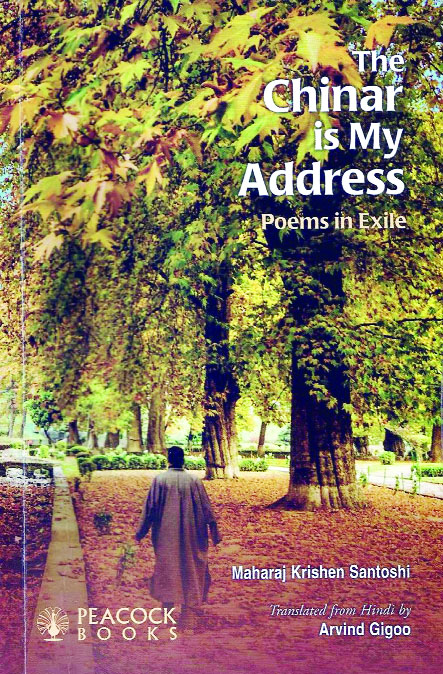

Adarsh Ajit

Though exile is the only theme of Santoshi’s The Chinar is My Address but he has intellectually dragged out the theme, titles and subtitles far from the shallow wells to the universal touches, both in emotions and in content. He has expanded ‘exile’ to political, social, historical and economical levels. He is bold and ruthless and scans the realities through his imaginative competence. Santoshi equates Pakistan with monsoons that thunder sometimes and burst lightings, and soon vanish. Monsoons also represent the vacillation, untrustworthiness and unpredictability of Pakistan. Ironically the poet tries to forget the history unsuccessfully when a daughter asks her father:

Papa /have you been to Pakistan? / Do monsoons/ become/Muslims there?

Santoshi recreates Jinnah’s Crescent that opens the gashes of history and the stark reality of the creation of Pakistan. Jinnah’s typewriter, his cap, the moon and his ambitions are dimensionally woven to divulge the chronological ugliness. The murderers of their consciences slay their enemy without assigning any rationale but feel proud to offer the prey a compliment in shape of a mirror so that the dead can explore the cause of his being killed.

‘as a tribute to your taste / we will/ keep a mirror in your coffin’.

The poet redefines exodus in totality, without naming anybody, or assigning it to any place. He calls himself a sign, a number and not a word. He has painted the sorrowful draught of exiled life in different colours and has symbolised the victims of terrorism with the sparrows who never give a challenge for a fight but are committed to sing. Nobody listens to them in spite of their apprehension of tumbling their nests. Santoshi has proved to be resourcefully gifted with using imagery of high calibre. Referring to the historical visit of Pt Kripa Ram and crafting it with poetry he converts the distances of ages into a ladder. He hides burnt skin but watches ancestress carrying the slain heads. He salutes the struggle of survival of his ancestors but finds himself entangled in the most tragic historical turn of the modern history. Twenty-five years of exiled life has delinked the exile from its roots. Even suspecting the milepost which gives the distance, the poet enquires from passerby if the road leads to Srinagar. The places inherited by him are now unknown to him. Now he has to resurface the warmth of his suppressed breath. The book ends with the poem Wooden Swords which also divulge the figure of a terrorised exile:

‘We are wooden swords/Even matchstick / frightens / us…..We are wooden swords/ Fire apart/ even a small knife/frightens/us….’

The poem Potter is the reflective and nostalgic outflow of both the displaced people and the people across the tunnel who were bonded together with socio-cultural and more importantly with the financial networks. In his dream Santoshi sees the tears of a potter whose pots are unsold because of exile but at the same time the potter brings the aroma of the poet’s land of birth in his earthen lamps.

‘I bought a lamp/from/the potter/put it/on fresh wound of my being’.

Though every wave is a perpetrator in erasing even the signs of the exiled lot but the community is resolute to survive whatsoever tools the enemies of survival and the masters of ethnic cleansing take in hands. The poet portrays the community as fearless. Unafraid of scorpions and the snakes the exiles write poetry, shout laughs and listen to the songs undauntedly. He challenges:

‘I am not a figure/drawn by a child/on a slate/How can you/ wipe me off?’

The poet thinks that the idols have captivated and subdued his existence and do not allow him to evolve on his own strength. In a pun Santoshi symbolizes God with a tailor who sews the skin but satirizes Him by quoting those children who roam naked and to the surprise he does not blame God for it. . But he alleges that gods are neither with us and nor for us. Despite installing their replicas in alien land the gods are criminally silent.

Satirically commenting on the socio-religious authorities, M K Santosh says that we are informed about those things which are realistically nowhere. The children are told how to cross Vaitarni when their realistic approach of life eludes the mechanics of life. Though the inheritance is to explore the myths but the irony is that even big brains are no way known to the way, not to speak of passing it. The poet sarcastically questions the preachers of legacy what will they convey to the offspring in a situation where muck flows in the brook and they have nothing at their back to offer:

‘The sunshine/will/feel shy/to descend/from/the sun’

The dumb/recite/poems to the deaf, The quiver/on the revenue stamp/asks me/are you happy over being alive? , I saw prophets impotent, Old man is taught to walk only up to polling booth, Till then let us scratch this hard ice to prove of being alive are the representative verses bisecting shallowness of the audience, inefficiency of the interpreters, the learned and the guides, the extreme callousness of the establishment, the inability of the seers and the selfish blackmail of even the old.

Santoshi has artfully used a reputed and often quoted Vaakh of Lallishwari. The poet has the record of burnt cotton and he is helpless to go home with the yarn which is not enough to pull the boat with.

Exile intensely terrifies the poet but when he falls in love with a woman, the response is similar. For him beauty and gun are the two faces of the same coin and both are brutal killers:

What has happened to you? /First/it was the gun /now/it is beauty.

Shashi Shekhar Toshkhani has written a complete reflection of the book and the translation. I, personally, as a reviewer, take courage to second his comment that the translator, Arvind Gigoo, has translated not just Hindi language into English language but Hindi poetry into English poetry. This sentence is a complete analysis and a right compliment. The translator is all in one and one in all.

After twenty-five years of displacement, the reading out of the translation of the poems which are wholly confined to the same wavelength since 1990, when the exodus happened, becomes droning. Protest being the genuine right of the poets and the writers but the repetitive continuity of the content of ‘exile’ which has been already and widely published loses worth.

Trending Now

E-Paper