house now occupied by strangers or reduced to rubble, yet still alive in someone’s mind. Even today, in cities like Amritsar, Jalandhar or Delhi, if you meet elderly Punjabi refugees – our nanis and dadis – they might show you an old, rusted key tied in a simple cloth. Eyes brimming with tears and pride, they pass these keys on to their children and grandchildren as sacred relics of a lost world. These keys unlock no doors today, but they unlock histories and emotions. They symbolize loss and longing, but also resilience and hope – the hope that kept an exiled people alive, and the resilience that fueled them to rebuild in a new land.

The memory of Partition lives on powerfully in India’s collective conscience. Families who lost everything did not simply “move on” – they rebuilt, yes, but they also remembered. They kept alive the name of the village or city left behind – in folk songs, in bedtime stories, in the dishes they cooked and the prayers they uttered. How could they forget? A mother who saw her child killed before her eyes could never forget. A grandfather who arrived in Amritsar in 1947 on one of the “ghost trains,” the only one of his family left alive, could never forget. Those who survived bore witness to both human depravity and human fortitude: they saw strangers from the other community commit atrocities, and also saw strangers who heroically saved lives. Indeed, amid the savagery were countless acts of courage and compassion – Muslim neighbours sheltering Hindu friends, Sikh farmers saving Muslim villagers from rioters, ordinary Hindus sharing their last roti with a starving refugee. The worst of humanity was met by the best of humanity. It is this complex legacy – of agonizing horror and abiding fraternity – that we as a nation must internalize. Partition teaches us that peace between communities is precious and fragile, and that once the fabric of trust is torn, the resulting bloodshed spares no one. The pain of Partition, Land of Gurus and Gods being splintered by man-made lines, left a deep scar on the soul of India. That scar is a warning: we must never allow such hatred to infect our people again.

While Punjab became the flashpoint in the west, Bengal bled in the east. The Radcliffe Line’s eastern cut severed Bengal into two – West Bengal in India and East Bengal, soon to be East Pakistan. Like Punjab, Bengal’s division was abrupt, ill-prepared, and brutally enforced. The bustling city of Calcutta turned into a reception centre for hundreds of thousands of Hindu refugees fleeing communal riots and targeted killings in East Bengal’s towns and villages. In Noakhali and Tippera, entire Hindu settlements were attacked in the months preceding Independence, forcing a mass flight to safety. The rivers of Bengal, which had for centuries been lifelines of trade and culture, now became routes of desperate escape. Families crowded onto ferries and bullock carts, carrying whatever they could salvage, many losing relatives to mob violence or the treacherous crossings.

The tragedy in Bengal carried its own unique anguish. In the east, the violence often came in sudden bursts, intertwined with long months of fear and deprivation. The communal riots of 1946 in Calcutta and Noakhali had already torn at the social fabric, leaving deep mistrust. By 1947, that mistrust exploded into a massive exodus. More than 3 million Hindus crossed from East Bengal into India over the next few years, their arrival straining West Bengal’s cities and villages to breaking point. Refugee camps sprouted on the outskirts of Calcutta, Howrah, and Siliguri, often with appalling sanitary conditions and little food. Like their Punjabi counterparts, Bengali survivors carried more than just physical scars – they brought memories of lost homes, desecrated temples, and ancestral lands now beyond reach. The suffering of Bengal stands as a reminder that Partition was not one tragedy but two, playing out at opposite ends of the subcontinent, united in their human cost.

It is in acknowledgment of this enduring pain that Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2021 declared August 14 to be observed every year as Partition Horrors Remembrance Day. This decision – coming after seven decades of independent India – is more than a symbolic gesture. It is an act of historic truth-telling and homage. For too long, the stories of 1947’s survivors lived only in personal memories and faded letters. Now, by officially dedicating a day to remember Partition’s victims, we have made those stories part of our national narrative. Prime Minister Narendra Modi struck the right chord when he said “Partition’s pains can never be forgotten. Millions of our sisters and brothers were displaced and many lost their lives due to mindless hate and violence.” He urged that this day “keep reminding us of the need to remove the poison of social divisions, disharmony and further strengthen the spirit of oneness”. In doing so, he gave voice to what every right-thinking Indian knows in his or her heart: that our unity is hard-won and sacred, purchased with the blood of those who perished in 1947. Observing Partition Horrors Remembrance Day nationally is India’s promise to its past – that we will remember the suffering of our people with dignity, and honor the sacrifice of those who did not live to see the tricolor fly. It is also India’s promise to its future – that we will teach each new generation about the devastation that communal hatred can unleash, so that such poison never spreads in our country again.

For the Bharatiya Janata Party, and for me personally, this commitment is profoundly important. The BJP has always stood for the idea of “Ek Bharat, Shreshtha Bharat” – One India, Great India – where our nation’s unity in diversity is celebrated and protected. Partition Horrors Remembrance Day is a part of that commitment: it ensures we do not whitewash the past or ignore its lessons. As a son of Punjab and as a proud Indian, I have heard the Partition stories at my own dinner table since childhood – tales told in choked voices by elders who lived that nightmare. I feel a deep sense of duty to those martyrs and survivors. We in the BJP will make sure that their sacrifices are never forgotten or in vain. By remembering the horrors of Partition, we also strengthen our resolve to thwart the divisive forces that ever seek to weaken India from within. Whether it is communalism, casteism, or any ideology of hate – we must reject it with all our might, for we know the catastrophe it can breed. Today, under the leadership of Prime Minister Modi, India is acknowledging its history – the glory and the pain – with open eyes. This honest reckoning makes us stronger. It cements our unity, because a nation that remembers its worst sorrow will guard its present unity even more fiercely.

It’s been nearly seventy-eight years since Partition. The world has changed, India has risen to new heights, and many of those who witnessed that terrible time are no longer with us. Yet, we still owe them a debt – to tell their story, to learn from their pain. We do not recount this chapter to rekindle bitterness – far from it. We tell it so we can salute their resilience and determination, and remind ourselves never to let such division take root in our nation again.

On this Partition Horrors Remembrance Day, as people across the country light candles and sound sirens in tribute, one image comes to my mind: an elderly woman in Amritsar quietly opening her chest of memories. Between old clothes and brass utensils lies the iron key to the house she left behind in 1947. Her hands tremble as she picks it up. The key is rusted, cold to the touch, yet for her, it is more precious than gold. It holds a story of both pain and pride: pain for the world she lost, pride that amid such adversity she never abandoned her dignity, her family, or her hope.

That woman survived the tragedy of 1947 and vowed her children would never face the same suffering. Today, that key is both a warning and a torch. A warning that when the demon of hatred takes over, it takes no time for homes to burn and nations to splinter. And a torch in the sense that the light of memory and unity will guide us through the dark roads of the future – the conviction that together we can ensure that the storm of enmity which once forced millions to lock their doors and leave forever will never rise again.

The keys of our past warn us that India’s future must never bear such wounds again. They stand as symbols of the country we must build, one where no one is forced to bid a final farewell to their home and soil. And that is the true lesson of these keys: that “Ek Bharat, Shreshtha Bharat” is not just a slogan but the victory mantra of unity, the national creed, our very foundation. The darkness of hatred can only be fought with the light of love and unbreakable unity, and we must hold on to that light, always.

(The author is National General Secretary of the BJP)